TrueI agree but knowing Reagan and Attawater they could try to taint RFK with association. Depends on how negative the campaign will be I suppose

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Blue Skies in Camelot (Continued): An Alternate 80s and Beyond

- Thread starter President_Lincoln

- Start date

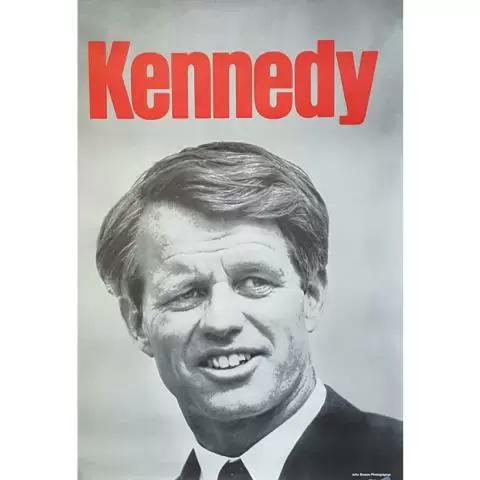

Great explanation of RFK's geopolitical views. It's sometimes hard to forget that initially during the early stages of the Cuban Missile Crisis Bobby was actually pushing for an invasion of Cuba and later supported the idea of the blockade. Given he served as Secretary of Defense ITTL and has seen the disasters of the Romney/Bush era I imagine Bobby being very frank and blunt about how he views the Pentagon and Defense spending in a potential administration under his.Excellent questions. Without giving too much away here, let's take a glimpse into RFK's potential foreign policy.

Bobby Kennedy has had a long, complex journey to become the person he is on the eve of the 1980 presidential election. As a young attorney, freshly graduated from the University of Virginia Law School, Bobby was a fervent anti-Communist. He even worked alongside Roy Cohn under the infamous Joseph McCarthy (a family friend of the Kennedys) for a time in the early 1950s. Later, during the early years of his brother's presidency, Bobby continued his preference for an aggressive foreign policy. The Cuban Missile Crisis, however, represented a major turning point in Kennedy's thinking. As the world stepped right up to the brink of global thermonuclear war and the end of civilization as we know it, RFK learned a valuable lesson: cooler heads prevail. You have to be tough, of course. Bobby Kennedy's entire world view is pure moralistic Catholicism. He believes in an ethical universe. There is good and there is evil. "White hats" and "black hats", he calls them, just like in an old Western film. But sometimes, the people you like are not the "white hats". The world is more nuanced, more complex. You have to be honest with yourself. You have to be fair. As he has matured, he's gained experience, and through that, wisdom. He understands that careful judgement must be exercised when it comes to geopolitics, especially in this thermonuclear age.

A dyed-in-the-wool liberal, Kennedy believes very deeply in individual freedom and autonomy, along with other human rights, like dignity and respect. His foreign policy, if elected, would be human rights-centric, for sure. It would also be tough and confrontational where it can be. The phrase "a fighter for peace" comes to mind. Some have called Bobby Kennedy "ruthless". So amend that to "a ruthless fighter for peace". Kennedy would neither back down from communist aggression, nor aggravate it with provocative geopolitical moves. Immediately, he would likely project strength to the hardliners who have just risen to power in Moscow (Suslov, Ustinov, and Gromyko) while still keeping open backchannel negotiations for renewed détente. Learning from the disastrous Bay of Pigs Invasion, and Romney and Bush's stumbles in Cambodia, Kennedy believes that "military adventurism" is a fool's errand. Kennedy would like to build on the work his brother did in limiting nuclear proliferation. A nuclear "freeze" and even arms-reduction treaties are certainly on the table, if the Soviets will play ball. As a Senator, Kennedy quietly supported President Bush's decision to travel to Beijing, shake hands with Chairman Zhou and recognize the People's Republic of China. Though he favors continued defense of Taiwan as a geopolitical reality, a "One China Policy" that does not recognize Beijing's control over the vast majority of China would be nonsensical.

On a personal level, Bobby has decades of experience as an informal diplomat. First as a well-off Irish-American socialite, then as Secretary of Defense in the latter half of JFK's administration. While Jack was seen as cool and intellectual, "the first Irish-American Brahmin", Bobby is tough, no-nonsense, and morally righteous. "The first Irish-American Puritan".

Hope this helps!

I never thought of Mitt Romney ending up as President ITTL just because given what happened to his father he perhaps would not get involved in politicsWe sure do!👍

If anything I just thought that would inspire him even moreso to enter politics. With the slain former president as his father Mitt would be like JFK Jr. wherein the press and the public would be awaiting the return of a Romney to the White House (like the restoring of Camelot IOTL).I never thought of Mitt Romney ending up as President ITTL just because given what happened to his father he perhaps would not get involved in politics

That is a good point and if the time line goes the way Kennedy forever predicted with Shirley temple black and Hillary president in the 1990s and JFK Jr as president for the 2000s 2008 could be seen as Mitt Romney's timeIf anything I just thought that would inspire him even moreso to enter politics. With the slain former president as his father Mitt would be like JFK Jr. wherein the press and the public would be awaiting the return of a Romney to the White House (like the restoring of Camelot IOTL).

Good pointIf anything I just thought that would inspire him even moreso to enter politics. With the slain former president as his father Mitt would be like JFK Jr. wherein the press and the public would be awaiting the return of a Romney to the White House (like the restoring of Camelot IOTL).

A likely possibility.If anything I just thought that would inspire him even moreso to enter politics. With the slain former president as his father Mitt would be like JFK Jr. wherein the press and the public would be awaiting the return of a Romney to the White House (like the restoring of Camelot IOTL).

Very interesting idea... Very interesting indeed. 😉If anything I just thought that would inspire him even moreso to enter politics. With the slain former president as his father Mitt would be like JFK Jr. wherein the press and the public would be awaiting the return of a Romney to the White House (like the restoring of Camelot IOTL).

Yesss... very interesting.Very interesting idea... Very interesting indeed. 😉

Chapter 130

Chapter 130: Zé Canjica - A (Brief) Trip Through Latin America in the Late 1970s

Above: A view of a busy street in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in the early 1970s (left); Armed militiamen, some of them children, during the Salvadoran Civil War (right)

Above: A view of a busy street in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in the early 1970s (left); Armed militiamen, some of them children, during the Salvadoran Civil War (right)

“It's raining

And the rain will wet someone

That once fell all wet in my arms

It's not true, No, it can't be

It's not true, No, it can't be

Silence, go away

Leave me, forgive me

Silence, go away

Leave me, forgive me” - “Zé Canjica” by Jorge Ben

“We must support, morally and financially, the struggle of our Latin American friends against political, economic, and social injustice.” - John F. Kennedy, on the Alliance for Progress

“I have never made a friend from whom I could not separate, and I have never made an enemy that I could not approach.” - Tancredo Neves, 25th President of Brazil

Latin America was, like much of the world in the 1970s, going through a period of immense economic, political, and social upheaval.

Though the decade began promisingly enough for the region, the Americans under President John F. Kennedy pursued an “Alliance for Progress” and sent significant economic and diplomatic aid to develop the region, much of that came to a grinding, screeching halt following the election of Republican George Romney to the White House in 1968. The onset of “stagflation” and the Romney oil shock of 1971 resulted in political support for foreign aid back in the States plummeting. When it came time to make up budget shortfalls, something that the efficiency-obsessed Romney considered a priority, foreign aid was one of the first things cut. This was not the only area in which the Republican administrations that followed JFK’s two terms would come to haunt the people of Latin America.

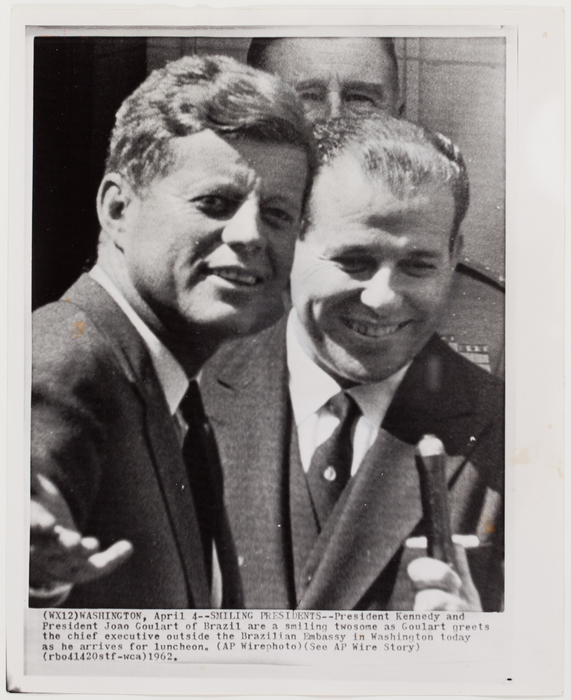

John F. Kennedy lived and breathed foreign policy. Charming, but assertive, he was a natural diplomat. Deeply intellectual, he was capable of holding complex, nuanced views of delicate situations, a skill that had only been honed by his leadership during the Cuban Missile Crisis. This unique perspective made him capable and willing to see unlikely allies and turn potential challenges into opportunities. A prime example of this was his outreach to João Goulart, President of Brazil in 1964, helping to prevent a military coup in that country. Despite Goulart’s left-wing beliefs, Kennedy understood that Goulart was a nationalist at heart. He supported the economic policies he did because he wanted his country to be free from “imperializers” in both Washington and Moscow. Ever wily and charismatic, JFK convinced Goulart that only through cooperation and friendship with America could Brazil continue to grow and reach its true potential. The two leaders managed to come to an understanding and even an uneasy friendship. Goulart would be reelected president in 1965, then conclude his second term in 1969, leaving office shortly after his American counterpart. More on Goulart’s successor in a moment.

Above: JFK meets with President João Goulart of Brazil (left); President Romney meets with Colonel Carlos Arana Osorio of Guatemala in 1971 (right).

George Romney, in a sense, could not have been more different from his predecessor. Formerly the Governor of Michigan before his election to the presidency, Romney had next to no foreign policy experience. Thus, he was seen as somewhat naive by many world leaders. Not helping matters much was his decision to defer on foreign affairs almost entirely to Secretary of State Richard Nixon and his allies, Secretary of Defense Omar Bradley, and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger, informally referred to as “the triumvirate”. Nixon, Bradley, and Kissinger favored a much more realpolitik approach, and that extended to Latin America. Gone were the Kennedy’s Administration’s insistence on human rights and dedication to democratic ideals. Instead, there would be renewed support for authoritarian regimes, including that of President Osorio of Guatemala, which was still in the midst of a bloody civil war. So long as someone opposed communism, they were a friend of the Romney and later, Bush Administrations.

For his part, George Bush was far more skilled at foreign policy than Romney had been. Nonetheless, he was much more adept at coalition building and tactics than he was at what he called “the vision thing”. Unlike Kennedy, who saw his role as potentially transformative, and Romney, who mostly just nodded and said his lines when it came to the world stage, Bush saw himself as a team captain, like he’d been on the baseball team back at Yale when he’d met Babe Ruth. America led the Free World. Bush led America. Therefore, it was his job to play a good defense against “the other team”.

Above: George Bush shakes hands with Chairman Zhou Enlai on his visit to Beijing, China in 1973.

Though he wagged his finger at Kissinger and Bradley for supporting a military coup in Chile without his knowledge, and even fired SecState Nixon for it, he did not fundamentally disagree with the logic behind the attempt. Even as Bush shook hands with Chairman Zhou Enlai and visited Beijing, even as he brokered peace in the Middle East in the Kennebunkport Accords, the underlying ideology of his foreign policy was, in no way fundamentally different from those of the Romney years. He opposed communism. That was “the other team”.

As a result, even as aid and support for Latin American development from Washington dwindled, meddling and imperialism made something of a return throughout the 1970s. In Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama, and perhaps most controversially, El Salvador, authoritarian regimes and right-wing dictatorships were propped up in the name of “fighting communism” abroad. The last of these, which resulted in the Salvadoran Civil War, would last for decades, and cause immense bloodshed and suffering in that country.

Finally, there was Mo Udall. The “smiling cowboy” from Arizona did his best to correct what he saw as his country’s “dangerous” and “shameful” behavior of late. He instituted a foreign policy that sought to return to the Kennedy Doctrine: support for human rights; democracy; and a willingness to “bear any burden” and “pay any price” to protect these freedoms. Unfortunately, domestic concerns utterly consumed what would turn out to be Udall’s one and only term in office. Despite his good intentions, Udall’s attention was simply elsewhere, mostly the energy crisis, inflation, and unemployment. His Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty, successfully negotiated with Yuri Andropov and the Soviets, failed to be ratified by the Senate. Perhaps the one major foreign policy achievement of his administration, the signing of a treaty with Panama to return control of the Panama Canal by 1999, was undercut by the fact that Panama was ruled by Omar Torrijos, a dictator.

Would relations between America and the rest of the Western Hemisphere improve as the new decade - the 1980s - dawned? Which path would America take: one of friendship and justice; or one of opportunism and self-interest?

Only time would tell.

…

In the meantime, Latin America continued to forge its own path into the latter quarter of the 20th century.

Though Brazil managed to avoid its close brush with a military coup thanks to American support in 1964, the country still had a long way to go in terms of its development. Thankfully, the more or less centrist Social Democrats pulled together a broad coalition of farmers, urban laborers, and other working class Brazilians in order to support their reform-minded agenda. This included land reform, construction of infrastructure along with hospitals, schools, and universities. Most importantly, it meant an end to graft and political corruption, so long one of the Republic’s weaknesses. Tancredo Neves, prime minister under President Goulart, was elected to succeed him in 1969. Less of a “leftist” than his predecessor, but still dedicated to Brazilian national autonomy, Neves instituted a “slow, but steady” approach to developing his country’s economy. While some in the country called for low wages to push for a rapid rise in exports and in-flow of foreign capital, Neves favored instead a “grassroots” policy of economic justice. After all, to quote President Kennedy, “a rising tide lifts all boats”. Neves saw that, in the long run, “miracles” of the West German and Japanese variety were unsustainable. You couldn’t grow your economy that fast indefinitely. Inevitably, you’d run into a wall. Whether it was racking up debt, or a spike in inflation (which was already high at the start of the 70s), there were long term costs to short term binging.

Instead, with only a brief interruption when Neves was temporarily booted out in the 1972 presidential election in favor of Auro de Moura Andrade, “the King of Cattle”, a conservative, who chased the allure of rapid growth and an export-based economy, the country diligently worked to create stable growth. This came with the development of agriculture, energy, mining, and increasingly, manufacturing as powerful industries. Brazil also became an urban nation, with more than 67% of its population crowding into booming cities, in particular, São Paulo. Meanwhile, Brazil won its third world cup victory in 1970, sending national pride into orbit. The national team’s star player, Pelé, became one of the world’s biggest celebrities, increasing Brazilian “soft power” internationally. The government became directly involved in the economy, as it invested heavily in new highways, bridges, and railroads. Steel mills, petrochemical factories, hydroelectric power plants, and nuclear reactors were built by the large state-owned companies Eletrobras and Petrobras. To reduce the dependency on imported oil, the ethanol industry was heavily promoted. Though Brazil did borrow an unhealthy amount from foreign lenders during Andrade’s term, following the 1973 oil shock, the financial “bleeding” ebbed when Neves returned to power. Though the 1978 oil shock, brought about by the Iranian Revolution, hurt the Brazilian economy, because its fundamentals were strong, the recession which followed proved short-lived.

By the early 1980s, Brazil, already the western hemisphere’s second largest country in both land area and population, was ready to break out onto the world stage in a big way. A strong American ally, sure, but also a regional and middle power in its own right, an emerging power, one that would demand its own place at the table of nations.

…

Above: Argentine officers take part in an Independence Day parade in Buenos Aires (left); the Argentinian Flag (right).

Above: Argentine officers take part in an Independence Day parade in Buenos Aires (left); the Argentinian Flag (right).

To Brazil’s south, the other nation that many felt “should” have become an emerging power in Latin America was Argentina. Unfortunately, that country was, as it had numerous times before in its history, struggling with intense economic and political instability.

Following the military’s ouster of President Isabel Peron in 1976, the country fell to yet another dictatorship under Jorge Rafael Videla. Videla, in turn, prosecuted the so-called “Dirty War” against his political enemies, real and perceived.

The "Dirty War" (Spanish: Guerra Sucia) was part of “Operation Condor”, which included the participation of other right-wing dictatorships in the Southern Cone. This operation, largely backed and funded by the American CIA, was state terrorism at the highest level. From 1969 to 1977, when funding for the operation was pulled by the Udall administration, the United States assisted the dictators of South America in political repression and even assassination of left-wing thinkers and activists.

In line with these objectives, the “Dirty War” involved state terrorism in Argentina and elsewhere in the Southern Cone against political dissidents, with military and security forces employing violence against left-wing guerrillas, as well as anyone believed to be associated with socialism or somehow contrary to the capitalistic economic policies of the regime. Victims of the violence in Argentina alone included an estimated 15,000 to 30,000 left-wing activists and militants, including trade unionists, students, journalists, Marxists, Peronist guerrillas, and alleged sympathizers. The opposing guerrillas' victims numbered nearly 500–540 military and police officials and up to 230 civilians. Argentina received technical support and military aid from the United States government during the Romney and Bush administrations.

The Videla regime instituted the “National Reorganization Process”, often shortened to “proceso”. The Proceso shut down the Argentine Congress, removed the judges on the Supreme Court, banned political parties and unions, and perpetrated numerous “forced disappearances” of opponents to the regime. By 1979, Videla’s grasp on power was near absolute, and he began to turn his gaze toward unifying the country behind him, to gain legitimacy. A military base was installed on the uninhabited British South Sandwich Islands in the South Atlantic Ocean, setting the stage for the eventual invasion of the Falklands, though that, is a story for another time.

…

Another nation that, like Brazil, seemed poised for success in the 1970s was Venezuela. Fueled by the exploding price of oil throughout the decade, Venezuela, which holds the world’s largest known oil reserves, became one of the world’s leading energy exporters. A country of some 14 million, Venezuela also benefited from a strong democratic tradition, free press, and largely peaceful relations with its neighbors. However, there were chinks in the country's armor.

Serving as president from 1974 to 1979, Carlos Andrés Pérez proved less generous with hand-outs than previous presidents, such as Rómulo Betancourt had been. Despite initially rejecting liberalization policies, his economic agenda was later focused on cutting subsidies, privatizations, and legislation to attract foreign investment. Naím began at the lowest rung of economic liberalization, which was freeing controls on prices and a ten percent increase in that of gasoline. Low gas prices were previously held to be sacrosanct in Venezuela. The increase in petrol price fed into a 30 percent increase in fares for public transport, which resulted in widespread public anger.

Unlike Neves in Brazil, Pérez was not a visionary who could see the potentially disastrous long-term impacts of too-rapid development funded by taking on foreign debt. Turning Venezuela into what outside observers called “South America’s Saudi Arabia”, Pérez spent lavishly on development of exporting industries, while imposing austerity for the common people.

Come the 1980s, this resulted in a series of economic and political crises that Venezuela was utterly unprepared for. And unlike other countries in Latin America, Pérez could not readily turn to the Estados Unidos for assistance, as the Romney, Bush, and later Udall administrations did not see his country as being particularly in need of their assistance. They figured that with oil prices as high as they were, Venezuela should be doing well. They assumed, as did many foreign observers, that Pérez and his administration were simply corrupt and wetting their beaks with all that oil revenue.

Indeed, even by 1979, there were dark storm clouds on the horizon for Venezuela.

Next Time on Blue Skies in Camelot: The Republicans Line Up for 1980

Nice good simple summary of Latin America in this timeline it will be interesting to see how the alternate 80s affect them moreChapter 130: Zé Canjica - A (Brief) Trip Through Latin America in the Late 1970s

Above: A view of a busy street in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in the early 1970s (left); Armed militiamen, some of them children, during the Salvadoran Civil War (right)

“It's raining

And the rain will wet someone

That once fell all wet in my arms

It's not true, No, it can't be

It's not true, No, it can't be

Silence, go away

Leave me, forgive me

Silence, go away

Leave me, forgive me” - “Zé Canjica” by Jorge Ben

“We must support, morally and financially, the struggle of our Latin American friends against political, economic, and social injustice.” - John F. Kennedy, on the Alliance for Progress

“I have never made a friend from whom I could not separate, and I have never made an enemy that I could not approach.” - Tancredo Neves, 25th President of Brazil

Latin America was, like much of the world in the 1970s, going through a period of immense economic, political, and social upheaval.

Though the decade began promisingly enough for the region, the Americans under President John F. Kennedy pursued an “Alliance for Progress” and sent significant economic and diplomatic aid to develop the region, much of that came to a grinding, screeching halt following the election of Republican George Romney to the White House in 1968. The onset of “stagflation” and the Romney oil shock of 1971 resulted in political support for foreign aid back in the States plummeting. When it came time to make up budget shortfalls, something that the efficiency-obsessed Romney considered a priority, foreign aid was one of the first things cut. This was not the only area in which the Republican administrations that followed JFK’s two terms would come to haunt the people of Latin America.

John F. Kennedy lived and breathed foreign policy. Charming, but assertive, he was a natural diplomat. Deeply intellectual, he was capable of holding complex, nuanced views of delicate situations, a skill that had only been honed by his leadership during the Cuban Missile Crisis. This unique perspective made him capable and willing to see unlikely allies and turn potential challenges into opportunities. A prime example of this was his outreach to João Goulart, President of Brazil in 1964, helping to prevent a military coup in that country. Despite Goulart’s left-wing beliefs, Kennedy understood that Goulart was a nationalist at heart. He supported the economic policies he did because he wanted his country to be free from “imperializers” in both Washington and Moscow. Ever wily and charismatic, JFK convinced Goulart that only through cooperation and friendship with America could Brazil continue to grow and reach its true potential. The two leaders managed to come to an understanding and even an uneasy friendship. Goulart would be reelected president in 1965, then conclude his second term in 1969, leaving office shortly after his American counterpart. More on Goulart’s successor in a moment.

Above: JFK meets with President João Goulart of Brazil (left); President Romney meets with Colonel Carlos Arana Osorio of Guatemala in 1971 (right).

George Romney, in a sense, could not have been more different from his predecessor. Formerly the Governor of Michigan before his election to the presidency, Romney had next to no foreign policy experience. Thus, he was seen as somewhat naive by many world leaders. Not helping matters much was his decision to defer on foreign affairs almost entirely to Secretary of State Richard Nixon and his allies, Secretary of Defense Omar Bradley, and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger, informally referred to as “the triumvirate”. Nixon, Bradley, and Kissinger favored a much more realpolitik approach, and that extended to Latin America. Gone were the Kennedy’s Administration’s insistence on human rights and dedication to democratic ideals. Instead, there would be renewed support for authoritarian regimes, including that of President Osorio of Guatemala, which was still in the midst of a bloody civil war. So long as someone opposed communism, they were a friend of the Romney and later, Bush Administrations.

For his part, George Bush was far more skilled at foreign policy than Romney had been. Nonetheless, he was much more adept at coalition building and tactics than he was at what he called “the vision thing”. Unlike Kennedy, who saw his role as potentially transformative, and Romney, who mostly just nodded and said his lines when it came to the world stage, Bush saw himself as a team captain, like he’d been on the baseball team back at Yale when he’d met Babe Ruth. America led the Free World. Bush led America. Therefore, it was his job to play a good defense against “the other team”.

Above: George Bush shakes hands with Chairman Zhou Enlai on his visit to Beijing, China in 1973.

Though he wagged his finger at Kissinger and Bradley for supporting a military coup in Chile without his knowledge, and even fired SecState Nixon for it, he did not fundamentally disagree with the logic behind the attempt. Even as Bush shook hands with Chairman Zhou Enlai and visited Beijing, even as he brokered peace in the Middle East in the Kennebunkport Accords, the underlying ideology of his foreign policy was, in no way fundamentally different from those of the Romney years. He opposed communism. That was “the other team”.

As a result, even as aid and support for Latin American development from Washington dwindled, meddling and imperialism made something of a return throughout the 1970s. In Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama, and perhaps most controversially, El Salvador, authoritarian regimes and right-wing dictatorships were propped up in the name of “fighting communism” abroad. The last of these, which resulted in the Salvadoran Civil War, would last for decades, and cause immense bloodshed and suffering in that country.

Finally, there was Mo Udall. The “smiling cowboy” from Arizona did his best to correct what he saw as his country’s “dangerous” and “shameful” behavior of late. He instituted a foreign policy that sought to return to the Kennedy Doctrine: support for human rights; democracy; and a willingness to “bear any burden” and “pay any price” to protect these freedoms. Unfortunately, domestic concerns utterly consumed what would turn out to be Udall’s one and only term in office. Despite his good intentions, Udall’s attention was simply elsewhere, mostly the energy crisis, inflation, and unemployment. His Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty, successfully negotiated with Yuri Andropov and the Soviets, failed to be ratified by the Senate. Perhaps the one major foreign policy achievement of his administration, the signing of a treaty with Panama to return control of the Panama Canal by 1999, was undercut by the fact that Panama was ruled by Omar Torrijos, a dictator.

Would relations between America and the rest of the Western Hemisphere improve as the new decade - the 1980s - dawned? Which path would America take: one of friendship and justice; or one of opportunism and self-interest?

Only time would tell.

…

In the meantime, Latin America continued to forge its own path into the latter quarter of the 20th century.

Above: Tancredo Neves, 25th and 27th President of Brazil. He served from 1969 - 1973, and again from 1977 - 1985. He passed away shortly before the conclusion of what would have been his second consecutive, third overall presidential term.

Though Brazil managed to avoid its close brush with a military coup thanks to American support in 1964, the country still had a long way to go in terms of its development. Thankfully, the more or less centrist Social Democrats pulled together a broad coalition of farmers, urban laborers, and other working class Brazilians in order to support their reform-minded agenda. This included land reform, construction of infrastructure along with hospitals, schools, and universities. Most importantly, it meant an end to graft and political corruption, so long one of the Republic’s weaknesses. Tancredo Neves, prime minister under President Goulart, was elected to succeed him in 1969. Less of a “leftist” than his predecessor, but still dedicated to Brazilian national autonomy, Neves instituted a “slow, but steady” approach to developing his country’s economy. While some in the country called for low wages to push for a rapid rise in exports and in-flow of foreign capital, Neves favored instead a “grassroots” policy of economic justice. After all, to quote President Kennedy, “a rising tide lifts all boats”. Neves saw that, in the long run, “miracles” of the West German and Japanese variety were unsustainable. You couldn’t grow your economy that fast indefinitely. Inevitably, you’d run into a wall. Whether it was racking up debt, or a spike in inflation (which was already high at the start of the 70s), there were long term costs to short term binging.

Above: Auro de Moura Andrade, who served a single term as Brazil’s 26th president from 1973 - 1977 (left); Pelé, arguably the greatest football player of all time (right).

Instead, with only a brief interruption when Neves was temporarily booted out in the 1972 presidential election in favor of Auro de Moura Andrade, “the King of Cattle”, a conservative, who chased the allure of rapid growth and an export-based economy, the country diligently worked to create stable growth. This came with the development of agriculture, energy, mining, and increasingly, manufacturing as powerful industries. Brazil also became an urban nation, with more than 67% of its population crowding into booming cities, in particular, São Paulo. Meanwhile, Brazil won its third world cup victory in 1970, sending national pride into orbit. The national team’s star player, Pelé, became one of the world’s biggest celebrities, increasing Brazilian “soft power” internationally. The government became directly involved in the economy, as it invested heavily in new highways, bridges, and railroads. Steel mills, petrochemical factories, hydroelectric power plants, and nuclear reactors were built by the large state-owned companies Eletrobras and Petrobras. To reduce the dependency on imported oil, the ethanol industry was heavily promoted. Though Brazil did borrow an unhealthy amount from foreign lenders during Andrade’s term, following the 1973 oil shock, the financial “bleeding” ebbed when Neves returned to power. Though the 1978 oil shock, brought about by the Iranian Revolution, hurt the Brazilian economy, because its fundamentals were strong, the recession which followed proved short-lived.

By the early 1980s, Brazil, already the western hemisphere’s second largest country in both land area and population, was ready to break out onto the world stage in a big way. A strong American ally, sure, but also a regional and middle power in its own right, an emerging power, one that would demand its own place at the table of nations.

…

Above: Argentine officers take part in an Independence Day parade in Buenos Aires (left); the Argentinian Flag (right).

To Brazil’s south, the other nation that many felt “should” have become an emerging power in Latin America was Argentina. Unfortunately, that country was, as it had numerous times before in its history, struggling with intense economic and political instability.

Following the military’s ouster of President Isabel Peron in 1976, the country fell to yet another dictatorship under Jorge Rafael Videla. Videla, in turn, prosecuted the so-called “Dirty War” against his political enemies, real and perceived.

The "Dirty War" (Spanish: Guerra Sucia) was part of “Operation Condor”, which included the participation of other right-wing dictatorships in the Southern Cone. This operation, largely backed and funded by the American CIA, was state terrorism at the highest level. From 1969 to 1977, when funding for the operation was pulled by the Udall administration, the United States assisted the dictators of South America in political repression and even assassination of left-wing thinkers and activists.

In line with these objectives, the “Dirty War” involved state terrorism in Argentina and elsewhere in the Southern Cone against political dissidents, with military and security forces employing violence against left-wing guerrillas, as well as anyone believed to be associated with socialism or somehow contrary to the capitalistic economic policies of the regime. Victims of the violence in Argentina alone included an estimated 15,000 to 30,000 left-wing activists and militants, including trade unionists, students, journalists, Marxists, Peronist guerrillas, and alleged sympathizers. The opposing guerrillas' victims numbered nearly 500–540 military and police officials and up to 230 civilians. Argentina received technical support and military aid from the United States government during the Romney and Bush administrations.

The Videla regime instituted the “National Reorganization Process”, often shortened to “proceso”. The Proceso shut down the Argentine Congress, removed the judges on the Supreme Court, banned political parties and unions, and perpetrated numerous “forced disappearances” of opponents to the regime. By 1979, Videla’s grasp on power was near absolute, and he began to turn his gaze toward unifying the country behind him, to gain legitimacy. A military base was installed on the uninhabited British South Sandwich Islands in the South Atlantic Ocean, setting the stage for the eventual invasion of the Falklands, though that, is a story for another time.

…

Another nation that, like Brazil, seemed poised for success in the 1970s was Venezuela. Fueled by the exploding price of oil throughout the decade, Venezuela, which holds the world’s largest known oil reserves, became one of the world’s leading energy exporters. A country of some 14 million, Venezuela also benefited from a strong democratic tradition, free press, and largely peaceful relations with its neighbors. However, there were chinks in the country's armor.

Serving as president from 1974 to 1979, Carlos Andrés Pérez proved less generous with hand-outs than previous presidents, such as Rómulo Betancourt had been. Despite initially rejecting liberalization policies, his economic agenda was later focused on cutting subsidies, privatizations, and legislation to attract foreign investment. Naím began at the lowest rung of economic liberalization, which was freeing controls on prices and a ten percent increase in that of gasoline. Low gas prices were previously held to be sacrosanct in Venezuela. The increase in petrol price fed into a 30 percent increase in fares for public transport, which resulted in widespread public anger.

Unlike Neves in Brazil, Pérez was not a visionary who could see the potentially disastrous long-term impacts of too-rapid development funded by taking on foreign debt. Turning Venezuela into what outside observers called “South America’s Saudi Arabia”, Pérez spent lavishly on development of exporting industries, while imposing austerity for the common people.

Come the 1980s, this resulted in a series of economic and political crises that Venezuela was utterly unprepared for. And unlike other countries in Latin America, Pérez could not readily turn to the Estados Unidos for assistance, as the Romney, Bush, and later Udall administrations did not see his country as being particularly in need of their assistance. They figured that with oil prices as high as they were, Venezuela should be doing well. They assumed, as did many foreign observers, that Pérez and his administration were simply corrupt and wetting their beaks with all that oil revenue.

Indeed, even by 1979, there were dark storm clouds on the horizon for Venezuela.

Next Time on Blue Skies in Camelot: The Republicans Line Up for 1980

Thank you!Nice good simple summary of Latin America in this timeline it will be interesting to see how the alternate 80s affect them more

Rising Steel Warrior

Banned

Hello President_Lincoln I'm a newly registered user hailing from my home countries of Canada and the USA respectively with some interest in your timeline because of it's POD. I know you allow guest updates when I read this and maybe someday I could write one on your behalf. Anyway, I'm following your timeline.Thank you!I have more to say about Mexico, as I recently mentioned in the thread. But I wanted to have some more time to flesh that out.

Last edited:

Excellent. Few right-wing governments in Latin America here, thankfully, though sad to see we still have some form of Argentina's military government.

Welcome!Hello President_Lincoln I'm a newly registered user hailing from my home countries of Canada and the USA with some interest in your timeline because of it's POD. I know you allow guest updates when I read this and maybe someday I could write one on your behalf. Anyway, I'm following your timeline.

Good question! Yes. ITTL, Leo Ryan survived his ordeal in Jonestown, thanks to backup from the Secret Service and some quick thinking by Ryan, his friend Congressman Dan Quayle (R - IN), who accompanied him, and their respective staffs. Both Ryan and Quayle were injured, but are still alive, well, and serving in Congress.Also, I just remembered something. What's Leo Ryan up to? I don't think Jonestown happened, is he still in Congress?

Thank you!Excellent. Few right-wing governments in Latin America here, thankfully, though sad to see we still have some form of Argentina's military government.

Rising Steel Warrior

Banned

Haven't conceived one yet but I would like to tell you about gap80's Kentucky Fried Politics. What do you think of it if you have read the entire thing?Welcome!I'm so happy that you found your way here. Thank you for your readership and for your interest. Do you have ideas about what you might like to write a guest update about?

Good question! Yes. ITTL, Leo Ryan survived his ordeal in Jonestown, thanks to backup from the Secret Service and some quick thinking by Ryan, his friend Congressman Dan Quayle (R - IN), who accompanied him, and their respective staffs. Both Ryan and Quayle were injured, but are still alive, well, and serving in Congress.

Absolutely love that timeline!Haven't conceived one yet but I would like to tell you about gap80's Kentucky Fried Politics. What do you think of it if you have read the entire thing?

Rising Steel Warrior

Banned

Me too! It's been a little inactive since it ended with the recent post from September 14 but the Photos Thread is still active though. There are even some similarities between both as well as notable differences.Absolutely love that timeline!

Share: