You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

An Age of Miracles III: The Romans Endure

- Thread starter Basileus444

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 52 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Rhomania's General Crisis, Part 17.2: Sustaining the War, Part 3 March Updates on Hiatus Rhomania's General Crisis, Part 17.3: Sustaining the War, Part 4 Rhomania's General Crisis, Part 17.4: Sustaining the War, Part 5 Rhomania's General Crisis, Part 18.0: Shall the Sword Devour Forever? Part 1 Rhomania's General Crisis, Part 18.1: Shall the Sword Devour Forever? Part 2 Rhomania's General Crisis, Part 18.2: Shall the Sword Devour Forever? Part 3 Rhomania's General Crisis, Part 19.0: Go Forward, Part 1About what ? economy, population growth, the gold rush, sugar production, immigration. Current geography of the colony and differences with OTL Brazil?In regard to sources on Brazil I'm beat someone will have to help me out. Most of what I know about it is either recent history or snippets from school history classes which mainly focused on Spanish speaking Latin America

Arabic and Mozarabic in the Muslim part of the colony, Spanish, Portuguese and local dialects in the south, together with Tupinambá (local language). At otl brasil, the colony only really began to speak Portuguese in 1759, through the Directory Law: it made the use of Portuguese the official language mandatory throughout the national territory. Until that period, Brazil had two languages: the general language or Tupinambá and Portuguese.I'd imagine this would be even more confusing in Brazil where the colonies predate Spain so they'd definitely be speaking mozarabic and portugese aside from whatever "Spanish" the motherland has cooked up

Hey @SB4 (I kind of summarized the story but there will always be something missing, any questions just ask)

The colonial period of otl brasil can be divided into different economic cycles (which in turn influence the population).

The first economic activity of the colony was the exploration of brazilwood, but it lost its importance when the trees began to become scarce in the Atlantic Forest region (the wood and the sap of the tree were used by the Europeans in the manufacture of furniture and in the dyeing of fabrics.)

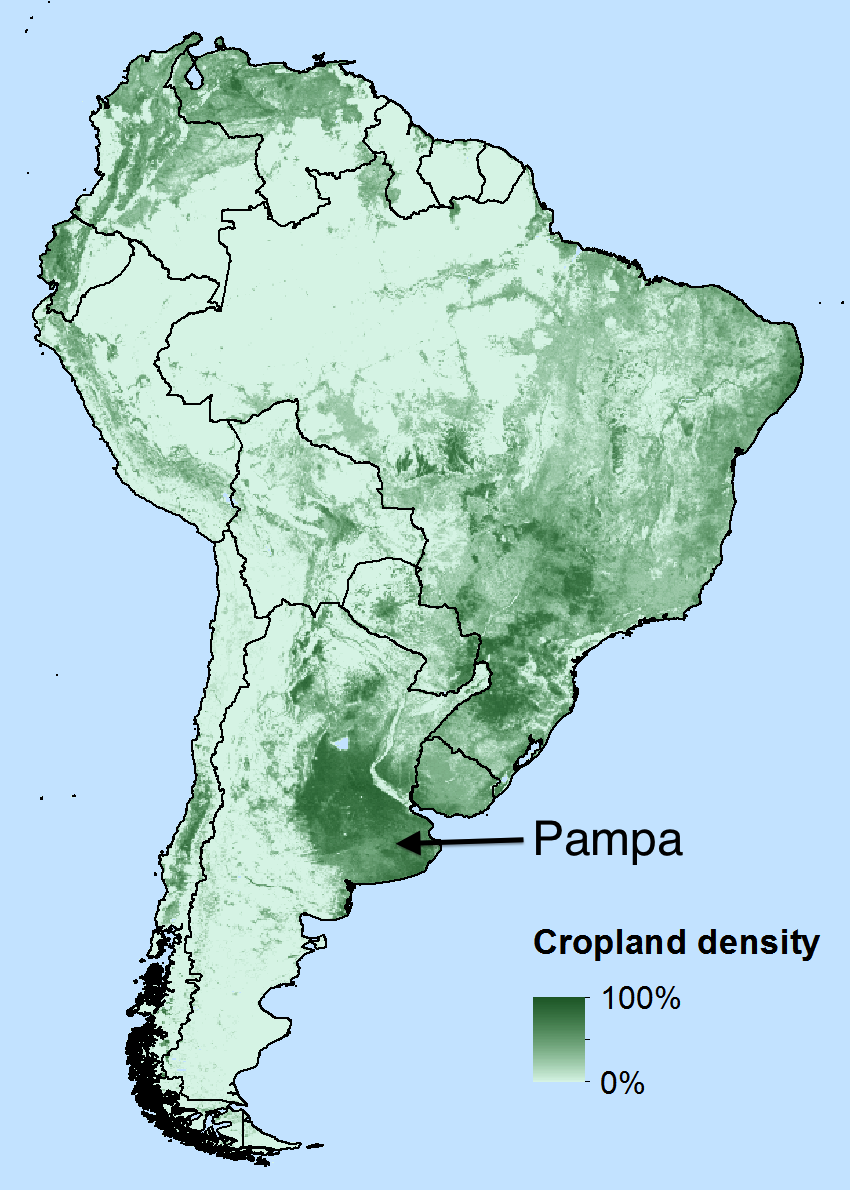

After that, the boom in monocultures followed by monocultures exporting sugar cane, cotton and tobacco . At the same time, cattle raising, seen as a means of subsistence, contributes to the colonization of the interior of the country (ITTL, cattle production and subsistence agriculture will be much, much greater due to the complete control of the pampas by the colony.). in OTL there was a sugar crisis in the Portuguese colonial period due to the Dutch who were expelled from Pernambuco (brazil) that learn the techniques in their period in the colony and began to plant sugar cane in the Antilles, their colony in Central America, and soon became competitors of Brazilian sugar. This caused the price of sugar production made in Brazil to devalue. This does not occur in this timeline making the sugar boom last much longer (even with the problems, brazil continued to be the largest producer of sugar in the otl).

Then we have the gold rush at otl started in 1690, when bandeirantes discovered large gold deposits in the mountains of Minas Gerais . With that more than 400,000 Portuguese and 500,000 African slaves came to the gold region to mine. Many people abandoned the sugar plantations and towns in the northeast coast to go to the gold region. By 1725, half the population of Brazil was living in southeastern Brazil. Portugal in 1700 had a population of 2 M. This means that +-20% of the portuguese population immigrated to brazil during the gold rush. The country had to put quotas on immigration so that the majority of its population did not immigrate to Brazil. the Brazilian Gold Rush created the world's longest gold rush period and the largest gold mines in South America, besides being the biggest diamond producer for 2 centuries if I'm not mistaken.

Below is an image of Brazil's economic evolution at OTL for three centuries

16th Century: Sugar cane, Livestock and brazilwood

17th Century : Sugar cane, Mining, Livestock and Drugs from the Sertão

18th Century : Sugarcane, Mining, Livestock, Drugs from the Sertão and Cotton.

At the beginning of the 16th century, Brazil had 45 thousand people in the colony, at the beginning of the 17th century it had 300.00 and finally at the beginning of the 18th century it had 3.6 million inhabitants (a growth of 12X. 630 thousand more than the metropolis) . Due to the fact that Portugal (Spain) in this timeline is the union of Castile, Portugal and Andalus, the population will be much larger. I don't know the population of Spain from TTl but this will be very impactful. This can already be seen with the size of the colony when compared to otl brasil.

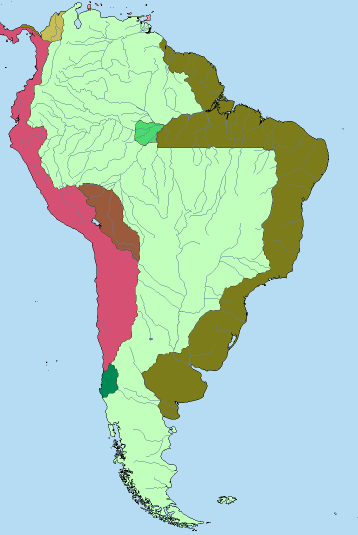

OTL Brazil TTL Brazil

VS

VS

The colony also has control of the Plata basin (the most important in South America) and the Amazon basin (second most important) together with the pamaps region which is ridiculously fertile. As a whole, the Muslim part of the colony will be around the Amazon basin and the Christian part in the Plata basin. With the control of the entire temperate and semi-temperate region of South America by a single colony, there will be a much greater immigration of Europeans.

The colonial period of otl brasil can be divided into different economic cycles (which in turn influence the population).

The first economic activity of the colony was the exploration of brazilwood, but it lost its importance when the trees began to become scarce in the Atlantic Forest region (the wood and the sap of the tree were used by the Europeans in the manufacture of furniture and in the dyeing of fabrics.)

After that, the boom in monocultures followed by monocultures exporting sugar cane, cotton and tobacco . At the same time, cattle raising, seen as a means of subsistence, contributes to the colonization of the interior of the country (ITTL, cattle production and subsistence agriculture will be much, much greater due to the complete control of the pampas by the colony.). in OTL there was a sugar crisis in the Portuguese colonial period due to the Dutch who were expelled from Pernambuco (brazil) that learn the techniques in their period in the colony and began to plant sugar cane in the Antilles, their colony in Central America, and soon became competitors of Brazilian sugar. This caused the price of sugar production made in Brazil to devalue. This does not occur in this timeline making the sugar boom last much longer (even with the problems, brazil continued to be the largest producer of sugar in the otl).

Then we have the gold rush at otl started in 1690, when bandeirantes discovered large gold deposits in the mountains of Minas Gerais . With that more than 400,000 Portuguese and 500,000 African slaves came to the gold region to mine. Many people abandoned the sugar plantations and towns in the northeast coast to go to the gold region. By 1725, half the population of Brazil was living in southeastern Brazil. Portugal in 1700 had a population of 2 M. This means that +-20% of the portuguese population immigrated to brazil during the gold rush. The country had to put quotas on immigration so that the majority of its population did not immigrate to Brazil. the Brazilian Gold Rush created the world's longest gold rush period and the largest gold mines in South America, besides being the biggest diamond producer for 2 centuries if I'm not mistaken.

Below is an image of Brazil's economic evolution at OTL for three centuries

16th Century: Sugar cane, Livestock and brazilwood

17th Century : Sugar cane, Mining, Livestock and Drugs from the Sertão

18th Century : Sugarcane, Mining, Livestock, Drugs from the Sertão and Cotton.

At the beginning of the 16th century, Brazil had 45 thousand people in the colony, at the beginning of the 17th century it had 300.00 and finally at the beginning of the 18th century it had 3.6 million inhabitants (a growth of 12X. 630 thousand more than the metropolis) . Due to the fact that Portugal (Spain) in this timeline is the union of Castile, Portugal and Andalus, the population will be much larger. I don't know the population of Spain from TTl but this will be very impactful. This can already be seen with the size of the colony when compared to otl brasil.

OTL Brazil TTL Brazil

The colony also has control of the Plata basin (the most important in South America) and the Amazon basin (second most important) together with the pamaps region which is ridiculously fertile. As a whole, the Muslim part of the colony will be around the Amazon basin and the Christian part in the Plata basin. With the control of the entire temperate and semi-temperate region of South America by a single colony, there will be a much greater immigration of Europeans.

Last edited:

Thank you @holycookie interesting reading. Yeah Brazil ttl has all the tools to become a major power long term especially now it has a greater population base to draw on in castille and andalusia. Plus control of the plata basin to provide for agriculture

Not quite yet. Not until industrial equipment allows for the Brazilians to bypass the Great Escarpment entirely and blast a connection into existence between the Amazon's major transport arteries and those of the Plata. Otherwise they'll effectively have to split their economy in half--Amazon goes north, Plata stays in the south. And it's stupidly difficult to get sufficient overland coastal traffic from north to south in Brazil anyways, so either they try and knock down a half-dozen mountains or be forced send like 80% of their shit down the Paraguay River. Given the map you posted, somebody's gonna have to spend half a century, if not longer, building roads and canals between the Sao Francisco, Guapore, Paraguay, Xingu, and Madeira rivers in order to actually get shit done.Thank you @holycookie interesting reading. Yeah Brazil ttl has all the tools to become a major power long term especially now it has a greater population base to draw on in castille and andalusia. Plus control of the plata basin to provide for agriculture

Rhomania's General Crisis, Part 5.2: Shooting at Target

While I do reserve the right to change my mind, this plan is that this war is the final Roman-Persian War. They've been near-constant since the beginning of the century, and have been a thing since Crassus was alive, so I think the concept could use a break. That doesn't mean there won't be diplomatic incidents and maybe the odd war scare, but active hostilities won't be a thing after this.

After finishing up its usual autumnal exercises, the Armeniakon tagma does not disperse to its various winter quarters as usual. The bulk heads southeast to Mepsila (Mosul) where its forces are bolstered by various kastron soldiers. After drawing on supplies from the garrison storehouses, the 11,700 strong expedition crosses the frontier.

Surprise isn’t completely total, but close to it. Ottoman spies had noticed the unusual behavior of the Armeniakon tagma after its exercises, as well as small mustering units of reserve kastron forces to forward Roman outposts. But their reports do not precede the invasion by much, and even that potential warning is largely wasted. Launching a Mesopotamian offensive with what is essentially a single reinforced tagma is entirely unprecedented in Roman strategy, so these signals do not register with Ottoman officials.

Another way surprise is upheld is that no formal declaration of war is issued by the Romans until October 5, by which point the Roman expedition is on the frontier. Roman accounts claim they did not cross until after the declaration; Persian ones claim the opposite. Either way, it is not possible for the Roman ambassador in Baghdad to communicate with Strategos Keraunos. His instructions are to deliver the declaration on the morning of October 5; he does not know where the Armeniakon tagma is at that point.

All wars need a justification and the Roman ambassador cites alleged Mesopotamian inability or refusal to control its nomads, who then violate Roman territory. The Romans are thus intervening defensively to secure the area, given Baghdad’s incapacity. This is referring to the frequent nomadic traffic that crosses the frontiers of both empires, as the pastoralists care nothing for such political boundaries; they are focusing on maintaining their herds and shifting from winter to summer pastures and vice versa. Nomads from all sides, Roman, Mesopotamian, Persian, and Georgian (farther east) do this.

There are sometimes feuds and skirmishes, either between various nomad bands or with settled communities. The reasons vary such as from blood feuds or disputes over rights-of-way, but are local in origin and oftentimes nothing more than the commonplace frictions between the nomad and the sown. There is nothing inherently political about any of it, and it has been going on in some form since classical Romans arrived in the east. Only the details have changed. Nor has it gotten particularly more severe of late. In 1660, more Romans were killed because of feuds between Albanian clans than because of this nomadic traffic.

There is more to the ambassador’s message than just this rather paltry diplomatic fig leaf. The ruler of Mesopotamia is Alexandros of Baghdad, the eldest child of Andreas III and Maria of Agra. Out of recognition for his distinguished ancestry, if he surrenders Mesopotamia without a struggle, he will be granted large landholdings in Rhomania and freedom of movement within the Empire. The grants are quite substantial and would make Alexandros one of the greatest private landowners within the Empire. Smaller but still significant offerings are also promised to his mother Maria and his younger brother Nikephoros, who is commander of the Mesopotamian army.

One possible explanation of the offer is that having the children, albeit illegitimate, of Andreas III around would be one way to keep Herakleios III in line, or to act as a possible replacement. The other, and likely more significant, is that this is part of the strategy to take Mesopotamia out quickly, as Mesopotamia is not the real fight. Persia is.

Topkapi Palace, Baghdad, October 5, 1660:

Alexandros’s chin itched, right at the tip where his brown beard had decided to skip gray and grow a streak of white instead. He clenched his fist, his nails biting into his palms, as he resisted the urge to scratch. It also helped him resist a much stronger urge, which involved a blunt heavy object and the face of the Roman ambassador.

The Roman ambassador, Ioannes Barykephalos, had requested a public audience over two weeks ago, for this specific morning, after receiving a sealed mail packet from Rhomania. That had been a little unusual. Normally such things were scheduled for earliest convenience, rather than a specific date, and a normal ambassador did not get to dictate a normal king’s schedule. The king decided when, or if, he’d receive an ambassador, not the other way around.

But these were not normal circumstances. Although both the Roman and Persian envoys were styled as ambassadors, as if they were posted to a sovereign state, and made requests to his court, Alexandros knew he could not refuse such requests, no matter how irregular. His subservience was made quite clear in the annual ceremony where he signed off half his annual income to the ambassadors, evenly split between them, to send to their governments.

It was somewhat less grating with the Persians. This was Mesopotamia, the old Ottoman heartland, where Osman I, Osman the Great, and his followers had carved out a state for themselves from the fragments of the Il-Khanate. Iskandar, as heir of Osman, had claim to these lands. But Herakleios III had none in Alexandros’s opinion, and there was also his personal grievance with the House of Sideros.

Ioannes had ceased speaking and was now looking at Alexandros, awaiting his response. For a moment Alexandros ignored him, his eyes sweeping across the ranks of courtiers and officials. This was a full court ceremony with everyone in audience. The looks on their faces varied. Some were impassive, not showing what they felt. Those less controlled, or less willing to dissemble, showed a mixture of fear and anger, the proportion varying. Certainly no one looked happy. Alexandros couldn’t look on the face of his mother. She was present, but was behind a screen that hid her from view, in a corner behind him and to his left. This was her usual custom, allowing her to know things and give counsel, but without being too obtrusive and upsetting delicate sensibilities.

He was struggling to think of a polite and diplomatic response when he heard a faint warble and then a long thin whistle come from the screen. It was his mother, signaling him in the aural code they shared along with his little brother Nikephoros. Alexandros looked at Nikephoros, standing next to him at his right hand. Their eyes met, Nikephoros’s glinting, a faint smile on his lips. He too had heard the signal, too faint to be heard by anyone else.

Alexandros looked at the ambassador. “Your master is a liar,” he replied. “And a very bad one at that.” There was a murmur of surprise in the crowd; Ioannes’s expression was blank. “He condemns us for crimes of which he is equally guilty, and he has many crimes unique to himself besides that.

“He offers us great gifts if we should yield to his unrighteous greed, yet why should we believe him? Your master sits upon the throne of our father, enjoying a birthright his family usurped from ours. Your master’s father sought to give us this realm as compensation for that crime, and yet your master, demonstrating not only rampant greed but utter disrespect for the wishes of his own father, seeks to take this realm from us. Doubtless, based on such patterns, in the future he would then seize those gifts you say he will grant now for our obedience, justifying it on claims that have no basis in truth or justice. Your master is a liar and a would-be thief, whose words are false and promises empty.”

“It is regrettable that you feel such emotional grievances against his august majesty, Emperor Herakleios III,” Ioannes replied. “My master has always been a good friend to your Highness and the realm of Mesopotamia. He wishes merely to ensure yours and its wellbeing, its prosperity and security. He offers to take a most heavy burden from yourself and offers great gifts in exchange. Such is the act of a true friend. Surely, your Highness must see that.”

“If your master wishes to show himself a good friend to ourselves and to the people of Mesopotamia, he can easily prove it. He may take his army with which he threatens us with death and destruction and send it back to where it belongs, in his own realm. As for this burden, we neither require nor desire his assistance. His gifts he may keep. We have no need for them, only for him to leave us alone and to abide by the wishes of his father.”

“It is regrettable that you feel that way,” Ioannes said. “But if you do not trust the goodwill of my master, surely you recognize his power, of his vast superiority in arms to your own? Would it not be wiser to submit now, before all the terror and suffering of a hopeless war?”

“The future is never so certain for there to be no hope, and to purchase peace at the price of slavery is a most poor bargain. God alone, the Supreme Judge, upholder of righteousness and truth, the Humbler of the proud, knows the future. He will decide the outcome of the war. We put our trust in him, not in your worthless master.”

Ioannes opened his mouth. “Speak no more,” Alexandros said. “We are weary of this audience and of you. The time for talk is over. You have two hours to vacate the city. If you remain past that time, you will be the first Roman to die for the sake of your master’s greed, but not the last.”

Riders go out from Baghdad. Some head north, one of them the Roman ambassador and his entourage. Others head south and west, rallying Mesopotamians to the banners, seeking to gather up recruits and weapons and supplies. Still more head east to the court of the Shahanshah, to ask Iskandar to honor the oath he’d made to uphold the legacy of his blood brother, and to bring the might of Persia onto the scales.

To the north, the Armeniakon tagma blasts through the frontier with barely any opposition, but it is soon made clear it will not always be such smooth sailing. The people here have much experience of Roman attacks; their cemeteries attest to that. And the last fruit of Roman military action they had seen were the remnants of the Great Crime, making the stakes absolutely clear in their minds. To this day, no one is sure which village issued the famous response. But one, when summoned to surrender by a Roman cavalry unit, replied “it is plain you wish to exterminate us, and we do not wish to be exterminated.”

During the OTL 1500s, after the initial Portuguese surge, the new Cape and old Mediterranean trade routes ended up splitting the eastern trade between them. It wasn't until the 1600s and the arrival of the English, French, and especially Dutch in force where the Cape route began to consistently dominate. ITTL, we're seeing more akin to the OTL 1500s situation, where the shift northward, while still present, is weaker.OTL saw the balance of trade move from the Mediterranean to the North Sea in the early modern era. I still believe that will happen ITLL, though ITTL we see something that did not happen, a pretty cohesive Med. I dont see why a much richer Med wouldnt happen, including North Africa.

* * *

Rhomania’s General Crisis, part 5.2-Shooting at Target:

Rhomania’s General Crisis, part 5.2-Shooting at Target:

After finishing up its usual autumnal exercises, the Armeniakon tagma does not disperse to its various winter quarters as usual. The bulk heads southeast to Mepsila (Mosul) where its forces are bolstered by various kastron soldiers. After drawing on supplies from the garrison storehouses, the 11,700 strong expedition crosses the frontier.

Surprise isn’t completely total, but close to it. Ottoman spies had noticed the unusual behavior of the Armeniakon tagma after its exercises, as well as small mustering units of reserve kastron forces to forward Roman outposts. But their reports do not precede the invasion by much, and even that potential warning is largely wasted. Launching a Mesopotamian offensive with what is essentially a single reinforced tagma is entirely unprecedented in Roman strategy, so these signals do not register with Ottoman officials.

Another way surprise is upheld is that no formal declaration of war is issued by the Romans until October 5, by which point the Roman expedition is on the frontier. Roman accounts claim they did not cross until after the declaration; Persian ones claim the opposite. Either way, it is not possible for the Roman ambassador in Baghdad to communicate with Strategos Keraunos. His instructions are to deliver the declaration on the morning of October 5; he does not know where the Armeniakon tagma is at that point.

All wars need a justification and the Roman ambassador cites alleged Mesopotamian inability or refusal to control its nomads, who then violate Roman territory. The Romans are thus intervening defensively to secure the area, given Baghdad’s incapacity. This is referring to the frequent nomadic traffic that crosses the frontiers of both empires, as the pastoralists care nothing for such political boundaries; they are focusing on maintaining their herds and shifting from winter to summer pastures and vice versa. Nomads from all sides, Roman, Mesopotamian, Persian, and Georgian (farther east) do this.

There are sometimes feuds and skirmishes, either between various nomad bands or with settled communities. The reasons vary such as from blood feuds or disputes over rights-of-way, but are local in origin and oftentimes nothing more than the commonplace frictions between the nomad and the sown. There is nothing inherently political about any of it, and it has been going on in some form since classical Romans arrived in the east. Only the details have changed. Nor has it gotten particularly more severe of late. In 1660, more Romans were killed because of feuds between Albanian clans than because of this nomadic traffic.

There is more to the ambassador’s message than just this rather paltry diplomatic fig leaf. The ruler of Mesopotamia is Alexandros of Baghdad, the eldest child of Andreas III and Maria of Agra. Out of recognition for his distinguished ancestry, if he surrenders Mesopotamia without a struggle, he will be granted large landholdings in Rhomania and freedom of movement within the Empire. The grants are quite substantial and would make Alexandros one of the greatest private landowners within the Empire. Smaller but still significant offerings are also promised to his mother Maria and his younger brother Nikephoros, who is commander of the Mesopotamian army.

One possible explanation of the offer is that having the children, albeit illegitimate, of Andreas III around would be one way to keep Herakleios III in line, or to act as a possible replacement. The other, and likely more significant, is that this is part of the strategy to take Mesopotamia out quickly, as Mesopotamia is not the real fight. Persia is.

* * *

Topkapi Palace, Baghdad, October 5, 1660:

Alexandros’s chin itched, right at the tip where his brown beard had decided to skip gray and grow a streak of white instead. He clenched his fist, his nails biting into his palms, as he resisted the urge to scratch. It also helped him resist a much stronger urge, which involved a blunt heavy object and the face of the Roman ambassador.

The Roman ambassador, Ioannes Barykephalos, had requested a public audience over two weeks ago, for this specific morning, after receiving a sealed mail packet from Rhomania. That had been a little unusual. Normally such things were scheduled for earliest convenience, rather than a specific date, and a normal ambassador did not get to dictate a normal king’s schedule. The king decided when, or if, he’d receive an ambassador, not the other way around.

But these were not normal circumstances. Although both the Roman and Persian envoys were styled as ambassadors, as if they were posted to a sovereign state, and made requests to his court, Alexandros knew he could not refuse such requests, no matter how irregular. His subservience was made quite clear in the annual ceremony where he signed off half his annual income to the ambassadors, evenly split between them, to send to their governments.

It was somewhat less grating with the Persians. This was Mesopotamia, the old Ottoman heartland, where Osman I, Osman the Great, and his followers had carved out a state for themselves from the fragments of the Il-Khanate. Iskandar, as heir of Osman, had claim to these lands. But Herakleios III had none in Alexandros’s opinion, and there was also his personal grievance with the House of Sideros.

Ioannes had ceased speaking and was now looking at Alexandros, awaiting his response. For a moment Alexandros ignored him, his eyes sweeping across the ranks of courtiers and officials. This was a full court ceremony with everyone in audience. The looks on their faces varied. Some were impassive, not showing what they felt. Those less controlled, or less willing to dissemble, showed a mixture of fear and anger, the proportion varying. Certainly no one looked happy. Alexandros couldn’t look on the face of his mother. She was present, but was behind a screen that hid her from view, in a corner behind him and to his left. This was her usual custom, allowing her to know things and give counsel, but without being too obtrusive and upsetting delicate sensibilities.

He was struggling to think of a polite and diplomatic response when he heard a faint warble and then a long thin whistle come from the screen. It was his mother, signaling him in the aural code they shared along with his little brother Nikephoros. Alexandros looked at Nikephoros, standing next to him at his right hand. Their eyes met, Nikephoros’s glinting, a faint smile on his lips. He too had heard the signal, too faint to be heard by anyone else.

Alexandros looked at the ambassador. “Your master is a liar,” he replied. “And a very bad one at that.” There was a murmur of surprise in the crowd; Ioannes’s expression was blank. “He condemns us for crimes of which he is equally guilty, and he has many crimes unique to himself besides that.

“He offers us great gifts if we should yield to his unrighteous greed, yet why should we believe him? Your master sits upon the throne of our father, enjoying a birthright his family usurped from ours. Your master’s father sought to give us this realm as compensation for that crime, and yet your master, demonstrating not only rampant greed but utter disrespect for the wishes of his own father, seeks to take this realm from us. Doubtless, based on such patterns, in the future he would then seize those gifts you say he will grant now for our obedience, justifying it on claims that have no basis in truth or justice. Your master is a liar and a would-be thief, whose words are false and promises empty.”

“It is regrettable that you feel such emotional grievances against his august majesty, Emperor Herakleios III,” Ioannes replied. “My master has always been a good friend to your Highness and the realm of Mesopotamia. He wishes merely to ensure yours and its wellbeing, its prosperity and security. He offers to take a most heavy burden from yourself and offers great gifts in exchange. Such is the act of a true friend. Surely, your Highness must see that.”

“If your master wishes to show himself a good friend to ourselves and to the people of Mesopotamia, he can easily prove it. He may take his army with which he threatens us with death and destruction and send it back to where it belongs, in his own realm. As for this burden, we neither require nor desire his assistance. His gifts he may keep. We have no need for them, only for him to leave us alone and to abide by the wishes of his father.”

“It is regrettable that you feel that way,” Ioannes said. “But if you do not trust the goodwill of my master, surely you recognize his power, of his vast superiority in arms to your own? Would it not be wiser to submit now, before all the terror and suffering of a hopeless war?”

“The future is never so certain for there to be no hope, and to purchase peace at the price of slavery is a most poor bargain. God alone, the Supreme Judge, upholder of righteousness and truth, the Humbler of the proud, knows the future. He will decide the outcome of the war. We put our trust in him, not in your worthless master.”

Ioannes opened his mouth. “Speak no more,” Alexandros said. “We are weary of this audience and of you. The time for talk is over. You have two hours to vacate the city. If you remain past that time, you will be the first Roman to die for the sake of your master’s greed, but not the last.”

* * *

Riders go out from Baghdad. Some head north, one of them the Roman ambassador and his entourage. Others head south and west, rallying Mesopotamians to the banners, seeking to gather up recruits and weapons and supplies. Still more head east to the court of the Shahanshah, to ask Iskandar to honor the oath he’d made to uphold the legacy of his blood brother, and to bring the might of Persia onto the scales.

To the north, the Armeniakon tagma blasts through the frontier with barely any opposition, but it is soon made clear it will not always be such smooth sailing. The people here have much experience of Roman attacks; their cemeteries attest to that. And the last fruit of Roman military action they had seen were the remnants of the Great Crime, making the stakes absolutely clear in their minds. To this day, no one is sure which village issued the famous response. But one, when summoned to surrender by a Roman cavalry unit, replied “it is plain you wish to exterminate us, and we do not wish to be exterminated.”

Even if the Mesopotamians folded like a wer tissue at the border, that wouldn’t be enough to siege Baghdad would it?After drawing on supplies from the garrison storehouses, the 11,700 strong expedition crosses the frontier.

Also interesting to see that the bastards see the Roman throne as theirs, they view themselves as legitimate?

It could precipitate the Tourmarchs wiping them out if they end up capturing them.Interesting to see that the bastards see the Roman throne as theirs, they view themselves as legitimate?

What could be a twist is the silent majority siding with Iskander and him putting Heraklios' brother on the throne. I can imagine there are many that are not pleased with the military cabal, and would welcome a competent Sideros on the throne. The historical irony too would be cinnamon spread delicious.

I wonder what the actual official name/what they call themselves of the ottoman empire is? Sublime ottoman state like otl? Or a version of Eranshahr? Maybe empire of the Iranians and Turks. With the effective persification of the empire AND change of ruling family (although still related to osman if I remember correctly) the latter might fit more

Question: with the Persians being the sole supporter of the Mesopotamian right now and the fact their population are mostly Muslims, wouldnt it be wiser for them to convert?

Evilprodigy

Donor

The Ottomans were pretty well 'persified' iotl too as a heritage of the Seljuk Sultanate. The courts, ruling class, and royal household spoke the Persian language, used Persian writing for bureaucracy, made Persian style art, and told Persian stories or poetry. The otl terminology thus already has Persian connotations and even then the change of ruler would more likely mean a desire to demonstrate continuity with the rest of the dynasty to portray themselves as a rightful ruler. Changing things like names goes against that perception so I don't think they would have any reason to change it. Turkish control in this part of the world over culturally Persian peoples has been the rule for the better part of seven hundred years starting with the Ghaznavids.I wonder what the actual official name/what they call themselves of the ottoman empire is? Sublime ottoman state like otl? Or a version of Eranshahr? Maybe empire of the Iranians and Turks. With the effective persification of the empire AND change of ruling family (although still related to osman if I remember correctly) the latter might fit more

You could say this about a great deal of historic polities who never converted to the faith of their subjects but did just fine.Question: with the Persians being the sole supporter of the Mesopotamian right now and the fact their population are mostly Muslims, wouldnt it be wiser for them to convert?

you know it would be funny if this war would be the cause of the current dynasty of rhomania to be overthrownWhile I do reserve the right to change my mind, this plan is that this war is the final Roman-Persian War. They've been near-constant since the beginning of the century, and have been a thing since Crassus was alive, so I think the concept could use a break. That doesn't mean there won't be diplomatic incidents and maybe the odd war scare, but active hostilities won't be a thing after this.

During the OTL 1500s, after the initial Portuguese surge, the new Cape and old Mediterranean trade routes ended up splitting the eastern trade between them. It wasn't until the 1600s and the arrival of the English, French, and especially Dutch in force where the Cape route began to consistently dominate. ITTL, we're seeing more akin to the OTL 1500s situation, where the shift northward, while still present, is weaker.

* * *

Rhomania’s General Crisis, part 5.2-Shooting at Target:

After finishing up its usual autumnal exercises, the Armeniakon tagma does not disperse to its various winter quarters as usual. The bulk heads southeast to Mepsila (Mosul) where its forces are bolstered by various kastron soldiers. After drawing on supplies from the garrison storehouses, the 11,700 strong expedition crosses the frontier.

Surprise isn’t completely total, but close to it. Ottoman spies had noticed the unusual behavior of the Armeniakon tagma after its exercises, as well as small mustering units of reserve kastron forces to forward Roman outposts. But their reports do not precede the invasion by much, and even that potential warning is largely wasted. Launching a Mesopotamian offensive with what is essentially a single reinforced tagma is entirely unprecedented in Roman strategy, so these signals do not register with Ottoman officials.

Another way surprise is upheld is that no formal declaration of war is issued by the Romans until October 5, by which point the Roman expedition is on the frontier. Roman accounts claim they did not cross until after the declaration; Persian ones claim the opposite. Either way, it is not possible for the Roman ambassador in Baghdad to communicate with Strategos Keraunos. His instructions are to deliver the declaration on the morning of October 5; he does not know where the Armeniakon tagma is at that point.

All wars need a justification and the Roman ambassador cites alleged Mesopotamian inability or refusal to control its nomads, who then violate Roman territory. The Romans are thus intervening defensively to secure the area, given Baghdad’s incapacity. This is referring to the frequent nomadic traffic that crosses the frontiers of both empires, as the pastoralists care nothing for such political boundaries; they are focusing on maintaining their herds and shifting from winter to summer pastures and vice versa. Nomads from all sides, Roman, Mesopotamian, Persian, and Georgian (farther east) do this.

There are sometimes feuds and skirmishes, either between various nomad bands or with settled communities. The reasons vary such as from blood feuds or disputes over rights-of-way, but are local in origin and oftentimes nothing more than the commonplace frictions between the nomad and the sown. There is nothing inherently political about any of it, and it has been going on in some form since classical Romans arrived in the east. Only the details have changed. Nor has it gotten particularly more severe of late. In 1660, more Romans were killed because of feuds between Albanian clans than because of this nomadic traffic.

There is more to the ambassador’s message than just this rather paltry diplomatic fig leaf. The ruler of Mesopotamia is Alexandros of Baghdad, the eldest child of Andreas III and Maria of Agra. Out of recognition for his distinguished ancestry, if he surrenders Mesopotamia without a struggle, he will be granted large landholdings in Rhomania and freedom of movement within the Empire. The grants are quite substantial and would make Alexandros one of the greatest private landowners within the Empire. Smaller but still significant offerings are also promised to his mother Maria and his younger brother Nikephoros, who is commander of the Mesopotamian army.

One possible explanation of the offer is that having the children, albeit illegitimate, of Andreas III around would be one way to keep Herakleios III in line, or to act as a possible replacement. The other, and likely more significant, is that this is part of the strategy to take Mesopotamia out quickly, as Mesopotamia is not the real fight. Persia is.

* * *

Topkapi Palace, Baghdad, October 5, 1660:

Alexandros’s chin itched, right at the tip where his brown beard had decided to skip gray and grow a streak of white instead. He clenched his fist, his nails biting into his palms, as he resisted the urge to scratch. It also helped him resist a much stronger urge, which involved a blunt heavy object and the face of the Roman ambassador.

The Roman ambassador, Ioannes Barykephalos, had requested a public audience over two weeks ago, for this specific morning, after receiving a sealed mail packet from Rhomania. That had been a little unusual. Normally such things were scheduled for earliest convenience, rather than a specific date, and a normal ambassador did not get to dictate a normal king’s schedule. The king decided when, or if, he’d receive an ambassador, not the other way around.

But these were not normal circumstances. Although both the Roman and Persian envoys were styled as ambassadors, as if they were posted to a sovereign state, and made requests to his court, Alexandros knew he could not refuse such requests, no matter how irregular. His subservience was made quite clear in the annual ceremony where he signed off half his annual income to the ambassadors, evenly split between them, to send to their governments.

It was somewhat less grating with the Persians. This was Mesopotamia, the old Ottoman heartland, where Osman I, Osman the Great, and his followers had carved out a state for themselves from the fragments of the Il-Khanate. Iskandar, as heir of Osman, had claim to these lands. But Herakleios III had none in Alexandros’s opinion, and there was also his personal grievance with the House of Sideros.

Ioannes had ceased speaking and was now looking at Alexandros, awaiting his response. For a moment Alexandros ignored him, his eyes sweeping across the ranks of courtiers and officials. This was a full court ceremony with everyone in audience. The looks on their faces varied. Some were impassive, not showing what they felt. Those less controlled, or less willing to dissemble, showed a mixture of fear and anger, the proportion varying. Certainly no one looked happy. Alexandros couldn’t look on the face of his mother. She was present, but was behind a screen that hid her from view, in a corner behind him and to his left. This was her usual custom, allowing her to know things and give counsel, but without being too obtrusive and upsetting delicate sensibilities.

He was struggling to think of a polite and diplomatic response when he heard a faint warble and then a long thin whistle come from the screen. It was his mother, signaling him in the aural code they shared along with his little brother Nikephoros. Alexandros looked at Nikephoros, standing next to him at his right hand. Their eyes met, Nikephoros’s glinting, a faint smile on his lips. He too had heard the signal, too faint to be heard by anyone else.

Alexandros looked at the ambassador. “Your master is a liar,” he replied. “And a very bad one at that.” There was a murmur of surprise in the crowd; Ioannes’s expression was blank. “He condemns us for crimes of which he is equally guilty, and he has many crimes unique to himself besides that.

“He offers us great gifts if we should yield to his unrighteous greed, yet why should we believe him? Your master sits upon the throne of our father, enjoying a birthright his family usurped from ours. Your master’s father sought to give us this realm as compensation for that crime, and yet your master, demonstrating not only rampant greed but utter disrespect for the wishes of his own father, seeks to take this realm from us. Doubtless, based on such patterns, in the future he would then seize those gifts you say he will grant now for our obedience, justifying it on claims that have no basis in truth or justice. Your master is a liar and a would-be thief, whose words are false and promises empty.”

“It is regrettable that you feel such emotional grievances against his august majesty, Emperor Herakleios III,” Ioannes replied. “My master has always been a good friend to your Highness and the realm of Mesopotamia. He wishes merely to ensure yours and its wellbeing, its prosperity and security. He offers to take a most heavy burden from yourself and offers great gifts in exchange. Such is the act of a true friend. Surely, your Highness must see that.”

“If your master wishes to show himself a good friend to ourselves and to the people of Mesopotamia, he can easily prove it. He may take his army with which he threatens us with death and destruction and send it back to where it belongs, in his own realm. As for this burden, we neither require nor desire his assistance. His gifts he may keep. We have no need for them, only for him to leave us alone and to abide by the wishes of his father.”

“It is regrettable that you feel that way,” Ioannes said. “But if you do not trust the goodwill of my master, surely you recognize his power, of his vast superiority in arms to your own? Would it not be wiser to submit now, before all the terror and suffering of a hopeless war?”

“The future is never so certain for there to be no hope, and to purchase peace at the price of slavery is a most poor bargain. God alone, the Supreme Judge, upholder of righteousness and truth, the Humbler of the proud, knows the future. He will decide the outcome of the war. We put our trust in him, not in your worthless master.”

Ioannes opened his mouth. “Speak no more,” Alexandros said. “We are weary of this audience and of you. The time for talk is over. You have two hours to vacate the city. If you remain past that time, you will be the first Roman to die for the sake of your master’s greed, but not the last.”

* * *

Riders go out from Baghdad. Some head north, one of them the Roman ambassador and his entourage. Others head south and west, rallying Mesopotamians to the banners, seeking to gather up recruits and weapons and supplies. Still more head east to the court of the Shahanshah, to ask Iskandar to honor the oath he’d made to uphold the legacy of his blood brother, and to bring the might of Persia onto the scales.

To the north, the Armeniakon tagma blasts through the frontier with barely any opposition, but it is soon made clear it will not always be such smooth sailing. The people here have much experience of Roman attacks; their cemeteries attest to that. And the last fruit of Roman military action they had seen were the remnants of the Great Crime, making the stakes absolutely clear in their minds. To this day, no one is sure which village issued the famous response. But one, when summoned to surrender by a Roman cavalry unit, replied “it is plain you wish to exterminate us, and we do not wish to be exterminated.”

I mean even if he is a bastard his family history to the Rhomanian throne is much deeper than the current monarchEven if the Mesopotamians folded like a wer tissue at the border, that wouldn’t be enough to siege Baghdad would it?

Also interesting to see that the bastards see the Roman throne as theirs, they view themselves as legitimate?

A - People in the past by and large believed in their faith and were loathe to give it up. Henry IV is the outlier, not the norm, for a reason.Question: with the Persians being the sole supporter of the Mesopotamian right now and the fact their population are mostly Muslims, wouldnt it be wiser for them to convert?

B - If they do convert to Islam whatever slim chance they have of retaking the Roman throne is out the window.

Well, it depends on whether Athena and Demetrios are still around. The dynasty can still survive but it's unlikely we will see it long-term or reach the theoretical heights it could've had because Herakleios is legitimately a piece of garbage.you know it would be funny if this war would be the cause of the current dynasty of rhomania to be overthrown

I thought they converted as part of the deal but even if not, I doubt it's a big deal since the locals never made a huge fuss about them being Christian. Generally, as long as their rights are well respected (kind of an important thing due to the Great Crime), treated well, and left alone, they won't rebel against Alexandros or his family.Question: with the Persians being the sole supporter of the Mesopotamian right now and the fact their population are mostly Muslims, wouldnt it be wiser for them to convert?

Honestly, their defiance against the Tourmarches will probably encourage some to rally behind him rather than throw their gates to the Romans.

B444 confirmed that the Sideroi dynasty continues into modern day Rhomania sooooyou know it would be funny if this war would be the cause of the current dynasty of rhomania to be overthrown

So maybe he changed his mind and the end of the present crisis is the Koinon of the Greeks sorry Romans under the Archon Prostates.B444 confirmed that the Sideroi dynasty continues into modern day Rhomania soooo

The Archon what? 😳So maybe he changed his mind and the end of the present crisis is the Koinon of the Greeks sorry Romans under the Archon Prostates.

The Lord Protector for you Hellenically challenged.The Archon what? 😳

Both the human organ and the verb have similar etymologies.The Archon what? 😳

Threadmarks

View all 52 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Rhomania's General Crisis, Part 17.2: Sustaining the War, Part 3 March Updates on Hiatus Rhomania's General Crisis, Part 17.3: Sustaining the War, Part 4 Rhomania's General Crisis, Part 17.4: Sustaining the War, Part 5 Rhomania's General Crisis, Part 18.0: Shall the Sword Devour Forever? Part 1 Rhomania's General Crisis, Part 18.1: Shall the Sword Devour Forever? Part 2 Rhomania's General Crisis, Part 18.2: Shall the Sword Devour Forever? Part 3 Rhomania's General Crisis, Part 19.0: Go Forward, Part 1

Share: