Agreed with Charles and Diana they were not a good match. With the Pianist I hope another director makes the movie in this timeline because that story needs to be told.Charles and Diana were two people who should have never married each other, IMO...

Like the earlier version of the #MeToo movement as well--Polanski deserved what he got. In OTL and TTL, he had a horrible childhood (his mother was gassed in the Auschwitz death camp (and was four months pregnant), and his father was in a concentration camp) and had to live with a number of Catholic families as a child in Poland (the movie The Pianist was likely inspired by this)--and, in OTL, he lost his wife, Sharon Tate, who was eight and a half months pregnant, to the Manson family murders.

That aside, however, there is no excuse for taking advantage of (and outright raping) young girls, and Polanski is where he belongs in TTL (I'm surprised an inmate didn't try to take out Polanski himself--child rapists do not fare well in prison)...

Good chapters, BTW, and like the end of the Troubles in the latest chapter...

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Blue Skies in Camelot (Continued): An Alternate 80s and Beyond

- Thread starter President_Lincoln

- Start date

Wonder what will happen to Diana ITTL. Someone suggested she could end up marrying JFK Jr and I really like that idea. It would certainly make her a real People's Princess 😅Agreed with Charles and Diana they were not a good match. With the Pianist I hope another director makes the movie in this timeline because that story needs to be told.

Yeah that's true though when would they cross paths that's the questionWonder what will happen to Diana ITTL. Someone suggested she could end up marrying JFK Jr and I really like that idea. It would certainly make her a real People's Princess 😅

Maybe JFK Jr spends some time living in London and similar to OTL Harry and Megan mutual friends send them on a blind date together and that's how they meet?🤔Yeah that's true though when would they cross paths that's the question

I would also apologize as well to you genius. It's just whenever we hear or think about Nixon, we're all triggered or always think negative about him. His reputation was already good if it wasn't for The Watergate Scandal that ended his presidency. And as for you genius, you really brought the best of me whenever we're talking about history and I thank you for that as well.Apologies guys I kinda started the whole "Nixon 84" thing. I apologise if it's gotten out of hand. After re-reading the first part of Blue Skies I believed that there were enough hints that Nixon might be President. I figured 84 would be the best chance after Udall's term ends. I still believe either Nixon or Rumsfeld will probably run in 84. Again who knows 🤷♂️

Ultimately it's the author's story and we are just along for the ride

Cheers mate no worries 😀👍 Thanks for thatI would also apologize as well to you genius. It's just whenever we hear or think about Nixon, we're all triggered or always think negative about him. His reputation was already good if it wasn't for The Watergate Scandal that ended his presidency. And as for you genius, you really brought the best of me whenever we're talking about history and I thank you for that as well.

That could workMaybe JFK Jr spends some time living in London and similar to OTL Harry and Megan mutual friends send them on a blind date together and that's how they meet?🤔

I'm thinking that maybe at the same time the New Historians are writing their books (or the first intifada gets rolling) documents about the full extent of Israeli war crimes (i.e. the Dawayima Massacre being one of the most prominent) or things like GL-18/17028 get leaked. It would debunk a lot of Israeli talking points and show that the Arabs didn't just up and leave; This could possibly increase sympathy for the Arab world right at a time when they use non violence.

That was already my suggestion and I apologize for my intuition because I can already feel something great between JFK, Jr. and Diana. With them being alive ITTL, I can already expect the best of them.Wonder what will happen to Diana ITTL. Someone suggested she could end up marrying JFK Jr and I really like that idea. It would certainly make her a real People's Princess 😅

The genius will find a way on how this story would work.Maybe JFK Jr spends some time living in London and similar to OTL Harry and Megan mutual friends send them on a blind date together and that's how they meet?🤔

Chapter 126

Chapter 126 - Everybody Has a Dream - President Udall Makes A Difficult Decision

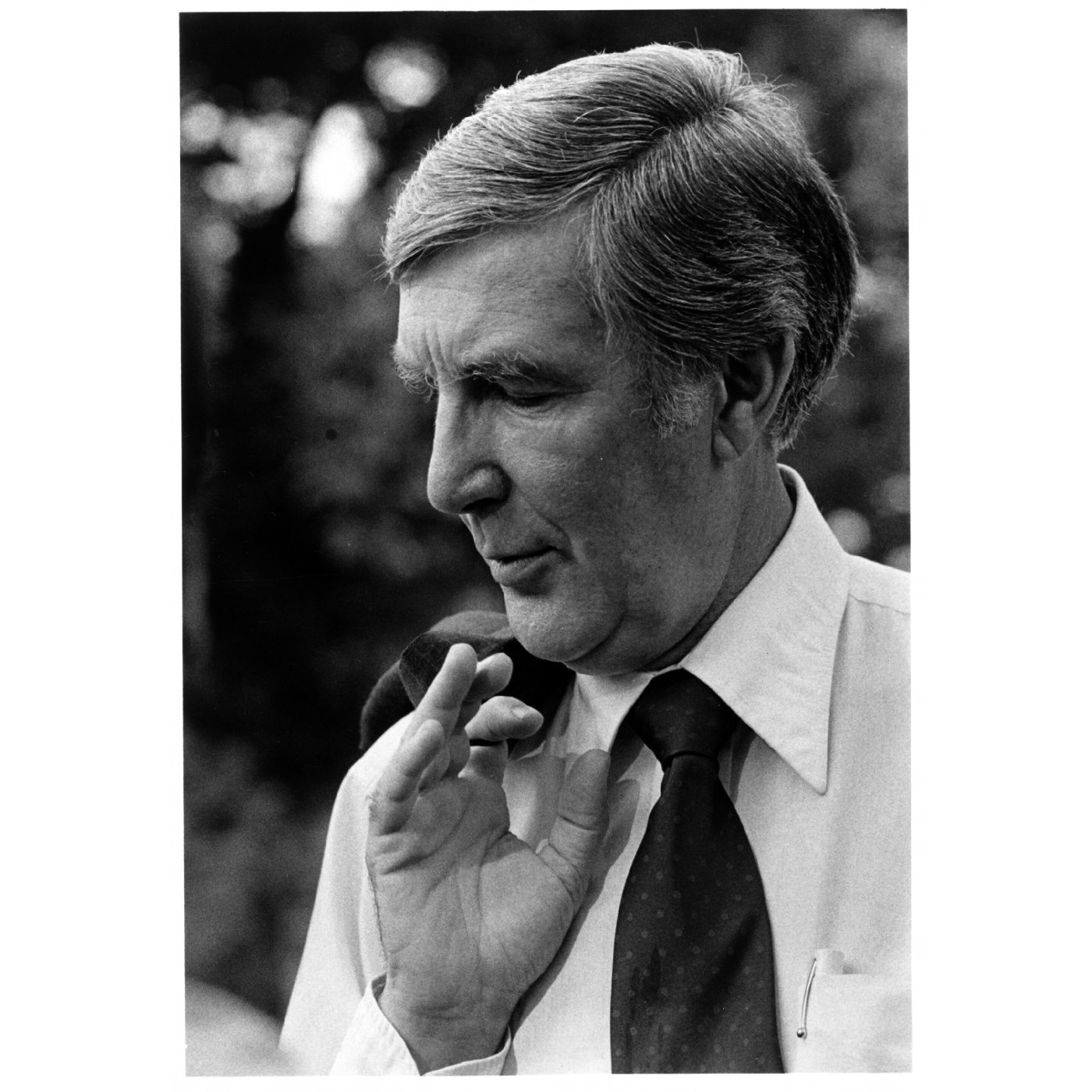

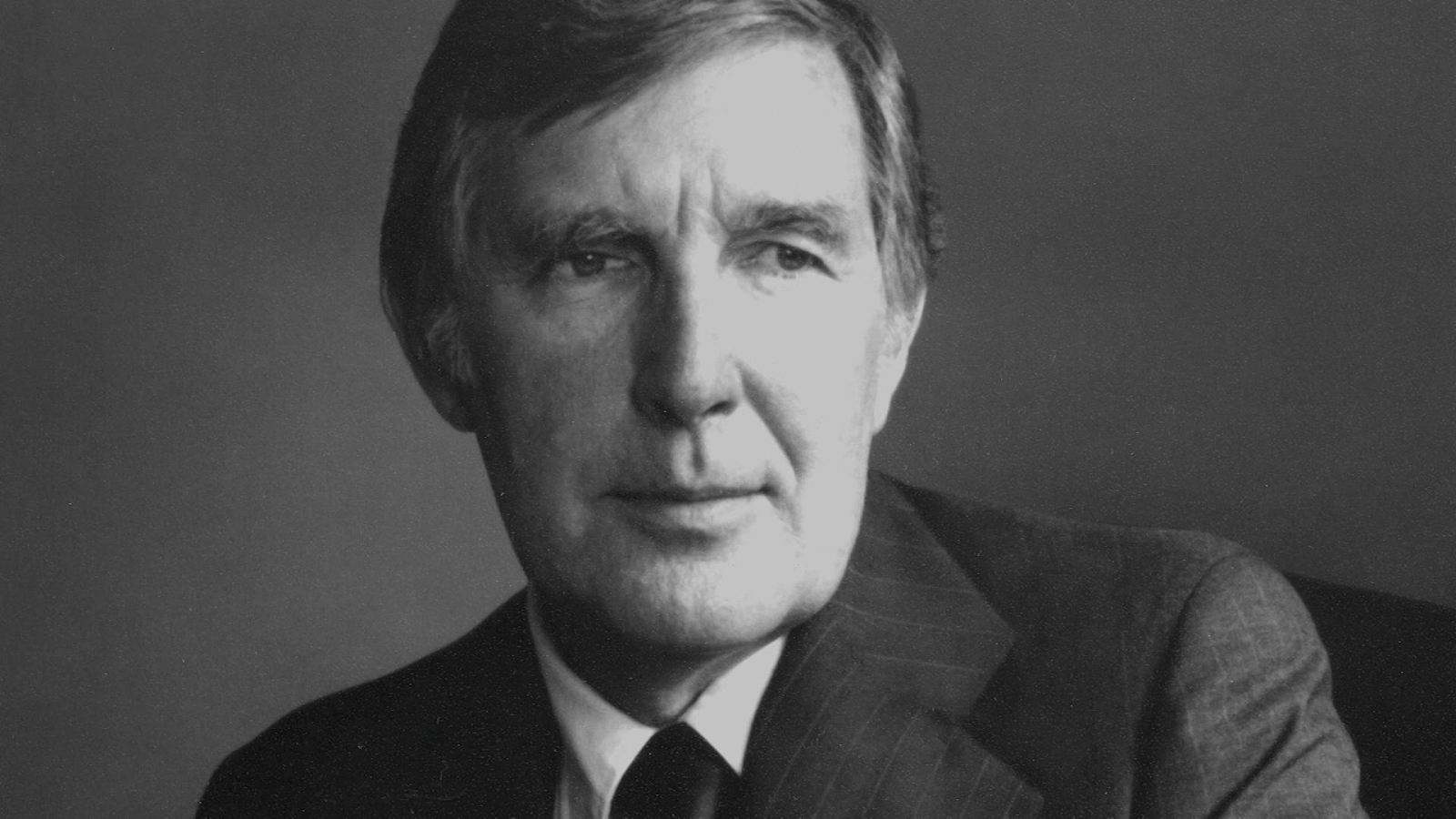

Above: President Mo Udall (D - AZ) gives his first major press interview since revealing the true status of his personal health to the nation (left); First Lady Ella Udall comments on her husband’s decision not to seek a second term (right).“While in these days of quiet desperation

As I wander through the world in which I live

I search everywhere, for some new inspiration

But it's more than cold reality can give

If I need a cause for celebration

Or a comfort I can use to ease my mind

I rely on my imagination

And I dream of an imaginary time

I know that everybody has a dream

Everybody has a dream

And this is my dream, my own

Just to be at home

And to be all alone...with you” - “Everybody Has a Dream” by Billy Joel

“Big Job; Big Man” - Udall 1976 presidential campaign slogan

“Nothing will spoil a big man’s life like too much truth.” - Mo Udall, quoting Will Rogers

It all started with a few sleepless nights in May, 1979. Despite his best efforts, the president could not seem to catch a wink.

It became a frustrating routine. He and First Lady Ella Udall would finish up their day shortly before ten. They’d turn into their bedroom in the White House residence. Within about fifteen minutes, Ella would slip off to sleep. The president, however, would not. He’d spend most of the night tossing and turning. Ultimately, he might finally slip away for an hour or two, only to be jarred awake by his alarm at dawn. Ella asked Mo to set aside another hour or two before his day began, but the president felt that he couldn’t. There were security briefings to attend. Policy meetings. Planning sessions. Soon, campaigning would be added to that already full-to-bursting schedule. Ella Udall did not look forward to that.

The first lady, a former staffer for the postal subcommittee in the House of Representatives (that was where she’d met Mo), did not especially love politics. She was, at best, a reluctant campaigner. She accepted her husband’s workaholic lifestyle, but insisted that he try to get more sleep.

After weeks of trying every tip and trick in the book: exercising and showering before bed; no caffeine within six hours of bedtime; keeping the residence dark and quiet; breathing exercises; the president made another, slightly startling discovery.

He was in the Oval Office one afternoon, signing a number of official dispatches, when his Chief of Staff, Ted Sorensen, took one of them, stared at it, then began checking it against a number of others. After a minute of this, Udall looked up from the Resolute Desk and broke into a weary grin.

“I didn’t spell my name wrong, did I?”

“No, Mr. President. But your handwriting…” Sorensen trailed off, then cleared his throat. “Is it just me, or does it seem… smaller than usual? Are you doing that on purpose?”

Udall certainly was not. He set down his pen, pushed his chair back from his desk, and adjusted his glasses. His good eye narrowed. Staring at the bottom line, where he’d signed, he realized that his markings did, in fact, seem smaller than usual. At first, he thought his mind, or his vision, might be playing tricks on him. One of the quirks of having only one functioning eye was that he sometimes struggled with depth perception. But comparing that morning’s signatures against a stack of others that he’d signed just a year prior showed the truth of the matter, clear as day. The letters had shrunk. They’d also changed shape. Only slightly. Almost imperceptibly. But they clearly had.

Later that evening, the President felt more fatigued than usual. The first lady grew concerned. Her husband was usually such an upbeat, energetic man. For him to be so worn down, something must be seriously wrong. She pleaded with Mo to summon the Physician to the president, Rear Admiral William M. Lukash, of the US Navy. Though Mo insisted everything was fine, he eventually caved and sent for the doctor. That decision, and the resulting tests which followed it, would change both the First Couple’s lives and the history of the United States, and indeed, the world, forever.

Above: Dr. Raymond Damadian, inventor of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (“MRI”).

Dr. Lukash began his inquiry with something of a routine check up. He listened to the president report his symptoms: difficulty sleeping; smaller than usual handwriting; even an occasional loss of smell. Lukash checked for more routine explanations, but found that Udall did not appear to be suffering from any kind of infection. Initially, he recommended increased time for rest, a slightly eased schedule, and prescribed benzodiazepine, a hypnotic, to help the president sleep. He assured both Mo and the first lady that if the president’s bearing did not improve in a few days’ time, he would reassess the situation.

It did not. The pills didn’t work. Udall continued to drag.

Lukash next investigated a possible cardiovascular condition, or possibly a complication from Udall’s near-brush with assassination on the campaign trail back in 76. The president underwent a top secret psychiatric evaluation, to see if he might be suffering from TAPS, which can result from traumatic events and discourage restful sleep, among other symptoms. Both sets of tests came back negative. Mo’s heart was fine. And though he still occasionally had flashes of that terrible day in San Francisco, he seemed to mostly be coping well. Even his arm, where he’d been hit, had made a full recovery.

Unsure of what else to try, Lukash turned to a team of his trusted fellow physicians, who recommended that his patient be flown to Bethesda Naval Hospital in Maryland, so that he could undergo an at the time experimental procedure: having his brain scanned via Magnetic Resonance Imagery (MRI). Though the technology was still in its infancy, the first successful images of the brain taken only the year before, it nonetheless held enormous potential for helping to diagnose issues with the brain and nervous system, which had, historically, been infamously difficult. Though Ella fretted about her husband being slid inside the “bizarre contraption” waiting for them in Bethesda, the president agreed that if it might help, he would do it.

Udall flew over to Bethesda on Marine One on Saturday, May 12th, 1979. At the time, the press hardly took note of it. It wasn’t exactly unheard of for the president to fly there for routine tests. Few could understand how much of a firestorm would follow.

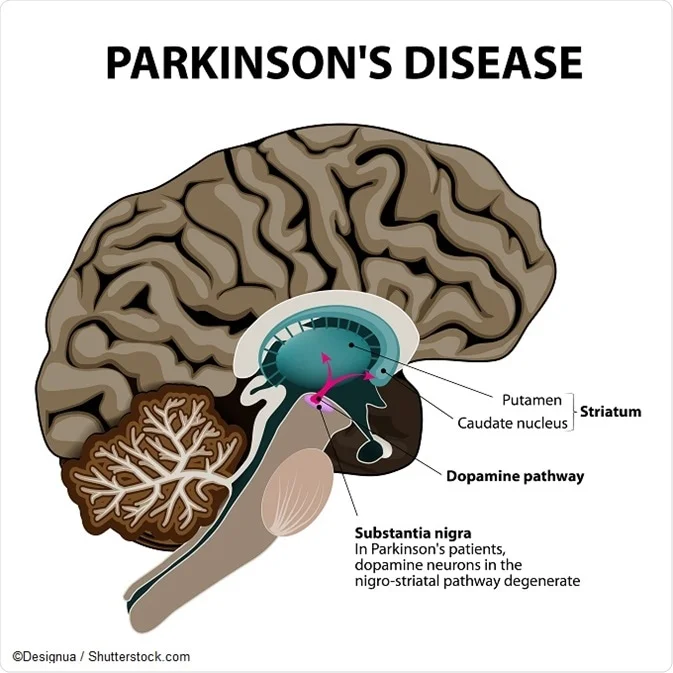

The results of the MRI came out a few hours after the test was complete. Dr. Lukash, Dr. Damadian, and a number of the country’s top neuroscientists convened, under the utmost secrecy, to study them. President Udall’s brain became one of the first few hundred to be imaged in this way. It would also share another, more unfortunate honor: it was the first documented case of MRI imaging being used to help diagnose a case of Parkinson’s Disease.

First diagnosed in the early 19th century, Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is a chronic degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that affects both the motor and non-motor systems of the body. The symptoms usually emerge slowly, but as the disease worsens, non-motor symptoms become increasingly common. Early signs like difficulty sleeping, rigidity of movement, and slight tremor eventually give way to more serious issues with cognition, behavior, and sensory systems. The brain and its network of messengers slowly break down, increasingly incapable of doing their jobs. Lukash and his team of doctors were able to diagnose the president due to the visible neuron damage on the MRI images. Lukash had suspected PD before the trip to Bethesda, but had hoped that he was mistaken. The new technology silenced any doubts. Reluctantly, he took the news back to the president and first lady, still waiting in their suite at the hospital. They were devastated by the news, especially Mo.

Though still in its early stages, there was no way to know how quickly the disease would advance. At nearly 57 years old, Udall was not an “early onset” case. Most sufferers from PD will be diagnosed around the age of 60. Statistically, average life expectancy following diagnosis can range anywhere from 7 to 15 years. It really depends upon the individual case. Ella turned to her husband. Already, she could see the pain gathering like a storm cloud upon his face. The real pain. Not only was he being handed an eventual death sentence, but she knew the next question he was going to ask.

“The next five years…” He clenched the sheets of the hospital bed into a fist. “Will I keep my mind?”

Ella held back a sob. She’d been right, only her husband hadn’t said it the way she’d expected. In her mind, she heard: “Can I still run for reelection?”

Lukash frowned. He said he did not know. PD was full of uncertainty then, and in many ways, still is. He took the president and first lady through the likely progression: increasing physical troubles, followed by a slow cognitive decline. Eventually, he told them, the President’s mood would change. His ability to focus, to control his thinking, to make split second decisions, would break down. Remaining as apolitical as he could, while still being sensitive to the personalities involved, Lukash gave his personal advice:

“You should have no problems finishing your term, Mr. President.”

Term. Singular. Only one. Udall held back his fury.

He had spent most of his adult life seeking public office. For more than a decade, he’d toiled away in the House of Representatives, champion of the little guy, of all the causes that no one else wanted. He’d fought and clawed his way to the nomination three years prior, against a crowded field. Since taking office, he’d finally seen Medicare expand to include all Americans, taken on the oil trusts and their big money, and made significant contributions to infrastructure, energy, and environmental policy. He’d stood up for the rights of First Americans, and advocated for making voting easier across the nation. He hadn’t gotten to tax reform, or foreign affairs as much as he would have liked. That was Second Term stuff. Building a legacy. He realized, sitting there in his hospital bed with growing horror, that he would never get to do them. That would be somebody else’s turn. Somebody else’s legacy to build.

Udall would later remark that this was the lowest moment of his life.

In the days that followed, the President slowly disseminated the news of his diagnosis on a need to know basis. He began with Stew, his brother, and still his closest political advisor, if only in an unofficial capacity. He then called his children, including his son, Mark. Due to his workaholic nature, the President had never been overly close with his kids. He and Mark talked for over an hour, the President finally breaking down into tears in the Oval Office. He apologized for not being there more for Mark, for his siblings.

“There’s still time, Dad.” Mark said.

That stuck with Mo. He told Mark he loved him and they hung up for the night.

Half-heartedly, the president met with his official advisors, Chief of Staff Sorensen, Senate Majority Leader Russell B. Long (D - LA) and House Speaker Tip O’Neill (D - MA). He told them the truth, and, though he knew what they would say, sought their advice on the most important decision he would ever make: could he still run for a second term? Further, if he could, should he?

Stunned to silence by the news, the gathered men and women largely stared at their feet until, at length, Senator Long cleared his throat.

“Mr. President,” Long’s jowls often quivered as he spoke. Not this time. “I know loss. My daddy was gunned down for trying to help the people of our state. I was sixteen when that happened. I can’t speak for your children, or the first lady, but speaking for myself… I think we all owe it to you to tell you square: you need to do what's right for you and your family.”

Udall nodded. Others began to chime in. Or pile on. Mo thought, a little bemused.

Even if the president’s health remained strong throughout his second term, a huge gamble in itself, there was the question of political liability. Washington was a town where everybody talked. After the J. Edgar Hoover Affair, the days of covering up dirty laundry in politics were not exactly over, but it was a much more difficult proposition. Sooner or later, word would leak to the press. The nation would know that there was, in essence, a ticking time bomb in the head of their commander in chief. Even if Udall did all the right things, went public first, got out ahead of it, he would eventually be pinned with having to give answers to tough questions that the American people would not want to hear. He would have to tell them that there was no way of knowing for certain when his mind would start to decline. Republicans would pillory him for that, even if they did so respectfully. Reagan would keep his hands clean, but would his attack dogs? Would they really let this opportunity pass them by, to unseat a popular incumbent? The attack ads wrote themselves.

“We want a President who can still think!”

Udall thought of Ella. He’d never been a very good husband to her, he realized. She loved his wit and his kindness, not his career choice. She wanted nothing more than to retire with him, so that they could live a happy, private life together. He realized that she’d been growing increasingly depressed since moving into the White House. For her sake, for his kids, and for the good of the nation, there was really only one decision he could make.

Morris K. Udall, 38th President of the United States, would not seek a second term.

…

True to their word, no one in the president’s inner circle or advisors leaked the news to the press. They handled the issue with sensitivity and decorum. The White House Communications team arranged for Udall to deliver a primetime address on the issue to the entire nation from the Oval Office. This would happen on Friday, June 28th, 1979. The address would be carried on all three networks, and would preempt regularly scheduled programming. Folks tuning in to catch Tales of the Unexpected or The Dukes of Hazzard would instead see the president, seated at the Resolute Desk. Just after 8pm eastern, he began to speak.

“Ladies and gentlemen, my fellow Americans,

I speak to you tonight with a message from the heart, a message that is both bittersweet and important. It's a message that I want to deliver with the same candor you've come to expect from me these past few years. In this, I will do my best.

Earlier this month, I was diagnosed by my personal physician, Rear Admiral William Lukash, with Parkinson's disease. Now, I know that this disease might be unfamiliar to you, so let me break it down for you in plain language. Parkinson's is a condition that affects the way the brain controls our movements. Sometimes, it causes tremors, stiffness, and a bit of trouble with balance. Presently, I have not experienced any symptoms more advanced than this. My doctors tell me that - presently - they consider me to be in tip top shape, all things considered.

Folks, I want you to know that this diagnosis will not keep me from fulfilling my duties as your President. I've got a fantastic medical team, and they assure me that I can still serve out the remainder of my term effectively. I may have to slow down a bit on the basketball court, but my commitment to this great nation and to all of you remains as strong as ever.

Unfortunately, however, this news does force me to ask myself a lot of big questions. I’m sure you know where this is heading.

After a lot of thought, reflection, and conversations with my family, I have decided not to seek re-election to the Presidency in 1980. It wasn't an easy decision, believe me. I've had the privilege of serving this wonderful country. I love this job. But sometimes, we have to make choices that prioritize what's most important to us.

My family has always been near and dear to my heart. They've supported me through thick and thin, and it's high time that I return that love and support in kind. I want to spend more time with them, to cherish every moment, and make memories together that they can cherish after I’m gone, whenever that may be.

So, my fellow Americans, I'm going to be here, working for you, for the remainder of my term. We've got important work to do together, and I'm committed to seeing it through. I'll do it with the same optimism and dedication that I've always brought to this office.

Thank you for your trust, your support, and your smiles. It's been an incredible honor to serve as your President, and I'll cherish the memories we've made together. Let's keep forming that ‘more perfect union’, hand in hand, as we always have.

God bless you all, and God bless the United States of America.”

…

The president’s announcement rattled the nation to its core.

It wasn’t unheard of for the President of the United States to suffer from health issues. Franklin D. Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy struggled with polio and Addison’s Disease respectively, and still managed to successfully lead their country through difficult times. In the past, however, details, including the true extent of the commander in chief’s maladies, were always carefully concealed from the public. Udall’s candor about his diagnosis was virtually unheard of in politics, American or otherwise. In the years following the end of his term, Udall would be praised by historians and pundits alike for his decision, and for handling it in the way that he did.

At the time, however, his address prompted a great deal of uncertainty.

For one thing, Udall was broadly popular in the summer of 1979. His approval rating held steady at about 52%. Though conservatives loathed his policies and moderates were increasingly put off by his more progressive attitude, the average, apolitical American liked their folksy, western “cowboy in chief”. They liked his broad smile, his tall frame, and his legendary wit. At a time when relations with the Soviets and the People’s Republic of China were still uncertain, at a time when the economy was only just barely beginning to show the first, sputtering signs of recovery, their leader was being forced to step away after 1980.

Hundreds of thousands of letters poured into the White House from across the nation. Well-wishers. People of all political affiliations felt sympathy for the president and his family. Americans affected by Parkinson’s called Mo’s speech “heroic”, and pressed him to become an advocate for public awareness and for increased research into the disease, how to diagnose it, and most importantly, how to treat it. The role of MRI in Udall’s diagnosis also became a hot topic, especially in the medical and scientific communities. If anyone had been doubtful about MRI’s potential utility before, those doubts were swiftly banished.

Of course, there were darker reactions as well. On the far right, paleoconservative provocateurs, former John Birchers, and other conspiracy-minded folks celebrated the downfall of their perceived “enemy”, the pinko “fake cowboy” from Arizona. Jerry Falwell, the “political preacher” from Virginia, provoked outrage and controversy when he declared that “the president’s infirmity is a scourge from God, a sign of his divine wrath at the policies of a non-believer.”

Obviously, this story went far beyond just Mo and his family. It became part of the stage-setting for perhaps the most consequential election in a generation.

…

Though no one would say it openly, at least, not immediately, the president’s diagnosis and subsequent decision not to seek re-election also held massive political ramifications.

The Democrats, who felt confident of their ability to rally around Mo for four more years, were suddenly thrown into disarray. Who would they nominate to carry the banner for them in 1980? Could they still count on “incumbent’s advantage” when they no longer had an incumbent?

To some, Vice President Lloyd Bentsen seemed the obvious answer. If the incumbent president cannot run again, then isn’t his number two the next best thing? Bentsen did have a number of things going for him, from the outset. As the incumbent VP, he was intimately tied to the administration in the eyes of the public. Even if many of Udall’s accomplishments had been “too liberal” for moderate Bentsen, he could keep quiet on his prior opposition to them and simply ride the wave of their popularity. Though he waited a few months before forming an exploratory committee, out of respect for his boss, the vice president did indeed intend to run. He’d meant to do so in 1984, after all. What was four years earlier?

But Bentsen immediately had more than his share of detractors as well.

For one thing, Bentsen, though well-spoken and skilled at debate, was not particularly charismatic. With Former Vice President Ronald Reagan’s nomination by the Republicans all but certain to many, a potential Reagan-Bentsen match-up seemed dubious, at best. Bentsen had beaten Reagan on the debate stage four years prior. “You’re no Harry Truman” was still a household line in politics. But one debate did not and would not win an entire campaign. Simply put, Bentsen did not excite people the way that Udall did, or the way that many Democrats feared Reagan would.

This presented a conundrum: if not Bentsen, then who?

Alternatives presented themselves largely depending on which wing of the Democratic Party one consulted. Communitarians throughout the south immediately pitched Senator Jimmy Carter of Georgia. Carter, then a former governor, had only narrowly decided against a bid in 1976. With his own folksy charm, 1980 really felt like it could be his year. There was New York Governor Hugh Carey, the former Congressman from Brooklyn, widely hailed across the country as “the man who saved New York” for his efforts at resolving NYC’s budgetary crisis. Carey held a certain panache for the more Old School, New Deal liberals in the party, though it wasn’t clear he even wanted the job. A widower, Carey seemed content to continue to govern his home state in Albany. Then there was Jerry Brown, “Governor Moonbeam” of California, who had taken over from James Roosevelt after his retirement in 1974. Brown was eccentric, and youthful, only 42 in 1980, but his caustic personality and unpredictable nature made him an unlikely pick.

Other names: Arkansas Senator Dale Bumpers (“every northerner’s favorite southerner”); Florida Governor Reubin Askew; floated around for a while. Several of these would ultimately make a bid for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1980. They were joined by one more name. The big one. The heavy hitter. The one who everyone in America waited to hear from, the moment that the clamor from President Udall’s announcement died down.

Senator Robert F. Kennedy, of New York.

Fifty-four years old in 1979, Bobby had been a Senator from New York for the past nine years. Of course, before that, he had famously worked in his brother’s White House for all eight years of his administration, first as Attorney General, then later as Secretary of Defense. Jack Kennedy’s chief advisor, closest confidant, and his little brother, Bobby Kennedy was, despite his relative youth, arguably the “elder statesman” for his generation of Democratic politicians.

Passionate, ruthless, and absolutely tough-as-nails, “the first Irish Puritan” had been forced to stand aside in 1976 due to the lingering fallout from the Hoover Affair. Kennedy’s reputation had taken a hit, especially within the Black community, for his prior authorization of wiretaps on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Stokley Carmichael, and other civil rights leaders. In the years since, Senator Kennedy had apologized for this decision, calling it, “the greatest mistake” of his career. He’d also worked tirelessly to restore his connections with African-Americans, Hispanic-Americans, and other minority communities, championing their causes in the Senate, in the streets, and on television screens and radio airwaves.

On a personal level, Kennedy had all but given up his presidential aspirations after 1976. Mo Udall championed many of the same causes he did. Thus, RFK was happy to support him from the sidelines, as Mo had once supported Jack. But Udall’s decision to step down sparked a fire in Bobby’s stomach. He recalled the conversation he’d had with Jack in the Oval Office, all those years before.

“One day, it’ll be you here, Bobby. It’ll be your call.”

Shortly after Udall’s announcement of his diagnosis, Senator Kennedy called the president to wish him the best, and to express his sympathy. About a month later, he spoke to his beloved wife, Ethel, about the prospect of him running in 1980. She gave him her blessing, as did an ailing Jack.

“It’s your time now.” The former President Kennedy said, simply, from his wheelchair. “Give ‘em Hell.”

Bobby hugged his brother and promised that he would.

Next Time on Blue Skies in Camelot: More Foreign Affairs!

...

Author's Note: So... I know that I have some explaining to do....

I know that up to this point, pretty much all of the foreshadowing pointed toward President Udall running for a second term. I even started this "Act" of the story with a quote, supposedly from Udall's second nomination acceptance speech at the 1980 convention. I want to take a moment to apologize if you feel that you've been hoodwinked. This was not always my plan. But after much careful consideration, and writing two versions of this chapter, I eventually deleted the other and decided to go with this one.

IOTL, Mo was diagnosed with Parkinson's in 1979 as well. Part of his rationale for not running for president again in 1984 was because his disease had progressed, even by that time. He continued to serve in Congress until 1991, by which time his condition had deteriorated and he no longer felt he was able to serve. Given this information, I initially planned to have Mo announce his condition to the public, and forge on, hoping to explain how his diagnosis did not prevent him from being an effective commander in chief. However, the more I thought about getting to this point in the Timeline, the more I began to have second thoughts.

For one thing, serving as President of the United States is orders of magnitude more demanding than serving as a member of the House of Representatives. Even if Udall's campaign schedule could be lightened at all, he would still be subjected to the a gauntlet of seemingly endless policy meetings, tense negotiations over policy both domestic and foreign, and security briefings. Should there be some kind of military crisis, he would need to be physically fit and sound of mind for hours, potentially days on end, running on very little sleep. As mentioned in the chapter, there are also the political considerations.

Would it be possible for Udall to explain his condition to the public? To make them see that, for the time being, he is still more than capable of serving as their president? Possibly. He is charismatic. The people generally like him. But then again, even if he could, it would expend a great deal of his political capital just getting them to believe in him. To have faith that the disease won't progress too rapidly. I know that both IOTL and ITTL, Udall was a very career-focused person. He often prioritized his time in office over time with his wives and kids. IOTL, Ella Udall tragically died by suicide in the late 1980s, a decision that was possibly made in part because she did chafe against the limelight of political campaigns. ITTL, with the white hot media spotlight on them, I could see Udall deciding that the right thing, the honorable thing to do, would be to stand aside and find another path for his public advocacy.

I will cover all of this in more detail moving forward. As per OTL, Mo Udall will live into the 1990s. I plan on having him become a very public advocate not just for Parkinson's awareness, but for all neurodegenerative disorders, raising money and campaigning for a cure.

I hope you all will still enjoy this TL despite this change in direction. I repeat that this decision was made after long, careful consideration.

As always, thanks for reading.

- President_Lincoln

RFK FOR PRESIDENT '80! LET'S FLIPPING GOOO!!!The one who everyone in America waited to hear from, the moment that the clamor from President Udall’s announcement died down.

Senator Robert F. Kennedy, of New York.

Good God. Still, the candor Mo Udall displayed is quite admirable and will certainly boost the credibility of the office. Not only that, but it seems we're once again having a Kennedy as the main character of this TL! I can't wait to see the primary challenges and the general election. Perhaps Reagan vs Kennedy? Or even Nixon vs Kennedy, like the '60 election.

I have to admit, that was also a significant element of my decision, from a narrative perspective.Good God. Still, the candor Mo Udall displayed is quite admirable and will certainly boost the credibility of the office. Not only that, but it seems we're once again having a Kennedy as the main character of this TL! I can't wait to see the primary challenges and the general election. Perhaps Reagan vs Kennedy? Or even Nixon vs Kennedy, like the '60 election.

I also agree that Udall's decision was a brave one. I think one of the real legacies of TTL's presidents (I hope) will be a more transparent federal government. Perhaps this can prevent the general public from forming as much of a distrust in the government, as happened IOTL after Watergate. Only time will tell, of course.

What?????😭 This was so unexpected and heartbreaking! I already knew beforehand that Udall in OTL suffered from Parkinson but the entire chapter just hit me like a gut punch. From the title to him being diagnosed to his conversation with the doctor and his speech to the American people, kudos to your writing as it feels so real. I want Mo to keep fighting but at the same time I understand his priorities regarding his family.

This was certainly a shock as we all thought, myself included, Udall would win re-election against Reagan handily in 1980. Now it's up in the air for the Democrats. While I'd like to see Bentsen run I can't deny the allure of Bobby Kennedy in 1980.

This was definitely subverting our expectations and it was so well done 👏👏👏

This was certainly a shock as we all thought, myself included, Udall would win re-election against Reagan handily in 1980. Now it's up in the air for the Democrats. While I'd like to see Bentsen run I can't deny the allure of Bobby Kennedy in 1980.

This was definitely subverting our expectations and it was so well done 👏👏👏

Also @President_Lincoln your on fire. Putting out these chapters like their a Disney plus MCU show 🤣😉👍

What?????😭 This was so unexpected and heartbreaking! I already knew beforehand that Udall in OTL suffered from Parkinson but the entire chapter just hit me like a gut punch. From the title to him being diagnosed to his conversation with the doctor and his speech to the American people, kudos to your writing as it feels so real. I want Mo to keep fighting but at the same time I understand his priorities regarding his family.

This was certainly a shock as we all thought, myself included, Udall would win re-election against Reagan handily in 1980. Now it's up in the air for the Democrats. While I'd like to see Bentsen run I can't deny the allure of Bobby Kennedy in 1980.

This was definitely subverting our expectations and it was so well done 👏👏👏

Thank you very much!Also @President_Lincoln your on fire. Putting out these chapters like their a Disney plus MCU show 🤣😉👍

My pace will have to slow a bit for the next week or two, unfortunately. I'll be travelling this weekend to visit family and have work and grad school to keep up with, as ever. But I should be able to keep more active than I have been for the first two-thirds of this year, certainly.

No problem. Good way to refresh yourself and get new ideas. 😀Thank you very much!I'm glad to hear that you're enjoying the updates.

My pace will have to slow a bit for the next week or two, unfortunately. I'll be travelling this weekend to visit family and have work and grad school to keep up with, as ever. But I should be able to keep more active than I have been for the first two-thirds of this year, certainly.

Well that took a turn. I'm disappointed but I understand, even though he will serve one term I think it goes without question that Udall was one of the better presidents in this timeline. With Udall out I'm just gonna say all the way with RFK.Chapter 126 - Everybody Has a Dream - President Udall Makes A Difficult DecisionAbove: President Mo Udall (D - AZ) gives his first major press interview since revealing the true status of his personal health to the nation (left); First Lady Ella Udall comments on her husband’s decision not to seek a second term (right).

“While in these days of quiet desperation

As I wander through the world in which I live

I search everywhere, for some new inspiration

But it's more than cold reality can give

If I need a cause for celebration

Or a comfort I can use to ease my mind

I rely on my imagination

And I dream of an imaginary time

I know that everybody has a dream

Everybody has a dream

And this is my dream, my own

Just to be at home

And to be all alone...with you” - “Everybody Has a Dream” by Billy Joel

“Big Job; Big Man” - Udall 1976 presidential campaign slogan

“Nothing will spoil a big man’s life like too much truth.” - Mo Udall, quoting Will Rogers

It all started with a few sleepless nights in May, 1979. Despite his best efforts, the president could not seem to catch a wink.

It became a frustrating routine. He and First Lady Ella Udall would finish up their day shortly before ten. They’d turn into their bedroom in the White House residence. Within about fifteen minutes, Ella would slip off to sleep. The president, however, would not. He’d spend most of the night tossing and turning. Ultimately, he might finally slip away for an hour or two, only to be jarred awake by his alarm at dawn. Ella asked Mo to set aside another hour or two before his day began, but the president felt that he couldn’t. There were security briefings to attend. Policy meetings. Planning sessions. Soon, campaigning would be added to that already full-to-bursting schedule. Ella Udall did not look forward to that.

The first lady, a former staffer for the postal subcommittee in the House of Representatives (that was where she’d met Mo), did not especially love politics. She was, at best, a reluctant campaigner. She accepted her husband’s workaholic lifestyle, but insisted that he try to get more sleep.

After weeks of trying every tip and trick in the book: exercising and showering before bed; no caffeine within six hours of bedtime; keeping the residence dark and quiet; breathing exercises; the president made another, slightly startling discovery.

He was in the Oval Office one afternoon, signing a number of official dispatches, when his Chief of Staff, Ted Sorensen, took one of them, stared at it, then began checking it against a number of others. After a minute of this, Udall looked up from the Resolute Desk and broke into a weary grin.

“I didn’t spell my name wrong, did I?”

“No, Mr. President. But your handwriting…” Sorensen trailed off, then cleared his throat. “Is it just me, or does it seem… smaller than usual? Are you doing that on purpose?”

Udall certainly was not. He set down his pen, pushed his chair back from his desk, and adjusted his glasses. His good eye narrowed. Staring at the bottom line, where he’d signed, he realized that his markings did, in fact, seem smaller than usual. At first, he thought his mind, or his vision, might be playing tricks on him. One of the quirks of having only one functioning eye was that he sometimes struggled with depth perception. But comparing that morning’s signatures against a stack of others that he’d signed just a year prior showed the truth of the matter, clear as day. The letters had shrunk. They’d also changed shape. Only slightly. Almost imperceptibly. But they clearly had.

Later that evening, the President felt more fatigued than usual. The first lady grew concerned. Her husband was usually such an upbeat, energetic man. For him to be so worn down, something must be seriously wrong. She pleaded with Mo to summon the Physician to the president, Rear Admiral William M. Lukash, of the US Navy. Though Mo insisted everything was fine, he eventually caved and sent for the doctor. That decision, and the resulting tests which followed it, would change both the First Couple’s lives and the history of the United States, and indeed, the world, forever.

Above: Dr. Raymond Damadian, inventor of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (“MRI”).

Dr. Lukash began his inquiry with something of a routine check up. He listened to the president report his symptoms: difficulty sleeping; smaller than usual handwriting; even an occasional loss of smell. Lukash checked for more routine explanations, but found that Udall did not appear to be suffering from any kind of infection. Initially, he recommended increased time for rest, a slightly eased schedule, and prescribed benzodiazepine, a hypnotic, to help the president sleep. He assured both Mo and the first lady that if the president’s bearing did not improve in a few days’ time, he would reassess the situation.

It did not. The pills didn’t work. Udall continued to drag.

Lukash next investigated a possible cardiovascular condition, or possibly a complication from Udall’s near-brush with assassination on the campaign trail back in 76. The president underwent a top secret psychiatric evaluation, to see if he might be suffering from TAPS, which can result from traumatic events and discourage restful sleep, among other symptoms. Both sets of tests came back negative. Mo’s heart was fine. And though he still occasionally had flashes of that terrible day in San Francisco, he seemed to mostly be coping well. Even his arm, where he’d been hit, had made a full recovery.

Unsure of what else to try, Lukash turned to a team of his trusted fellow physicians, who recommended that his patient be flown to Bethesda Naval Hospital in Maryland, so that he could undergo an at the time experimental procedure: having his brain scanned via Magnetic Resonance Imagery (MRI). Though the technology was still in its infancy, the first successful images of the brain taken only the year before, it nonetheless held enormous potential for helping to diagnose issues with the brain and nervous system, which had, historically, been infamously difficult. Though Ella fretted about her husband being slid inside the “bizarre contraption” waiting for them in Bethesda, the president agreed that if it might help, he would do it.

Udall flew over to Bethesda on Marine One on Saturday, May 12th, 1979. At the time, the press hardly took note of it. It wasn’t exactly unheard of for the president to fly there for routine tests. Few could understand how much of a firestorm would follow.

The results of the MRI came out a few hours after the test was complete. Dr. Lukash, Dr. Damadian, and a number of the country’s top neuroscientists convened, under the utmost secrecy, to study them. President Udall’s brain became one of the first few hundred to be imaged in this way. It would also share another, more unfortunate honor: it was the first documented case of MRI imaging being used to help diagnose a case of Parkinson’s Disease.

First diagnosed in the early 19th century, Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is a chronic degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that affects both the motor and non-motor systems of the body. The symptoms usually emerge slowly, but as the disease worsens, non-motor symptoms become increasingly common. Early signs like difficulty sleeping, rigidity of movement, and slight tremor eventually give way to more serious issues with cognition, behavior, and sensory systems. The brain and its network of messengers slowly break down, increasingly incapable of doing their jobs. Lukash and his team of doctors were able to diagnose the president due to the visible neuron damage on the MRI images. Lukash had suspected PD before the trip to Bethesda, but had hoped that he was mistaken. The new technology silenced any doubts. Reluctantly, he took the news back to the president and first lady, still waiting in their suite at the hospital. They were devastated by the news, especially Mo.

Though still in its early stages, there was no way to know how quickly the disease would advance. At nearly 57 years old, Udall was not an “early onset” case. Most sufferers from PD will be diagnosed around the age of 60. Statistically, average life expectancy following diagnosis can range anywhere from 7 to 15 years. It really depends upon the individual case. Ella turned to her husband. Already, she could see the pain gathering like a storm cloud upon his face. The real pain. Not only was he being handed an eventual death sentence, but she knew the next question he was going to ask.

“The next five years…” He clenched the sheets of the hospital bed into a fist. “Will I keep my mind?”

Ella held back a sob. She’d been right, only her husband hadn’t said it the way she’d expected. In her mind, she heard: “Can I still run for reelection?”

Lukash frowned. He said he did not know. PD was full of uncertainty then, and in many ways, still is. He took the president and first lady through the likely progression: increasing physical troubles, followed by a slow cognitive decline. Eventually, he told them, the President’s mood would change. His ability to focus, to control his thinking, to make split second decisions, would break down. Remaining as apolitical as he could, while still being sensitive to the personalities involved, Lukash gave his personal advice:

“You should have no problems finishing your term, Mr. President.”

Term. Singular. Only one. Udall held back his fury.

He had spent most of his adult life seeking public office. For more than a decade, he’d toiled away in the House of Representatives, champion of the little guy, of all the causes that no one else wanted. He’d fought and clawed his way to the nomination three years prior, against a crowded field. Since taking office, he’d finally seen Medicare expand to include all Americans, taken on the oil trusts and their big money, and made significant contributions to infrastructure, energy, and environmental policy. He’d stood up for the rights of First Americans, and advocated for making voting easier across the nation. He hadn’t gotten to tax reform, or foreign affairs as much as he would have liked. That was Second Term stuff. Building a legacy. He realized, sitting there in his hospital bed with growing horror, that he would never get to do them. That would be somebody else’s turn. Somebody else’s legacy to build.

Udall would later remark that this was the lowest moment of his life.

In the days that followed, the President slowly disseminated the news of his diagnosis on a need to know basis. He began with Stew, his brother, and still his closest political advisor, if only in an unofficial capacity. He then called his children, including his son, Mark. Due to his workaholic nature, the President had never been overly close with his kids. He and Mark talked for over an hour, the President finally breaking down into tears in the Oval Office. He apologized for not being there more for Mark, for his siblings.

“There’s still time, Dad.” Mark said.

That stuck with Mo. He told Mark he loved him and they hung up for the night.

Half-heartedly, the president met with his official advisors, Chief of Staff Sorensen, Senate Majority Leader Russell B. Long (D - LA) and House Speaker Tip O’Neill (D - MA). He told them the truth, and, though he knew what they would say, sought their advice on the most important decision he would ever make: could he still run for a second term? Further, if he could, should he?

Stunned to silence by the news, the gathered men and women largely stared at their feet until, at length, Senator Long cleared his throat.

“Mr. President,” Long’s jowls often quivered as he spoke. Not this time. “I know loss. My daddy was gunned down for trying to help the people of our state. I was sixteen when that happened. I can’t speak for your children, or the first lady, but speaking for myself… I think we all owe it to you to tell you square: you need to do what's right for you and your family.”

Udall nodded. Others began to chime in. Or pile on. Mo thought, a little bemused.

Even if the president’s health remained strong throughout his second term, a huge gamble in itself, there was the question of political liability. Washington was a town where everybody talked. After the J. Edgar Hoover Affair, the days of covering up dirty laundry in politics were not exactly over, but it was a much more difficult proposition. Sooner or later, word would leak to the press. The nation would know that there was, in essence, a ticking time bomb in the head of their commander in chief. Even if Udall did all the right things, went public first, got out ahead of it, he would eventually be pinned with having to give answers to tough questions that the American people would not want to hear. He would have to tell them that there was no way of knowing for certain when his mind would start to decline. Republicans would pillory him for that, even if they did so respectfully. Reagan would keep his hands clean, but would his attack dogs? Would they really let this opportunity pass them by, to unseat a popular incumbent? The attack ads wrote themselves.

“We want a President who can still think!”

Udall thought of Ella. He’d never been a very good husband to her, he realized. She loved his wit and his kindness, not his career choice. She wanted nothing more than to retire with him, so that they could live a happy, private life together. He realized that she’d been growing increasingly depressed since moving into the White House. For her sake, for his kids, and for the good of the nation, there was really only one decision he could make.

Morris K. Udall, 38th President of the United States, would not seek a second term.

…

True to their word, no one in the president’s inner circle or advisors leaked the news to the press. They handled the issue with sensitivity and decorum. The White House Communications team arranged for Udall to deliver a primetime address on the issue to the entire nation from the Oval Office. This would happen on Friday, June 28th, 1979. The address would be carried on all three networks, and would preempt regularly scheduled programming. Folks tuning in to catch Tales of the Unexpected or The Dukes of Hazzard would instead see the president, seated at the Resolute Desk. Just after 8pm eastern, he began to speak.

“Ladies and gentlemen, my fellow Americans,

I speak to you tonight with a message from the heart, a message that is both bittersweet and important. It's a message that I want to deliver with the same candor you've come to expect from me these past few years. In this, I will do my best.

Earlier this month, I was diagnosed by my personal physician, Rear Admiral William Lukash, with Parkinson's disease. Now, I know that this disease might be unfamiliar to you, so let me break it down for you in plain language. Parkinson's is a condition that affects the way the brain controls our movements. Sometimes, it causes tremors, stiffness, and a bit of trouble with balance. Presently, I have not experienced any symptoms more advanced than this. My doctors tell me that - presently - they consider me to be in tip top shape, all things considered.

Folks, I want you to know that this diagnosis will not keep me from fulfilling my duties as your President. I've got a fantastic medical team, and they assure me that I can still serve out the remainder of my term effectively. I may have to slow down a bit on the basketball court, but my commitment to this great nation and to all of you remains as strong as ever.

Unfortunately, however, this news does force me to ask myself a lot of big questions. I’m sure you know where this is heading.

After a lot of thought, reflection, and conversations with my family, I have decided not to seek re-election to the Presidency in 1980. It wasn't an easy decision, believe me. I've had the privilege of serving this wonderful country. I love this job. But sometimes, we have to make choices that prioritize what's most important to us.

My family has always been near and dear to my heart. They've supported me through thick and thin, and it's high time that I return that love and support in kind. I want to spend more time with them, to cherish every moment, and make memories together that they can cherish after I’m gone, whenever that may be.

So, my fellow Americans, I'm going to be here, working for you, for the remainder of my term. We've got important work to do together, and I'm committed to seeing it through. I'll do it with the same optimism and dedication that I've always brought to this office.

Thank you for your trust, your support, and your smiles. It's been an incredible honor to serve as your President, and I'll cherish the memories we've made together. Let's keep forming that ‘more perfect union’, hand in hand, as we always have.

God bless you all, and God bless the United States of America.”

…

The president’s announcement rattled the nation to its core.

It wasn’t unheard of for the President of the United States to suffer from health issues. Franklin D. Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy struggled with polio and Addison’s Disease respectively, and still managed to successfully lead their country through difficult times. In the past, however, details, including the true extent of the commander in chief’s maladies, were always carefully concealed from the public. Udall’s candor about his diagnosis was virtually unheard of in politics, American or otherwise. In the years following the end of his term, Udall would be praised by historians and pundits alike for his decision, and for handling it in the way that he did.

At the time, however, his address prompted a great deal of uncertainty.

For one thing, Udall was broadly popular in the summer of 1979. His approval rating held steady at about 52%. Though conservatives loathed his policies and moderates were increasingly put off by his more progressive attitude, the average, apolitical American liked their folksy, western “cowboy in chief”. They liked his broad smile, his tall frame, and his legendary wit. At a time when relations with the Soviets and the People’s Republic of China were still uncertain, at a time when the economy was only just barely beginning to show the first, sputtering signs of recovery, their leader was being forced to step away after 1980.

Hundreds of thousands of letters poured into the White House from across the nation. Well-wishers. People of all political affiliations felt sympathy for the president and his family. Americans affected by Parkinson’s called Mo’s speech “heroic”, and pressed him to become an advocate for public awareness and for increased research into the disease, how to diagnose it, and most importantly, how to treat it. The role of MRI in Udall’s diagnosis also became a hot topic, especially in the medical and scientific communities. If anyone had been doubtful about MRI’s potential utility before, those doubts were swiftly banished.

Of course, there were darker reactions as well. On the far right, paleoconservative provocateurs, former John Birchers, and other conspiracy-minded folks celebrated the downfall of their perceived “enemy”, the pinko “fake cowboy” from Arizona. Jerry Falwell, the “political preacher” from Virginia, provoked outrage and controversy when he declared that “the president’s infirmity is a scourge from God, a sign of his divine wrath at the policies of a non-believer.”

Obviously, this story went far beyond just Mo and his family. It became part of the stage-setting for perhaps the most consequential election in a generation.

…

Though no one would say it openly, at least, not immediately, the president’s diagnosis and subsequent decision not to seek re-election also held massive political ramifications.

The Democrats, who felt confident of their ability to rally around Mo for four more years, were suddenly thrown into disarray. Who would they nominate to carry the banner for them in 1980? Could they still count on “incumbent’s advantage” when they no longer had an incumbent?

To some, Vice President Lloyd Bentsen seemed the obvious answer. If the incumbent president cannot run again, then isn’t his number two the next best thing? Bentsen did have a number of things going for him, from the outset. As the incumbent VP, he was intimately tied to the administration in the eyes of the public. Even if many of Udall’s accomplishments had been “too liberal” for moderate Bentsen, he could keep quiet on his prior opposition to them and simply ride the wave of their popularity. Though he waited a few months before forming an exploratory committee, out of respect for his boss, the vice president did indeed intend to run. He’d meant to do so in 1984, after all. What was four years earlier?

But Bentsen immediately had more than his share of detractors as well.

For one thing, Bentsen, though well-spoken and skilled at debate, was not particularly charismatic. With Former Vice President Ronald Reagan’s nomination by the Republicans all but certain to many, a potential Reagan-Bentsen match-up seemed dubious, at best. Bentsen had beaten Reagan on the debate stage four years prior. “You’re no Harry Truman” was still a household line in politics. But one debate did not and would not win an entire campaign. Simply put, Bentsen did not excite people the way that Udall did, or the way that many Democrats feared Reagan would.

This presented a conundrum: if not Bentsen, then who?

Alternatives presented themselves largely depending on which wing of the Democratic Party one consulted. Communitarians throughout the south immediately pitched Senator Jimmy Carter of Georgia. Carter, then a former governor, had only narrowly decided against a bid in 1976. With his own folksy charm, 1980 really felt like it could be his year. There was New York Governor Hugh Carey, the former Congressman from Brooklyn, widely hailed across the country as “the man who saved New York” for his efforts at resolving NYC’s budgetary crisis. Carey held a certain panache for the more Old School, New Deal liberals in the party, though it wasn’t clear he even wanted the job. A widower, Carey seemed content to continue to govern his home state in Albany. Then there was Jerry Brown, “Governor Moonbeam” of California, who had taken over from James Roosevelt after his retirement in 1974. Brown was eccentric, and youthful, only 42 in 1980, but his caustic personality and unpredictable nature made him an unlikely pick.

Other names: Arkansas Senator Dale Bumpers (“every northerner’s favorite southerner”); Florida Governor Reubin Askew; floated around for a while. Several of these would ultimately make a bid for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1980. They were joined by one more name. The big one. The heavy hitter. The one who everyone in America waited to hear from, the moment that the clamor from President Udall’s announcement died down.

Senator Robert F. Kennedy, of New York.

Fifty-four years old in 1979, Bobby had been a Senator from New York for the past nine years. Of course, before that, he had famously worked in his brother’s White House for all eight years of his administration, first as Attorney General, then later as Secretary of Defense. Jack Kennedy’s chief advisor, closest confidant, and his little brother, Bobby Kennedy was, despite his relative youth, arguably the “elder statesman” for his generation of Democratic politicians.

Passionate, ruthless, and absolutely tough-as-nails, “the first Irish Puritan” had been forced to stand aside in 1976 due to the lingering fallout from the Hoover Affair. Kennedy’s reputation had taken a hit, especially within the Black community, for his prior authorization of wiretaps on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Stokley Carmichael, and other civil rights leaders. In the years since, Senator Kennedy had apologized for this decision, calling it, “the greatest mistake” of his career. He’d also worked tirelessly to restore his connections with African-Americans, Hispanic-Americans, and other minority communities, championing their causes in the Senate, in the streets, and on television screens and radio airwaves.

On a personal level, Kennedy had all but given up his presidential aspirations after 1976. Mo Udall championed many of the same causes he did. Thus, RFK was happy to support him from the sidelines, as Mo had once supported Jack. But Udall’s decision to step down sparked a fire in Bobby’s stomach. He recalled the conversation he’d had with Jack in the Oval Office, all those years before.

“One day, it’ll be you here, Bobby. It’ll be your call.”

Shortly after Udall’s announcement of his diagnosis, Senator Kennedy called the president to wish him the best, and to express his sympathy. About a month later, he spoke to his beloved wife, Ethel, about the prospect of him running in 1980. She gave him her blessing, as did an ailing Jack.

“It’s your time now.” The former President Kennedy said, simply, from his wheelchair. “Give ‘em Hell.”

Bobby hugged his brother and promised that he would.

Next Time on Blue Skies in Camelot: More Foreign Affairs!Author's Note: So... I know that I have some explaining to do.

...

I know that up to this point, pretty much all of the foreshadowing pointed toward President Udall running for a second term. I even started this "Act" of the story with a quote, supposedly from Udall's second nomination acceptance speech at the 1980 convention. I want to take a moment to apologize if you feel that you've been hoodwinked. This was not always my plan. But after much careful consideration, and writing two versions of this chapter, I eventually deleted the other and decided to go with this one.

IOTL, Mo was diagnosed with Parkinson's in 1979 as well. Part of his rationale for not running for president again in 1984 was because his disease had progressed, even by that time. He continued to serve in Congress until 1991, by which time his condition had deteriorated and he no longer felt he was able to serve. Given this information, I initially planned to have Mo announce his condition to the public, and forge on, hoping to explain how his diagnosis did not prevent him from being an effective commander in chief. However, the more I thought about getting to this point in the Timeline, the more I began to have second thoughts.

For one thing, serving as President of the United States is orders of magnitude more demanding than serving as a member of the House of Representatives. Even if Udall's campaign schedule could be lightened at all, he would still be subjected to the a gauntlet of seemingly endless policy meetings, tense negotiations over policy both domestic and foreign, and security briefings. Should there be some kind of military crisis, he would need to be physically fit and sound of mind for hours, potentially days on end, running on very little sleep. As mentioned in the chapter, there are also the political considerations.

Would it be possible for Udall to explain his condition to the public? To make them see that, for the time being, he is still more than capable of serving as their president? Possibly. He is charismatic. The people generally like him. But then again, even if he could, it would expend a great deal of his political capital just getting them to believe in him. To have faith that the disease won't progress too rapidly. I know that both IOTL and ITTL, Udall was a very career-focused person. He often prioritized his time in office over time with his wives and kids. IOTL, Ella Udall tragically died by suicide in the late 1980s, a decision that was possibly made in part because she did chafe against the limelight of political campaigns. ITTL, with the white hot media spotlight on them, I could see Udall deciding that the right thing, the honorable thing to do, would be to stand aside and find another path for his public advocacy.

I will cover all of this in more detail moving forward. As per OTL, Mo Udall will live into the 1990s. I plan on having him become a very public advocate not just for Parkinson's awareness, but for all neurodegenerative disorders, raising money and campaigning for a cure.

I hope you all will still enjoy this TL despite this change in direction. I repeat that this decision was made after long, careful consideration.

As always, thanks for reading.

- President_Lincoln

Share: