Yeah, it's a tricky thing to say the least. Also here's what I was thinking for some of the cast. For John Van de Kamp, the District Attorney, I was thinking maybe Tommy Lee Jones. Not sure who would play the two prosecutors but I feel like they would need to have the feel of Jack McCoy and Claire Kincaid like. For Susan Gailey, Samantha's mother I was thinking Paget Brewster. The rest I kept thinking about but I don't exactly know. This type of movie I would say would be a very hard movie to cast for example, I would have no idea who would play Polanski. Or Nicholson and Anjelica Huston, same with Monroe. Any thoughts?Not sure. Middling at the least. Enough to drive home the horror of what happened

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Blue Skies in Camelot (Continued): An Alternate 80s and Beyond

- Thread starter President_Lincoln

- Start date

Thank you for your reply, Mr. President. I am glad that you agreed on the need for educational reformsSo long as charter schools do not take away funding or attention from the public school system, then I think that they can be a useful alternative for students. I also agree that we definitely need more investment in trade and vocational schools! In general, I hope that this timeline sees more respect for workers of all different "collars". I feel like labor solidarity will be more of a thing here.

Charter school: a publicly funded independent school established by teachers, parents, or community groups under the terms of a charter with a local or national authority.

Gotcha. Thank you for the clarification.Thank you for your reply, Mr. President. I am glad that you agreed on the need for educational reforms, although I wanted to clarify that when I say charter schools, I mean the following:

To quote from Chapter 141 about the downballots from 1980.My gut tells me RFK is going to be replaced by a Kennedy family friend or maybe someone like John Lindsay.

New York

Elizabeth Holtzman (D) - Appointed by Governor Hugh Carey to fill President-Elect Robert Kennedy’s seat.

Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D) - Defeated Al D'amato to succeed retiring incumbent Clark. D Hold.

Chapter 147

Chapter 147 - Hit Me With Your Best Shot - RFK’s First 100 Days in Office

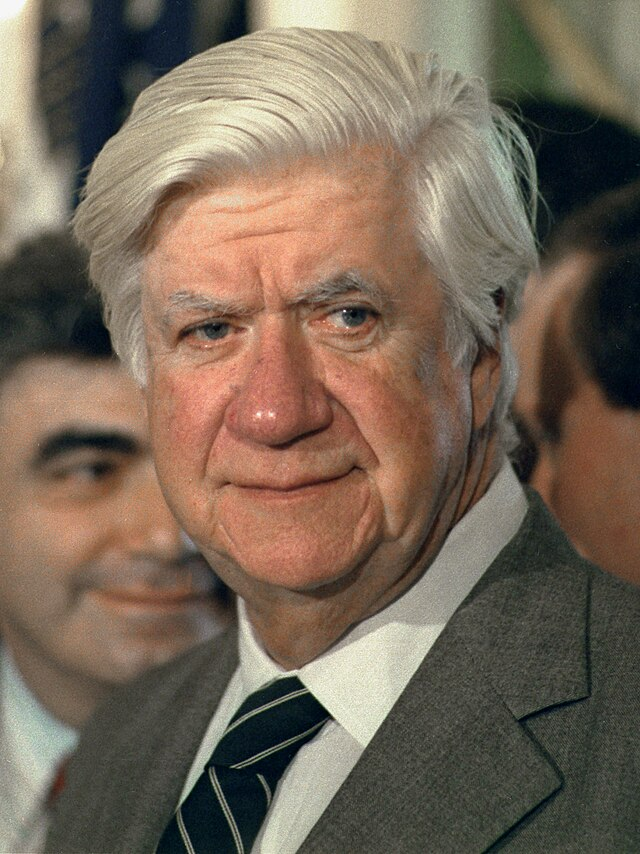

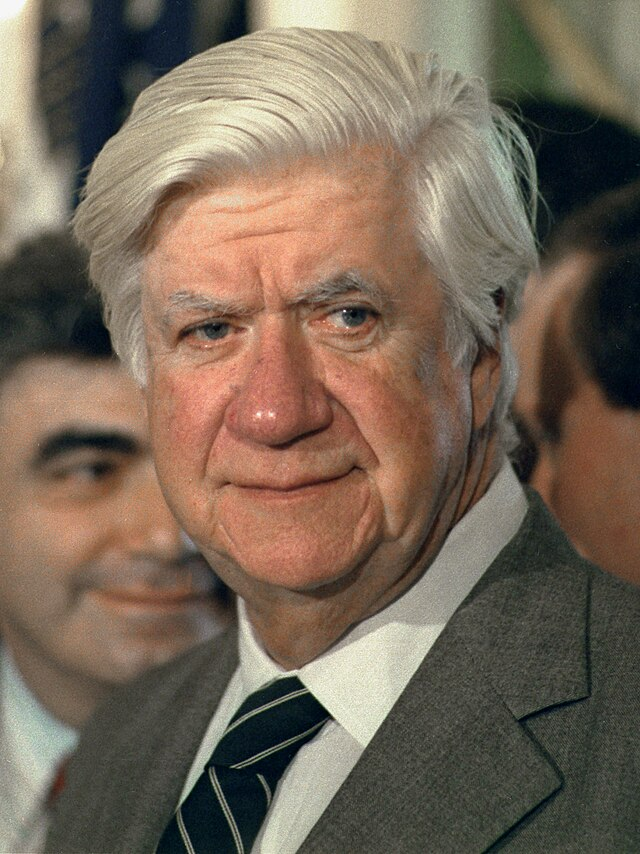

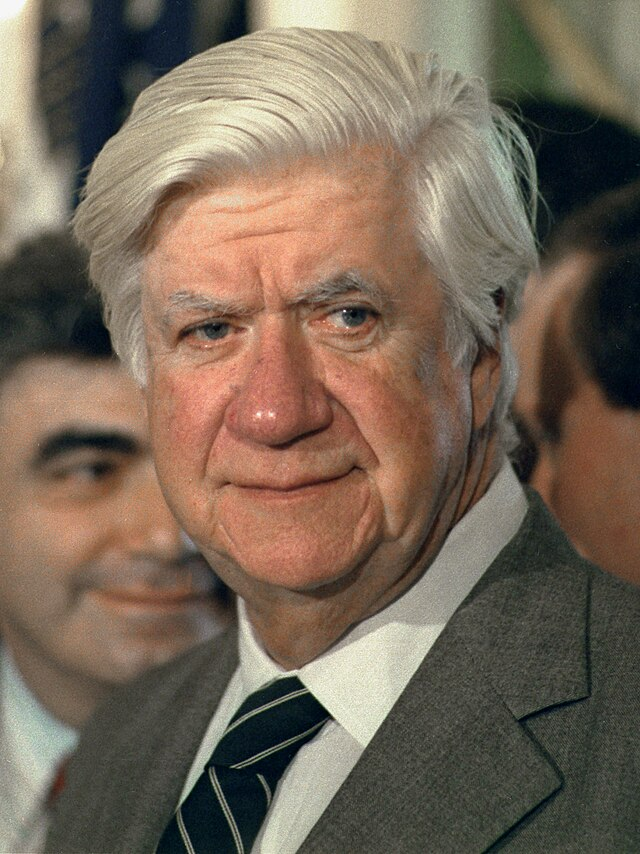

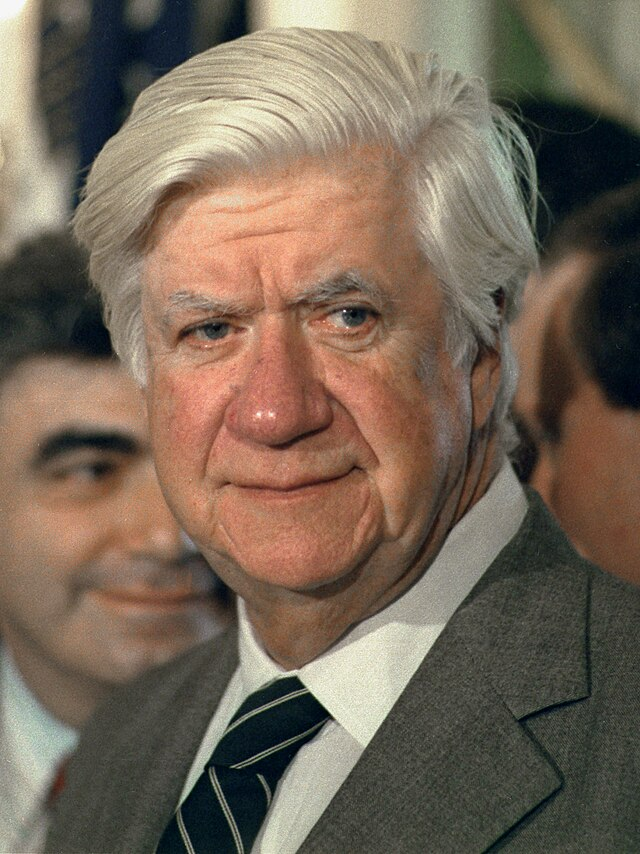

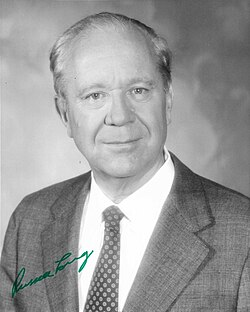

Above: President Robert F. Kennedy makes a speech calling on Congress to pass the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 (ERTA) or the “Long-Ullman Tax Cut” (left); the US Capitol, decorated for Kennedy’s inauguration (center); House Speaker Tip O’Neill (D - MA) (right).“You come on with it, come on

You don't fight fair

But that's okay, see if I care

Knock me down, it's all in vain

I get right back on my feet again

Hit me with your best shot

Why don't you hit me with your best shot

Hit me with your best shot

Fire away” - “Hit Me With Your Best Shot” by Pat Benatar

“Tax reform means, ‘Don’t tax you, don’t tax me. Tax that fellow behind the tree.’” - Russell B. Long

“A good lesson in keeping your perspective is: Take your job seriously but don’t take yourself seriously.” - Tip O’Neill

The first one hundred days of an incoming President’s first term are usually referred to as the “honeymoon” period. Both Congress and the press traditionally give the new Commander in Chief a chance to settle into the White House, and do their best to be friendly to them. This often means setting politics aside, at least for the time being, and fostering a sense of cooperation. Bob Kennedy sought to use this to his advantage.

Of all the promises that Kennedy had made in the campaign, he felt that his tax reform and economic recovery bill was not only the most popular, but the most urgently needed.

For the last two fiscal years, the federal government had been running a steadily growing deficit. Largely, this was the result of high costs associated with new spending under the Udall administration (Universal Medicare, AKA “MoCare” chief among them), combined with reduced tax receipts as a result of stagflation. With the rainy day fund depleted, President Kennedy sought to right the country’s fiscal ship and get the economy running again.

To do this, he wanted to sign a tax reform bill that accomplished two key objectives: first, expand the tax base by abolishing certain credits and tax shelters, and closing many loopholes for corporations and the wealthy; second, lower individual rates on middle and lower income households and individuals. Inspired by a suggestion from Treasury Secretary James Tobin, Kennedy’s proposal also included a tax on foreign exchange transactions, designed to reduce speculation in international currency markets. The proposed bill also included a one time “windfall tax” on the massive glut of profits the fossil fuel industry had enjoyed in the wake of the 1979-1980 oil shock. This would, ideally, turn the federal deficit into a surplus, provide working class Americans with much needed tax relief, and help to stimulate the economy by incentivizing consumption.

As his elder brother had once remarked on tax cuts: “a rising tide lifts all boats”.

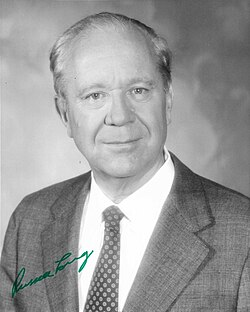

During his first formal meeting with Congressional leadership in the Roosevelt Room in the West Wing of the White House on Wednesday, February 4th, 1981, President Kennedy laid out his wish-list on tax reform. The proposals were met with the expected enthusiasm from his younger brother, Senate Majority Whip Ted Kennedy and House Speaker Tip O’Neill, but less so from the Senate Majority Leader, Russell B. Long.

62 years old in February of 1981, Senator Long was, arguably, the most competent and talented legislator in the Senate at that time. Having served in the Upper Chamber since the 1940s, Long had accumulated a great deal of power and prestige. In addition to serving as Majority Leader since Mike Mansfield’s retirement in 1977, Long also sat as Chairman on the powerful Finance Committee. This is where President Kennedy’s tax bill, should it be proposed, would originate once it reached the Senate.

Though Long - the son of the famous “Kingfish”, Huey Long - was sympathetic to progressive policies that would help the working class, he was also, above all else, a pragmatist. Long was acutely aware that, having lost a seat in November, his majority required either airtight unity or (even better) support from moderate Republicans in order to pass a tax reform like this. There was also the matter of getting it through the House in the first place.

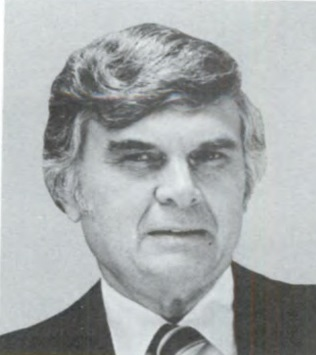

Al Ullman (D - OR) was the Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee; he was much more moderate than both the President and the Senate Majority Leader. What was more, Ullman had some very specific ideas he wanted included in any tax reform bill that he’d release to the floor for debate.

After narrowly winning reelection in a tight race in 1980, Ullman wanted more cuts than were present in President Kennedy’s proposal. Namely, he wanted reductions - even slight ones - on the top income brackets. That way, he could tell his (increasingly conservative) constituents back in Oregon that he had helped to author “across the board” cuts. He also strongly desired the creation of a federal “value-added tax” also known as a consumption tax, to help close the deficit. This policy would, essentially, charge a small tax at every stage of a product’s supply chain. Ultimately, however, if businesses collected the VAT at the final point of sale, they could receive rebates on taxes paid at previous steps of the manufacturing process. Ullman argued that many other developed nations - including Japan and most of Western Europe - had already adopted some version of the VAT, and that it could prove useful to the United States as well.

In 1980, Ullman ordered the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to conduct an economic study on implementing a VAT in the United States. At the time, the CBO concluded that a modest federal VAT could add as much as $100 billion in annual revenue. Adjusted to 2022 dollars, that amount comes out to roughly $300 billion. In other words, just about enough to close the budget deficit. This would, in Ullman’s mind, allow other federal monies to pay for other expenditures, such as the increases in healthcare and defense spending that President Kennedy was sure to call for.

As Long expected, the President balked at this idea.

Because the working class spent a much higher percentage of their incomes on consumption, they were, consequently, disproportionately affected by a consumption tax (such as VAT). This sort of tax could also lead to higher prices for consumers, which again, would disproportionately affect the poor. Kennedy, pugnacious and combative as ever, put up resistance to any such tax being added to the proposal.

“I didn’t get elected by the working people of this country just to turn around and stiff them.” Kennedy explained, coolly. “I think this idea is regressive. I think it punishes people for living paycheck to paycheck.”

Long sighed, then gave his own perspective.

“Mr. President, I see where you’re coming from. Remember, my daddy had his ‘Share Our Wealth’ program during the Depression. Six years ago, I worked with President Bush to create the Earned Income Tax Credit. If there’s a cause that I believe in, it’s helping working folks.”

Long shot a glance over to O’Neill, who nodded.

“But I’ve been in this city a long time. And if there’s anything I’ve learned, it’s that you don’t cut your nose just to spite your face. You can’t afford to.”

“What we’ve got here, is the opportunity to do something that no President has even attempted since Franklin D Roosevelt: reform the tax code. You and I both agree that that system ought to and must be progressive. The people that benefit the most from the system ought to pay their fair share. That being said, you’ve got to remember that crafting legislation is a heck of a lot different than your job. Everybody wants to have a hand in it.”

“If you tell Ullman that there’s no way you’d let a value-added tax into the bill, he might take that personally. Might even resent you for it. He might lock your bill up in committee, whether on principle, or just to spite you.”

Long gestured to the other parts of Kennedy’s proposal, printed out on reams of paper on the conference table before them.

“On the whole, this bill is a win for working people. A big win.”

“I say, let Ullman make his adjustments. His amendments. We’ll take out the top bracket reductions in the Senate version. They’ll come out for good in reconciliation. Call it a compromise. Our Republican friends will like the VAT. It’ll make them feel like we’re spreading the burden around a bit. We keep up the estate tax, capital gains, corporate tax. You order the Fed to reduce interest rates later this year, demand explodes. Economy booms. Big tax receipts. Bye-bye deficit. Everybody wins.”

All eyes in the room went to the President. Kennedy frowned.

“Except for the people who have to pay the most VAT.”

The air seemed to get sucked from the room. For a moment, it seemed that all these negotiations were leading nowhere, fast.

“Bobby,” Ted Kennedy cut in.

The President’s eyes went to his brother.

Ted continued. “Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good.”

Reluctantly, the President sighed.

“Fine. But tell Ullman I want at least $75 billion for the gas and oil windfall tax. If he suggests any further reductions, pull him in for a one on one immediately. Agreed, gentlemen?”

Nods all around. The legislators got to work.

…

Above: The Hilton Hotel in Washington, D.C. (left); the seal of the AFL-CIO (right).

Above: The Hilton Hotel in Washington, D.C. (left); the seal of the AFL-CIO (right).

While early versions of what would come to be called the Economic Recovery and Tax Act of 1981 (ERTA) or, more popularly, “the Long-Ullman Tax Cut”, were being written and prepared for introduction to the House Ways and Means Committee, President Kennedy arranged for a number of meetings with various civil rights and labor groups. Natural allies of his administration, Kennedy wanted to make clear his commitment to delivering on the promises he had made to them on the campaign trail as well.

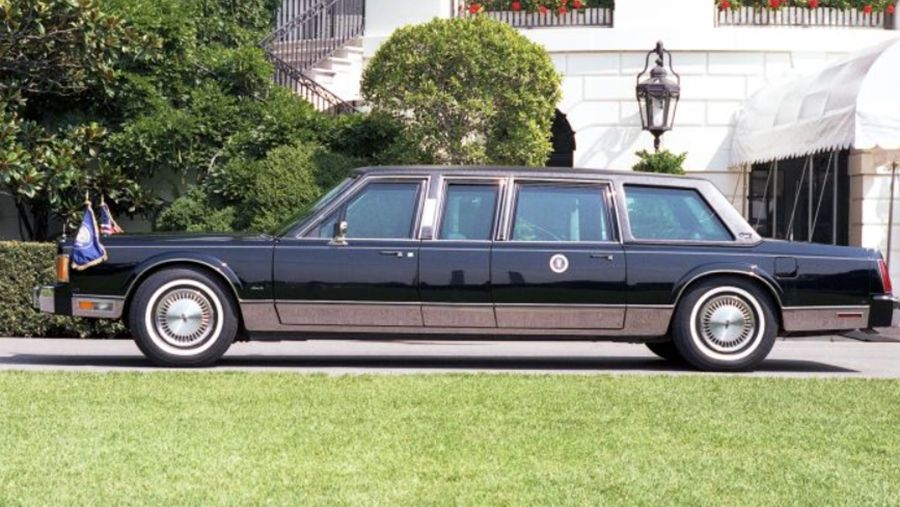

One such meeting - with the AFL-CIO - was scheduled for Monday, March 30th, 1981 at the Hilton Hotel in Washington. Kennedy entered the hotel through the “President’s walk”, an enclosed passageway that opened onto Florida Avenue. This passageway had been constructed in 1973 in the aftermath of the assassination of President George Romney. Unique among the hotels in Washington for this feature, the Hilton was thus considered one of the most secure in the capital by the Secret Service.

Kennedy entered the hotel at approximately 1:45 PM, waving to a crowd of news media and citizens. The Secret Service had required him to wear a bulletproof vest for some events, and Kennedy was indeed wearing one for the speech.

At the meeting, President Kennedy attended a luncheon with the union’s leadership and delivered an address. In that speech, Kennedy vowed to continue his fight for “equitable treatment for the working people of this country”. No doubt, his tax reform proposal was at the forefront of his mind that day.

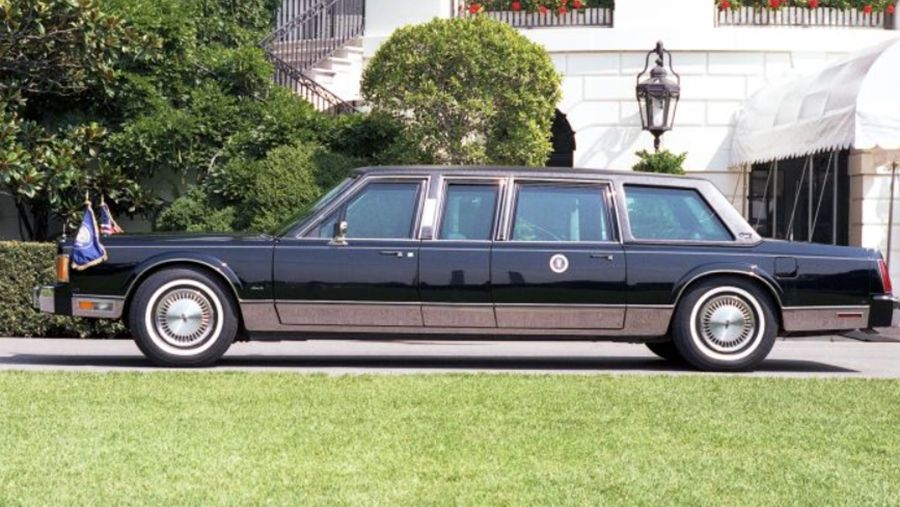

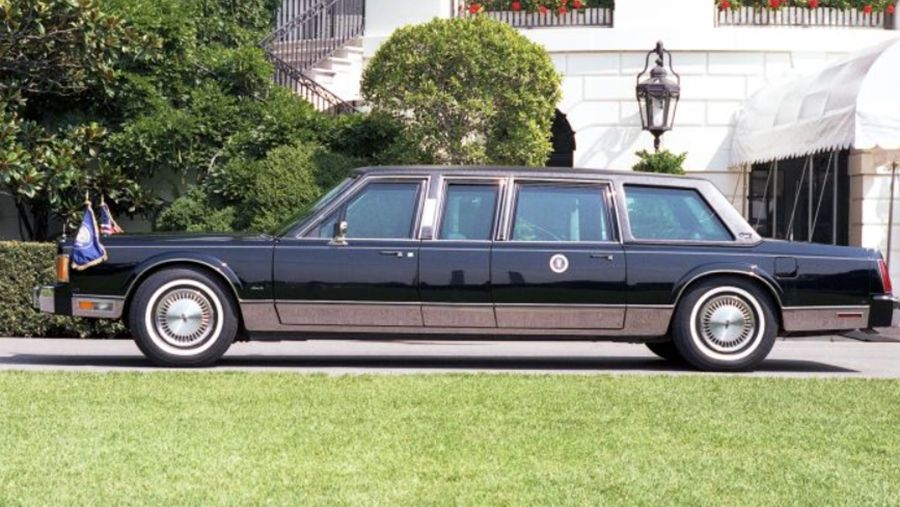

At 2:29 PM, Kennedy exited the way that he had entered, once again through the President’s Walk. At the end of the walk, reporters waited with cameras and tape recorders, eager to try and ask the President a question before he sped off to his next scheduled event. He once again waved and made his way toward his waiting limousine.

Little did he suspect that someone was waiting within the crowd of admirers and well-wishers. Someone who wished him harm.

The Secret Service had extensively screened those attending the president's speech, but greatly erred by allowing an unscreened group to stand within 15 ft of him, behind a rope line. By procedure, the agency uses multiple layers of protection; local police in the outer layer briefly check people, Secret Service agents in the middle layer check for weapons, and more agents form the inner layer immediately around the president. This man had penetrated the first two layers.

As several hundred people applauded Kennedy, the president unexpectedly passed directly in front of the man who meant him harm. Reporters standing behind a rope barricade twenty feet away asked questions.

As Tia Brown of the Associated Press shouted “Mr. President-”, the man, believing he would never get a better chance, pressed suddenly forward. Before anyone knew what was happening, the man produced a snub-nosed Charter Arms revolver - a so-called “.38 special” - and fired five rounds at the president in rapid succession from about nine or ten feet away.

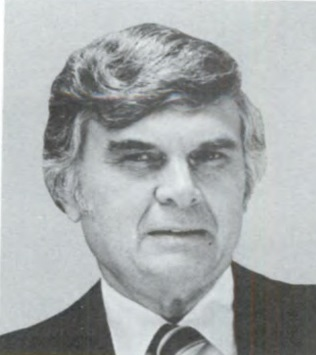

The first round hit White House Communications Director Frank Mankiewicz, a longtime Kennedy staff member and family friend, who had served Kennedy since he first entered the Senate ten years earlier. The shot hit Mankiewicz in the head above his left eye; because the round was a hollow point bullet, it expanded on impact, transferring most of its energy into Mankiewicz’ brain. He was killed on impact. He was fifty-five years old.

A Washington, D.C. police officer named Daniel Mills recognized the sound as a gunshot. Turning his head to try and identify the shooter, he was then struck by the second shot in the back of his neck. Falling on top of Mankiewicz, Mills screamed, “I’m hit! I’m hit!”

The assailant now had a clear shot at President Kennedy.

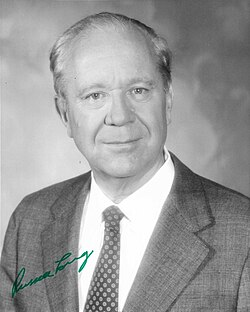

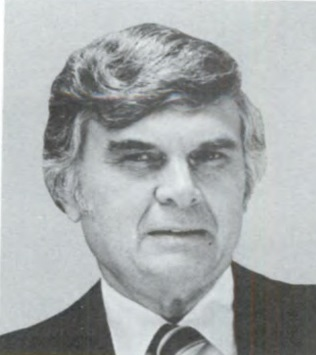

Above: Frank Manciewicz, White House Communications Director, who was murdered on March 30th, 1981.

Thankfully, Frederico Fasulo, a labor official from Newark, New Jersey who happened to be standing nearby, saw the shooter fire the first two shots. Acting quickly, Fasulo charged the man, hit him hard on the head, and began to wrestle him to the ground, trying to separate the pistol from his hand.

Upon hearing the first shots, Special Agent in Charge Remington Nash grabbed President Kennedy by the shoulders and dove with him toward the open rear door of the limousine. Another agent trailed behind Nash and the president and assisted in throwing both of them into the car.

The would-be assassin managed to squeeze off a third shot, which overshot the president, instead hitting the window of a news van parked nearby.

As Fasulo continued to struggle with the perpetrator, Secret Service agents swarmed the area. Two more shots rang out. Before he could fire the sixth, the assailant had been pinned by Fasulo, Secret Service agents, and DC police. The president was thrown across the floor of the limousine, whereupon he was then dogpiled by three agents, as their training had taught them to do.

After the Secret Service first announced “shots fired” over its radio network at 2:29 PM, President Kennedy - codenamed “Chevalier” - was taken away by agents in the limousine (“steed”). No one knew whether Kennedy had been shot.

Agent Nash checked the president’s midsection. His hands came away wet with blood.

“Go to GWU Hospital!” He shouted at the driver. Then, into his radio, trying to keep his voice calm, he dispatched. “Chevalier has been shot. Repeat - Chevalier has been shot. Steed inbound to hospital.”

From beneath Nash, the president managed to wheeze, “Ethel… Make sure she’s safe… Ethel…”

…

Above: First Lady Ethel Kennedy puts her hand up to a reporter’s camera as she rushes to her husband’s side at George Washington University Hospital, where he was being prepped for emergency surgery.

At the time of the attempt on her husband’s life, First Lady Ethel Kennedy was meeting with a group of activists who were interested in dredging and otherwise cleaning the Potomac River and its environs.

At 2:31 PM, when the call that “Chevalier has been shot” first came over their radios, Mrs. Kennedy’s Secret Service detail abruptly cut off the activist who was speaking, took the first lady’s arm and informed her, politely, but firmly, that they needed to leave. Mrs. Kennedy apologized profusely and followed her agents. In the hallway outside the conference center, they informed her of her husband’s situation. She felt a pit form in her stomach.

No. She thought, with a growing panic. Bobby, no!

Dodging the press on her way out of the conference center, the first lady and her security team leapt into their limousine and bounded off for the GW hospital. On the ride over, Ethel could not help but see hers and Bobby’s life together flash before her eyes.

Before she ever knew Robert Francis Kennedy, Ethel Skakel was born in Chicago to businessman George Skakel and his former secretary Ann Brannack on April 11th, 1928. Tragically, her parents were both killed in a 1955 plane crash. The third of four Skakel daughters and the sixth of seven children, Ethel could relate to Bobby’s feeling growing up of being (just about) “the runt of the litter”.

Raised Catholic in Greenwich, Connecticut, Ethel went on to begin her college education at Manhattanville College in September of 1945, where she was a classmate of her future sister-in-law Jean Kennedy. Ethel first met Jean’s brother, Bobby, during a ski trip to Mont Tremblant Resort in Quebec in December 1945. During this trip, Bobby began dating Ethel's older sister Patricia, but after that relationship ended he began to date Ethel. She campaigned for Jack Kennedy in his 1946 campaign for the United States Congress in Boston, and she wrote her college thesis on his book Why England Slept. She received a bachelor's degree from Manhattanville in 1949.

Robert Kennedy and Ethel Skakel became engaged in February of 1950 and were married on June 17th of that year, at St. Mary's Catholic Church in Greenwich. While her husband worked for the federal government in investigatory roles for the US Senate as a counsel (first under Joseph McCarthy, and later, much more favorably under Estes Kefauver investigating corrupt labor union leadership), Ethel became a dedicated mother and homemaker for the first of what would ultimately be their eleven children (a near record for a first family). The Kennedys purchased Hickory Hill, an estate in McLean, Virginia, from Jack and Jackie, which would serve as RFK’s primary residence throughout his time in Washington, including his eventual roles in his brother’s administration, and as a US Senator from New York.

Above: President Robert Kennedy and First Lady Ethel Kennedy on their wedding day.

Theirs was a genuinely happy and loving marriage, a rarity indeed for that time. But it was one rooted in their shared faith in God and their common beliefs about family, justice, and the importance of individuals to stand up and fight for human rights. While Jack and Ted became somewhat infamous for their infidelities, Bobby never wavered, remaining faithful to Ethel throughout their lives together.

That isn’t to say that their marriage was not without its challenges.

Raising eleven children would be a Herculean feat for any couple. But with Bobby’s attention ever fixed toward his political career, Ethel handled much of the discipline and decision-making herself. Whenever one of their kids ran into trouble at school, or their grades slipped, or any of the other myriad situations that arise while growing up, Ethel had to handle them herself. Bobby was always burying himself in work, whether as attorney general, secretary of defense, senator, or finally, president. But Ethel Kennedy was a strong woman and a very good mother. Her children loved her and knew that she and their father both loved them in return. Bobby and Ethel encouraged their kids to develop both a strong sense of ethics and a deeply competitive nature, similar to what Joe and Rose Kennedy had instilled in Bobby.

…

On March 30th, 1981, Ethel raced to the hospital.

Upon arrival, she was rushed inside and greeted by the hospital’s head surgeon, who briefed her on her husband’s condition. The president had been shot twice: once in the chest and once just below his stomach. Because the bullets were hollow points, the first was stopped by the vest he wore, and did not penetrate his skin. The second, however, landed a few inches shy of the bottom of the vest and “mushroomed” upon entering the president’s side, lodging itself just below his left hip.

It was too early to tell exactly how much internal damage had been done. The president reported difficulty controlling or moving his left leg, which might imply a severed nerve. X-rays and CT scans were necessary to know for sure, and to know if any bones had been broken.

More immediately, the bullet appeared to have nicked, if not ruptured several blood vessels. The president was bleeding profusely. The Secret Service agents managed to slow the bleeding somewhat with a jury rigged bandage in the limousine on the drive over to the hospital, but it was a temporary fix, and had not stopped the bleeding entirely by any means. Kennedy would need to be prepped for immediate surgery, if the doctors were going to be able to save his life. The head surgeon was honest with the first lady. The situation seemed grim.

Having been briefed, Ethel was allowed into the emergency room to see him for a few moments before the operation began. She gasped when she saw him. His head rested on a stack of pillows as he lay in the hospital bed. Already, a team of more doctors, nurses, and technicians buzzed about, hooking him up to an IV and a number of machines.

Ethel ran to his side and cradled his head in her arms.

“Oh, Bobby…”

“Shh…” The president spoke very softly, hardly above a whisper. It was clear that he was in a great deal of pain. “I don’t have much time.” He looked up into her eyes. “I love you, honey. And the kids. I love them. No matter what happens, tell them for me.”

“I will. I’ll pray for you. We all will.”

And so they did.

…

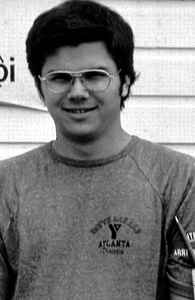

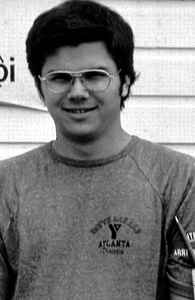

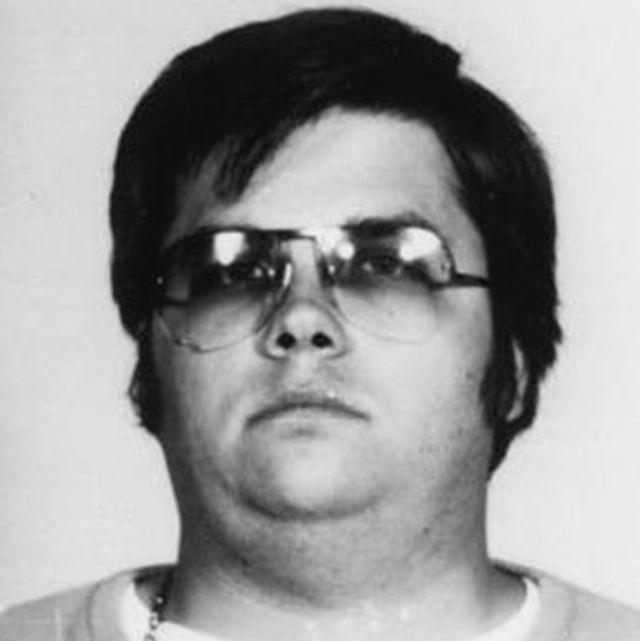

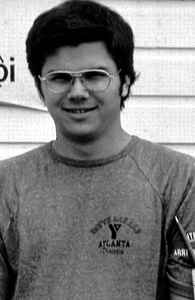

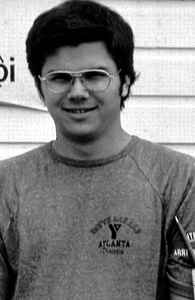

Above: A teenaged Mark David Chapman, circa the early 1970s.

Above: A teenaged Mark David Chapman, circa the early 1970s.

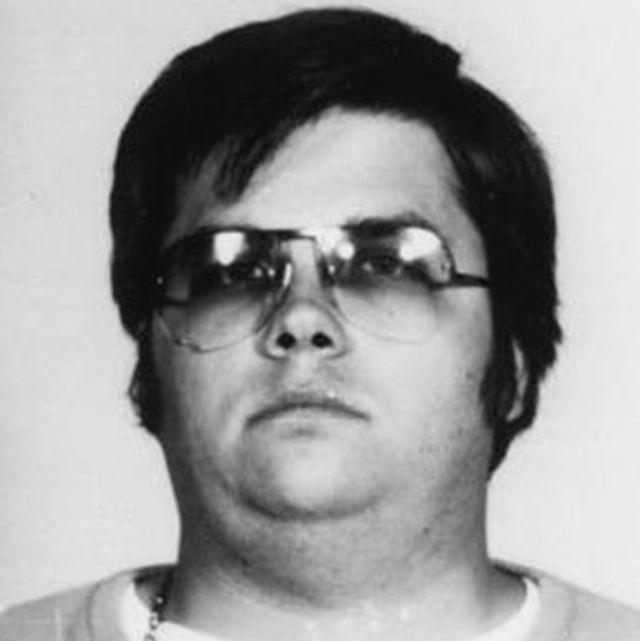

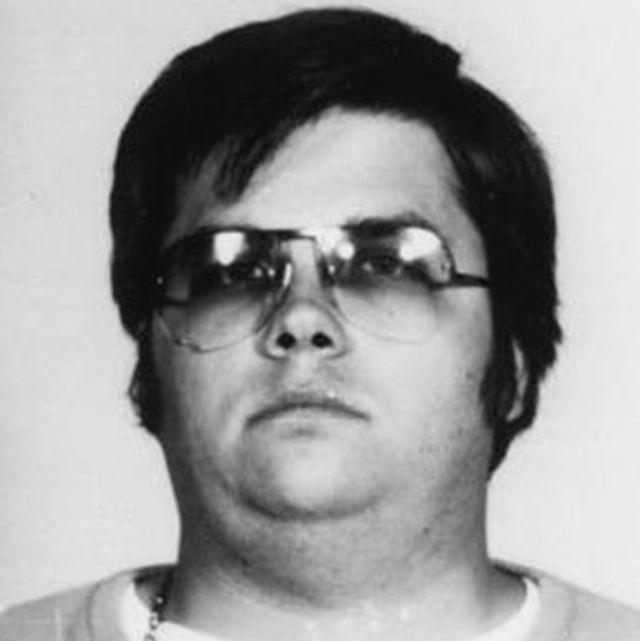

The man who murdered Frank Mankiewicz, who severely maimed Officer Mills, and who shot President Robert F. Kennedy was 25 year old Mark David Chapman.

Chapman was born on May 10th, 1955 in Fort Worth, Texas. His father, David, was U.S. Air Force staff sergeant, while his mother, Diane, was a nurse. He also had a younger sister, Susan, who was born in 1962. Growing up, Chapman was terrified of his father, whom Chapman later claimed was physically abusive toward his mother and distant toward Chapman and his sister. Perhaps to try and cope with his feelings of powerlessness, young Chapman created elaborate fantasies for himself to revel in. In these fantasies, Chapman was an omnipotent, God-like figure who ruled over imaginary “little people” who lived in his walls. Owing to his father’s position in the Air Force, the family moved around a lot. This made making friends or forming lasting social connections of any kind difficult for the Chapman kids. By the time he was 14, Mark was taking drugs and skipping classes. While the family was living in Atlanta, Georgia, Chapman ran away and lived on the streets for two weeks before returning home. Due in part to his meek nature, and part to his lack of athletic ability and overweight appearance, Chapman was a frequent target for bullies.

As a teenager in the early 1970s, Chapman became a born-again Christian, handed out pamphlets after school, and volunteered at youth group events. He met his first girlfriend, Elsie Jones, and became a counselor at a YMCA summer camp. He was very popular with the children, who nicknamed him "Rico" (after the protagonist of the Robert Heinlein novel Starship Troopers, a favorite of Chapman’s) and was promoted to assistant director after winning an award for Outstanding Counselor. To those that knew him at the time, it seemed that in his faith, Chapman had finally found a cause toward which he could devote himself.

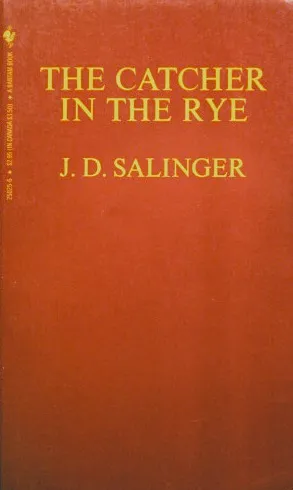

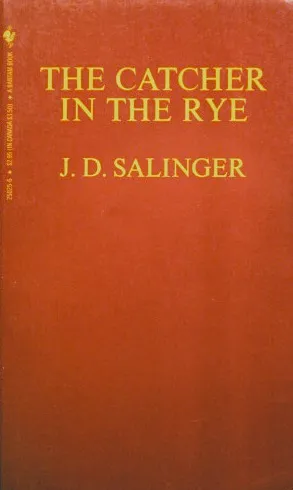

Around that same time, Chapman read J. D. Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye on the recommendation of a friend. The novel eventually took on great personal significance for him, to the extent he reportedly wished to model his life after its protagonist, Holden Caulfield.

After graduating from high school, Chapman moved for a time to Chicago and played guitar in churches and Christian night spots. He worked successfully for World Vision with Cambodian refugees at a resettlement camp at Fort Chaffee in Arkansas, after a brief visit to Lebanon for the same work. He was named an area coordinator and a key aide to program director David Moore, who later said Chapman cared deeply for the children and worked hard. Chapman accompanied Moore to meetings with government officials, and President George Bush shook his hand in a photo that would, given later context, become infamous.

Chapman enrolled as a student at Covenant College, an evangelical Presbyterian liberal arts college in Lookout Mountain, Georgia. However, Chapman fell behind in his studies and became racked with guilt over having an affair with a fellow student. He started having suicidal thoughts and began to feel like a failure. He dropped out of college after just one semester, and his girlfriend - Elsie - broke off their relationship soon after. Chapman returned to work at the resettlement camp but left after an argument with a supervisor.

In 1977, Chapman moved to Hawaii, where he attempted suicide by carbon monoxide asphyxiation. He connected a hose to his car's exhaust pipe, but the hose melted and the attempt failed. A psychiatrist admitted Chapman to Castle Memorial Hospital for clinical depression. Upon his release from the ward, he began working at the hospital as a janitor. Later that year, his parents divorced and his mother joined him in Hawaii.

The following year, Chapman embarked on a six-week trip around the world. The vacation was partly inspired by the film and novel Around the World in 80 Days. During this trip, he visited Tokyo, Seoul, Hong Kong, Singapore, Bangkok, New Delhi, Beirut, Geneva, London, Paris, and Dublin. He began a relationship with his travel agent, a Japanese American woman named Gloria Abe, whom he later married on June 2, 1979. Chapman got a job at Castle Memorial Hospital as a printer, working alone rather than with other staff and patients. He was then fired by the hospital and later rehired; following an argument with a nurse he finally quit. After this, Chapman took a job as a night security guard at a high end apartment complex and began drinking heavily to cope with his depression.

In the depths of his depression, he developed a series of obsessions. These were often esoteric and vaguely spiritual in nature. They included the artwork of Francisco Goya, The Catcher in the Rye; popular music (which he felt was “sinful” and “corrupting”); and finally, far right politics.

Sometime in the late 1970s, seeking friendship and camaraderie, Chapman accepted the invitation of a fellow born-again evangelical and became a member of the John Birch Society.

Originally founded by Robert W. Welch, Jr. in 1958, the “Birchers” as they were known, were ultraconservative, far-right, and virulently bigoted in their beliefs. The Society, which had once been instrumental to the founding of the American Conservative Party in 1968, propagated conspiracy theories. Most of these centered on the idea of a “cabal” of secret communists that had “infiltrated” American society and were attempting to bring down the United States from within via “corrupting influences”. In truth, most of these conspiracies, which targeted liberals of course, but even Republican politicians like Dwight D. Eisenhower and George Romney, were also virulently antisemitic in nature. Even William F. Buckley, intellectual head of the conservative movement, felt that the Birchers were, in a word, “nuts”. Buckley and his allies did all they could to relegate “Birchism” to the “fringes” of conservative politics. As a result, throughout the 1970s, the Society’s influence diminished significantly, especially after the collapse of the ACP.

Despite this, by 1979, when Chapman joined, the Society still boasted some 15,000 - 20,000 members nationwide. In their pamphlets and newsletters, the Birchers ranted and raved about so-called “Jewish influence” and “cultural marxism” in both mainstream political parties. They pointed to then-President Mo Udall as an “obvious communist”, and lamented that all three major candidates for 1980 - John Anderson, Robert Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan - were no better. Though they did not call for violence outright, the screeds made it clear that “electoralism”, as they called it, would not solve America’s “Jewish problem.”

As he consumed these conspiracy theories, Chapman’s already fragile mental state only continued to deteriorate. According to Chapman’s statements in his later parole hearings, it was around this time that he developed what he called his “hit list”. This was a list of potential targets for his wrath. He singled out figures that he believed represented the worst of “cultural marxist influence” in America. Names on the list apparently included: John Lennon and Paul McCartney of the Beatles; talk show host Johnny Carson; actresses Elizabeth Taylor and Marilyn Monroe; actor Marlon Brando; Hawaii governor George Ariyoshi; and finally, the Kennedys. In his mind, the Kennedys - ultra-wealthy, coastal elitist liberals - represented the pinnacle of what was “wrong” with America. He eventually settled on one of them as his chosen target.

At first, he claimed to consider targeting former President John F. Kennedy and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy. But after Robert Kennedy was elected president in November of 1980, Chapman’s mind was made up.

He later confessed to being “envious” of Kennedy and the media attention that he received, both during the campaign and after it concluded. Chapman attended Kennedy’s inauguration in January of 1981, intending to shoot him during the parade. But he decided against this due to elevated security throughout the event. Dejected, Chapman briefly stayed in Atlanta, Georgia to purchase hollow point bullets, which he felt were more likely to successfully kill the president, should they hit. He also feverishly read and re-read the Freund Report, which chronicled Arthur Bremer’s assassination of President Romney in March of 1972.

After tracking the president’s movements throughout February and March, Chapman settled on the March 30th date as probably his best chance to enact his plan. Thus, the attempt went forward. He managed to shoot the President of the United States.

Next Time on Blue Skies in Camelot: RFK Fights for His Life

Last edited:

You serious left us off from there? You can't kill Bobby, with how far he's come. How far we've come as readers, this can't be how it ends for him. Other than that good chapter. I guess the only sucky thing about this is that we have to wait a whole week to find out whether the man that the future of the country of depends on lives. I am gonna be so impatient for next week. But I'll shall wait.Chapter 147 - Hit Me With Your Best Shot - RFK’s First 100 Days in OfficeAbove: President Robert F. Kennedy makes a speech calling on Congress to pass the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 (ERTA) or the “Long-Ullman Tax Cut” (left); the US Capitol, decorated for Kennedy’s inauguration (center); House Speaker Tip O’Neill (D - MA) (right).

“You come on with it, come on

You don't fight fair

But that's okay, see if I care

Knock me down, it's all in vain

I get right back on my feet again

Hit me with your best shot

Why don't you hit me with your best shot

Hit me with your best shot

Fire away” - “Hit Me With Your Best Shot” by Pat Benatar

“Tax reform means, ‘Don’t tax you, don’t tax me. Tax that fellow behind the tree.’” - Russell B. Long

“A good lesson in keeping your perspective is: Take your job seriously but don’t take yourself seriously.” - Tip O’Neill

The first one hundred days of an incoming President’s first term are usually referred to as the “honeymoon” period. Both Congress and the press traditionally give the new Commander in Chief a chance to settle into the White House, and do their best to be friendly to them. This often means setting politics aside, at least for the time being, and fostering a sense of cooperation. Bob Kennedy sought to use this to his advantage.

Of all the promises that Kennedy had made in the campaign, he felt that his tax reform and economic recovery bill was not only the most popular, but the most urgently needed.

For the last two fiscal years, the federal government had been running a steadily growing deficit. Largely, this was the result of high costs associated with new spending under the Udall administration (Universal Medicare, AKA “MoCare” chief among them), combined with reduced tax receipts as a result of stagflation. With the rainy day fund depleted, President Kennedy sought to right the country’s fiscal ship and get the economy running again.

To do this, he wanted to sign a tax reform bill that accomplished two key objectives: first, expand the tax base by abolishing certain credits and tax shelters, and closing many loopholes for corporations and the wealthy; second, lower individual rates on middle and lower income households and individuals. Inspired by a suggestion from Treasury Secretary James Tobin, Kennedy’s proposal also included a tax on foreign exchange transactions, designed to reduce speculation in international currency markets. The proposed bill also included a one time “windfall tax” on the massive glut of profits the fossil fuel industry had enjoyed in the wake of the 1979-1980 oil shock. This would, ideally, turn the federal deficit into a surplus, provide working class Americans with much needed tax relief, and help to stimulate the economy by incentivizing consumption.

As his elder brother had once remarked on tax cuts: “a rising tide lifts all boats”.

During his first formal meeting with Congressional leadership in the Roosevelt Room in the West Wing of the White House on Wednesday, February 4th, 1981, President Kennedy laid out his wish-list on tax reform. The proposals were met with the expected enthusiasm from his younger brother, Senate Majority Whip Ted Kennedy and House Speaker Tip O’Neill, but less so from the Senate Majority Leader, Russell B. Long.

62 years old in February of 1981, Senator Long was, arguably, the most competent and talented legislator in the Senate at that time. Having served in the Upper Chamber since the 1940s, Long had accumulated a great deal of power and prestige. In addition to serving as Majority Leader since Mike Mansfield’s retirement in 1977, Long also sat as Chairman on the powerful Finance Committee. This is where President Kennedy’s tax bill, should it be proposed, would originate once it reached the Senate.

Though Long - the son of the famous “Kingfish”, Huey Long - was sympathetic to progressive policies that would help the working class, he was also, above all else, a pragmatist. Long was acutely aware that, having lost a seat in November, his majority required either airtight unity or (even better) support from moderate Republicans in order to pass a tax reform like this. There was also the matter of getting it through the House in the first place.

Al Ullman (D - OR) was the Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee; he was much more moderate than both the President and the Senate Majority Leader. What was more, Ullman had some very specific ideas he wanted included in any tax reform bill that he’d release to the floor for debate.

After narrowly winning reelection in a tight race in 1980, Ullman wanted more cuts than were present in President Kennedy’s proposal. Namely, he wanted reductions - even slight ones - on the top income brackets. That way, he could tell his (increasingly conservative) constituents back in Oregon that he had helped to author “across the board” cuts. He also strongly desired the creation of a federal “value-added tax” also known as a consumption tax, to help close the deficit. This policy would, essentially, charge a small tax at every stage of a product’s supply chain. Ultimately, however, if businesses collected the VAT at the final point of sale, they could receive rebates on taxes paid at previous steps of the manufacturing process. Ullman argued that many other developed nations - including Japan and most of Western Europe - had already adopted some version of the VAT, and that it could prove useful to the United States as well.

In 1980, Ullman ordered the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to conduct an economic study on implementing a VAT in the United States. At the time, the CBO concluded that a modest federal VAT could add as much as $100 billion in annual revenue. Adjusted to 2022 dollars, that amount comes out to roughly $300 billion. In other words, just about enough to close the budget deficit. This would, in Ullman’s mind, allow other federal monies to pay for other expenditures, such as the increases in healthcare and defense spending that President Kennedy was sure to call for.

As Long expected, the President balked at this idea.

Because the working class spent a much higher percentage of their incomes on consumption, they were, consequently, disproportionately affected by a consumption tax (such as VAT). This sort of tax could also lead to higher prices for consumers, which again, would disproportionately affect the poor. Kennedy, pugnacious and combative as ever, put up resistance to any such tax being added to the proposal.

“I didn’t get elected by the working people of this country just to turn around and stiff them.” Kennedy explained, coolly. “I think this idea is regressive. I think it punishes people for living paycheck to paycheck.”

Long sighed, then gave his own perspective.

“Mr. President, I see where you’re coming from. Remember, my daddy had his ‘Share Our Wealth’ program during the Depression. Six years ago, I worked with President Bush to create the Earned Income Tax Credit. If there’s a cause that I believe in, it’s helping working folks.”

Long shot a glance over to O’Neill, who nodded.

“But I’ve been in this city a long time. And if there’s anything I’ve learned, it’s that you don’t cut your nose just to spite your face. You can’t afford to.”

“What we’ve got here, is the opportunity to do something that no President has even attempted since Franklin D Roosevelt: reform the tax code. You and I both agree that that system ought to and must be progressive. The people that benefit the most from the system ought to pay their fair share. That being said, you’ve got to remember that crafting legislation is a heck of a lot different than your job. Everybody wants to have a hand in it.”

“If you tell Ullman that there’s no way you’d let a value-added tax into the bill, he might take that personally. Might even resent you for it. He might lock your bill up in committee, whether on principle, or just to spite you.”

Long gestured to the other parts of Kennedy’s proposal, printed out on reams of paper on the conference table before them.

“On the whole, this bill is a win for working people. A big win.”

“I say, let Ullman make his adjustments. His amendments. We’ll take out the top bracket reductions in the Senate version. They’ll come out for good in reconciliation. Call it a compromise. Our Republican friends will like the VAT. It’ll make them feel like we’re spreading the burden around a bit. We keep up the estate tax, capital gains, corporate tax. You order the Fed to reduce interest rates later this year, demand explodes. Economy booms. Big tax receipts. Bye-bye deficit. Everybody wins.”

All eyes in the room went to the President. Kennedy frowned.

“Except for the people who have to pay the most VAT.”

The air seemed to get sucked from the room. For a moment, it seemed that all these negotiations were leading nowhere, fast.

“Bobby,” Ted Kennedy cut in.

The President’s eyes went to his brother.

Ted continued. “Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good.”

Reluctantly, the President sighed.

“Fine. But tell Ullman I want at least $75 billion for the gas and oil windfall tax. If he suggests any further reductions, pull him in for a one on one immediately. Agreed, gentlemen?”

Nods all around. The legislators got to work.

…

Above: The Hilton Hotel in Washington, D.C. (left); the seal of the AFL-CIO (right).

While early versions of what would come to be called the Economic Recovery and Tax Act of 1981 (ERTA) or, more popularly, “the Long-Ullman Tax Cut”, were being written and prepared for introduction to the House Ways and Means Committee, President Kennedy arranged for a number of meetings with various civil rights and labor groups. Natural allies of his administration, Kennedy wanted to make clear his commitment to delivering on the promises he had made to them on the campaign trail as well.

One such meeting - with the AFL-CIO - was scheduled for Monday, March 30th, 1981 at the Hilton Hotel in Washington. Kennedy entered the hotel through the “President’s walk”, an enclosed passageway that opened onto Florida Avenue. This passageway had been constructed in 1973 in the aftermath of the assassination of President George Romney. Unique among the hotels in Washington for this feature, the Hilton was thus considered one of the most secure in the capital by the Secret Service.

Kennedy entered the hotel at approximately 1:45 PM, waving to a crowd of news media and citizens. The Secret Service had required him to wear a bulletproof vest for some events, and Kennedy was indeed wearing one for the speech.

At the meeting, President Kennedy attended a luncheon with the union’s leadership and delivered an address. In that speech, Kennedy vowed to continue his fight for “equitable treatment for the working people of this country”. No doubt, his tax reform proposal was at the forefront of his mind that day.

At 2:29 PM, Kennedy exited the way that he had entered, once again through the President’s Walk. At the end of the walk, reporters waited with cameras and tape recorders, eager to try and ask the President a question before he sped off to his next scheduled event. He once again waved and made his way toward his waiting limousine.

Little did he suspect that someone was waiting within the crowd of admirers and well-wishers. Someone who wished him harm.

The Secret Service had extensively screened those attending the president's speech, but greatly erred by allowing an unscreened group to stand within 15 ft of him, behind a rope line. By procedure, the agency uses multiple layers of protection; local police in the outer layer briefly check people, Secret Service agents in the middle layer check for weapons, and more agents form the inner layer immediately around the president. This man had penetrated the first two layers.

As several hundred people applauded Kennedy, the president unexpectedly passed directly in front of the man who meant him harm. Reporters standing behind a rope barricade twenty feet away asked questions.

As Tia Brown of the Associated Press shouted “Mr. President-”, the man, believing he would never get a better chance, pressed suddenly forward. Before anyone knew what was happening, the man produced a snub-nosed Charter Arms revolver - a so-called “.38 special” - and fired five rounds at the president in rapid succession from about nine or ten feet away.

The first round hit White House Communications Director Frank Mankiewicz, a longtime Kennedy staff member and family friend, who had served Kennedy since he first entered the Senate ten years earlier. The shot hit Mankiewicz in the head above his left eye; because the round was a hollow point bullet, it expanded on impact, transferring most of its energy into Mankiewicz’ brain. He was killed on impact. He was fifty-five years old.

A Washington, D.C. police officer named Daniel Mills recognized the sound as a gunshot. Turning his head to try and identify the shooter, he was then struck by the second shot in the back of his neck. Falling on top of Mankiewicz, Mills screamed, “I’m hit! I’m hit!”

The assailant now had a clear shot at President Kennedy.

Above: Frank Manciewicz, White House Communications Director, who was murdered on March 30th, 1981.

Thankfully, Frederico Fasulo, a labor official from Newark, New Jersey who happened to be standing nearby, saw the shooter fire the first two shots. Acting quickly, Fasulo charged the man, hit him hard on the head, and began to wrestle him to the ground, trying to separate the pistol from his hand.

Upon hearing the first shots, Special Agent in Charge Remington Nash grabbed President Kennedy by the shoulders and dove with him toward the open rear door of the limousine. Another agent trailed behind Nash and the president and assisted in throwing both of them into the car.

The would-be assassin managed to squeeze off a third shot, which overshot the president, instead hitting the window of a news van parked nearby.

As Fasulo continued to struggle with the perpetrator, Secret Service agents swarmed the area. Two more shots rang out. Before he could fire the sixth, the assailant had been pinned by Fasulo, Secret Service agents, and DC police. The president was thrown across the floor of the limousine, whereupon he was then dogpiled by three agents, as their training had taught them to do.

After the Secret Service first announced “shots fired” over its radio network at 2:29 PM, President Kennedy - codenamed “Chevalier” - was taken away by agents in the limousine (“steed”). No one knew whether Kennedy had been shot.

Agent Nash checked the president’s midsection. His hands came away wet with blood.

“Go to GWU Hospital!” He shouted at the driver. Then, into his radio, trying to keep his voice calm, he dispatched. “Chevalier has been shot. Repeat - Chevalier has been shot. Steed inbound to hospital.”

From beneath Nash, the president managed to wheeze, “Ethel… Make sure she’s safe… Ethel…”

…

Above: First Lady Ethel Kennedy puts her hand up to a reporter’s camera as she rushes to her husband’s side at George Washington University Hospital, where he was being prepped for emergency surgery.

At the time of the attempt on her husband’s life, First Lady Ethel Kennedy was meeting with a group of activists who were interested in dredging and otherwise cleaning the Potomac River and its environs.

At 2:31 PM, when the call that “Chevalier has been shot” first came over their radios, Mrs. Kennedy’s Secret Service detail abruptly cut off the activist who was speaking, took the first lady’s arm and informed her, politely, but firmly, that they needed to leave. Mrs. Kennedy apologized profusely and followed her agents. In the hallway outside the conference center, they informed her of her husband’s situation. She felt a pit form in her stomach.

No. She thought, with a growing panic. Bobby, no!

Dodging the press on her way out of the conference center, the first lady and her security team leapt into their limousine and bounded off for the GW hospital. On the ride over, Ethel could not help but see hers and Bobby’s life together flash before her eyes.

Before she ever knew Robert Francis Kennedy, Ethel Skakel was born in Chicago to businessman George Skakel and his former secretary Ann Brannack on April 11th, 1928. Tragically, her parents were both killed in a 1955 plane crash. The third of four Skakel daughters and the sixth of seven children, Ethel could relate to Bobby’s feeling growing up of being (just about) “the runt of the litter”.

Raised Catholic in Greenwich, Connecticut, Ethel went on to begin her college education at Manhattanville College in September of 1945, where she was a classmate of her future sister-in-law Jean Kennedy. Ethel first met Jean’s brother, Bobby, during a ski trip to Mont Tremblant Resort in Quebec in December 1945. During this trip, Bobby began dating Ethel's older sister Patricia, but after that relationship ended he began to date Ethel. She campaigned for Jack Kennedy in his 1946 campaign for the United States Congress in Boston, and she wrote her college thesis on his book Why England Slept. She received a bachelor's degree from Manhattanville in 1949.

Robert Kennedy and Ethel Skakel became engaged in February of 1950 and were married on June 17th of that year, at St. Mary's Catholic Church in Greenwich. While her husband worked for the federal government in investigatory roles for the US Senate as a counsel (first under Joseph McCarthy, and later, much more favorably under Estes Kefauver investigating corrupt labor union leadership), Ethel became a dedicated mother and homemaker for the first of what would ultimately be their eleven children (a near record for a first family). The Kennedys purchased Hickory Hill, an estate in McLean, Virginia, from Jack and Jackie, which would serve as RFK’s primary residence throughout his time in Washington, including his eventual roles in his brother’s administration, and as a US Senator from New York.

Above: President Robert Kennedy and First Lady Ethel Kennedy on their wedding day.

Theirs was a genuinely happy and loving marriage, a rarity indeed for that time. But it was one rooted in their shared faith in God and their common beliefs about family, justice, and the importance of individuals to stand up and fight for human rights. While Jack and Ted became somewhat infamous for their infidelities, Bobby never wavered, remaining faithful to Ethel throughout their lives together.

That isn’t to say that their marriage was not without its challenges.

Raising eleven children would be a Herculean feat for any couple. But with Bobby’s attention ever fixed toward his political career, Ethel handled much of the discipline and decision-making herself. Whenever one of their kids ran into trouble at school, or their grades slipped, or any of the other myriad situations that arise while growing up, Ethel had to handle them herself. Bobby was always burying himself in work, whether as attorney general, secretary of defense, senator, or finally, president. But Ethel Kennedy was a strong woman and a very good mother. Her children loved her and knew that she and their father both loved them in return. Bobby and Ethel encouraged their kids to develop both a strong sense of ethics and a deeply competitive nature, similar to what Joe and Rose Kennedy had instilled in Bobby.

…

On March 30th, 1981, Ethel raced to the hospital.

Upon arrival, she was rushed inside and greeted by the hospital’s head surgeon, who briefed her on her husband’s condition. The president had been shot twice: once in the chest and once just below his stomach. Because the bullets were hollow points, the first was stopped by the vest he wore, and did not penetrate his skin. The second, however, landed a few inches shy of the bottom of the vest and “mushroomed” upon entering the president’s side, lodging itself just below his left hip.

It was too early to tell exactly how much internal damage had been done. The president reported difficulty controlling or moving his left leg, which might imply a severed nerve. X-rays and CT scans were necessary to know for sure, and to know if any bones had been broken.

More immediately, the bullet appeared to have nicked, if not ruptured several blood vessels. The president was bleeding profusely. The Secret Service agents managed to slow the bleeding somewhat with a jury rigged bandage in the limousine on the drive over to the hospital, but it was a temporary fix, and had not stopped the bleeding entirely by any means. Kennedy would need to be prepped for immediate surgery, if the doctors were going to be able to save his life. The head surgeon was honest with the first lady. The situation seemed grim.

Having been briefed, Ethel was allowed into the emergency room to see him for a few moments before the operation began. She gasped when she saw him. His head rested on a stack of pillows as he lay in the hospital bed. Already, a team of more doctors, nurses, and technicians buzzed about, hooking him up to an IV and a number of machines.

Ethel ran to his side and cradled his head in her arms.

“Oh, Bobby…”

“Shh…” The president spoke very softly, hardly above a whisper. It was clear that he was in a great deal of pain. “I don’t have much time.” He looked up into her eyes. “I love you, honey. And the kids. I love them. No matter what happens, tell them for me.”

“I will. I’ll pray for you. We all will.”

And so they did.

…

Above: A teenaged Mark David Chapman, circa the early 1970s.

The man who murdered Frank Mankiewicz, who severely maimed Officer Mills, and who shot President Robert F. Kennedy was 35 year old Mark David Chapman.

Chapman was born on May 10th, 1955 in Fort Worth, Texas. His father, David, was U.S. Air Force staff sergeant, while his mother, Diane, was a nurse. He also had a younger sister, Susan, who was born in 1962. Growing up, Chapman was terrified of his father, whom Chapman later claimed was physically abusive toward his mother and distant toward Chapman and his sister. Perhaps to try and cope with his feelings of powerlessness, young Chapman created elaborate fantasies for himself to revel in. In these fantasies, Chapman was an omnipotent, God-like figure who ruled over imaginary “little people” who lived in his walls. Owing to his father’s position in the Air Force, the family moved around a lot. This made making friends or forming lasting social connections of any kind difficult for the Chapman kids. By the time he was 14, Mark was taking drugs and skipping classes. While the family was living in Atlanta, Georgia, Chapman ran away and lived on the streets for two weeks before returning home. Due in part to his meek nature, and part to his lack of athletic ability and overweight appearance, Chapman was a frequent target for bullies.

As a teenager in the early 1970s, Chapman became a born-again Christian, handed out pamphlets after school, and volunteered at youth group events. He met his first girlfriend, Elsie Jones, and became a counselor at a YMCA summer camp. He was very popular with the children, who nicknamed him "Rico" (after the protagonist of the Robert Heinlein novel Starship Troopers, a favorite of Chapman’s) and was promoted to assistant director after winning an award for Outstanding Counselor. To those that knew him at the time, it seemed that in his faith, Chapman had finally found a cause toward which he could devote himself.

Around that same time, Chapman read J. D. Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye on the recommendation of a friend. The novel eventually took on great personal significance for him, to the extent he reportedly wished to model his life after its protagonist, Holden Caulfield.

After graduating from high school, Chapman moved for a time to Chicago and played guitar in churches and Christian night spots. He worked successfully for World Vision with Cambodian refugees at a resettlement camp at Fort Chaffee in Arkansas, after a brief visit to Lebanon for the same work. He was named an area coordinator and a key aide to program director David Moore, who later said Chapman cared deeply for the children and worked hard. Chapman accompanied Moore to meetings with government officials, and President George Bush shook his hand in a photo that would, given later context, become infamous.

Chapman enrolled as a student at Covenant College, an evangelical Presbyterian liberal arts college in Lookout Mountain, Georgia. However, Chapman fell behind in his studies and became racked with guilt over having an affair with a fellow student. He started having suicidal thoughts and began to feel like a failure. He dropped out of college after just one semester, and his girlfriend - Elsie - broke off their relationship soon after. Chapman returned to work at the resettlement camp but left after an argument with a supervisor.

In 1977, Chapman moved to Hawaii, where he attempted suicide by carbon monoxide asphyxiation. He connected a hose to his car's exhaust pipe, but the hose melted and the attempt failed. A psychiatrist admitted Chapman to Castle Memorial Hospital for clinical depression. Upon his release from the ward, he began working at the hospital as a janitor. Later that year, his parents divorced and his mother joined him in Hawaii.

The following year, Chapman embarked on a six-week trip around the world. The vacation was partly inspired by the film and novel Around the World in 80 Days. During this trip, he visited Tokyo, Seoul, Hong Kong, Singapore, Bangkok, New Delhi, Beirut, Geneva, London, Paris, and Dublin. He began a relationship with his travel agent, a Japanese American woman named Gloria Abe, whom he later married on June 2, 1979. Chapman got a job at Castle Memorial Hospital as a printer, working alone rather than with other staff and patients. He was then fired by the hospital and later rehired; following an argument with a nurse he finally quit. After this, Chapman took a job as a night security guard at a high end apartment complex and began drinking heavily to cope with his depression.

In the depths of his depression, he developed a series of obsessions. These were often esoteric and vaguely spiritual in nature. They included the artwork of Francisco Goya, The Catcher in the Rye; popular music (which he felt was “sinful” and “corrupting”); and finally, far right politics.

Above: Logo for the antisemitic, far right organization known as the John Birch Society (left); The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger (center); Saturn Devouring His Son by Francisco Goya (right).

Sometime in the late 1970s, seeking friendship and camaraderie, Chapman accepted the invitation of a fellow born-again evangelical and became a member of the John Birch Society.

Originally founded by Robert W. Welch, Jr. in 1958, the “Birchers” as they were known, were ultraconservative, far-right, and virulently bigoted in their beliefs. The Society, which had once been instrumental to the founding of the American Conservative Party in 1968, propagated conspiracy theories. Most of these centered on the idea of a “cabal” of secret communists that had “infiltrated” American society and were attempting to bring down the United States from within via “corrupting influences”. In truth, most of these conspiracies, which targeted liberals of course, but even Republican politicians like Dwight D. Eisenhower and George Romney, were also virulently antisemitic in nature. Even William F. Buckley, intellectual head of the conservative movement, felt that the Birchers were, in a word, “nuts”. Buckley and his allies did all they could to relegate “Birchism” to the “fringes” of conservative politics. As a result, throughout the 1970s, the Society’s influence diminished significantly, especially after the collapse of the ACP.

Despite this, by 1979, when Chapman joined, the Society still boasted some 15,000 - 20,000 members nationwide. In their pamphlets and newsletters, the Birchers ranted and raved about so-called “Jewish influence” and “cultural marxism” in both mainstream political parties. They pointed to then-President Mo Udall as an “obvious communist”, and lamented that all three major candidates for 1980 - John Anderson, Robert Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan - were no better. Though they did not call for violence outright, the screeds made it clear that “electoralism”, as they called it, would not solve America’s “Jewish problem.”

As he consumed these conspiracy theories, Chapman’s already fragile mental state only continued to deteriorate. According to Chapman’s statements in his later parole hearings, it was around this time that he developed what he called his “hit list”. This was a list of potential targets for his wrath. He singled out figures that he believed represented the worst of “cultural marxist influence” in America. Names on the list apparently included: John Lennon and Paul McCartney of the Beatles; talk show host Johnny Carson; actresses Elizabeth Taylor and Marilyn Monroe; actor Marlon Brando; Hawaii governor George Ariyoshi; and finally, the Kennedys. In his mind, the Kennedys - ultra-wealthy, coastal elitist liberals - represented the pinnacle of what was “wrong” with America. He eventually settled on one of them as his chosen target.

At first, he claimed to consider targeting former President John F. Kennedy and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy. But after Robert Kennedy was elected president in November of 1980, Chapman’s mind was made up.

He later confessed to being “envious” of Kennedy and the media attention that he received, both during the campaign and after it concluded. Chapman attended Kennedy’s inauguration in January of 1981, intending to shoot him during the parade. But he decided against this due to elevated security throughout the event. Dejected, Chapman briefly stayed in Atlanta, Georgia to purchase hollow point bullets, which he felt were more likely to successfully kill the president, should they hit. He also feverishly read and re-read the Freund Report, which chronicled Arthur Bremer’s assassination of President Romney in March of 1972.

After tracking the president’s movements throughout February and March, Chapman settled on the March 30th date as probably his best chance to enact his plan. Thus, the attempt went forward. He managed to shoot the President of the United States.

Above: President Robert F. Kennedy, after being shot. Secret services agents attempt to stabilize him until the limousine can reach the hospital (left); Mark David Chapman’s mugshot (right).

Next Time on Blue Skies in Camelot: RFK Fights for His Life

Thank you for your patience.You serious left us off from there? You can't kill Bobby, with how far he's come. How far we've come as readers, this can't be how it ends for him. Other than that good chapter. I guess the only sucky thing about this is that we have to wait a whole week to find out whether the man that the future of the country of depends on lives. I am gonna be so impatient for next week. But I'll shall wait.

The twists and turns in this update are astounding! I went from wondering how Bobby would pass his agenda to fearing for his life! I was confused about the assassin's identity given the obvious chosen date for the assassination and that John Hinckley Jr. is a musician ITTL, but then Chapman was name dropped. Oh boy am I now on the edge of my seat now more than ever. The idea that Chapman was going to target JFK if Bobby lost the 1980 election is also quite interesting. If Bobby dies it'll be the return of the Curse of Tippecanoe and if he lives the curse may be gone for good. Hopefully he pulls a Reagan and recoveres. Maybe he'll make a joke like Reagan did when he said to his doctors "I hope you're all Republicans" to which they replied with "Today, Mr. President we're all Republicans".Chapter 147 - Hit Me With Your Best Shot - RFK’s First 100 Days in OfficeAbove: President Robert F. Kennedy makes a speech calling on Congress to pass the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 (ERTA) or the “Long-Ullman Tax Cut” (left); the US Capitol, decorated for Kennedy’s inauguration (center); House Speaker Tip O’Neill (D - MA) (right).

“You come on with it, come on

You don't fight fair

But that's okay, see if I care

Knock me down, it's all in vain

I get right back on my feet again

Hit me with your best shot

Why don't you hit me with your best shot

Hit me with your best shot

Fire away” - “Hit Me With Your Best Shot” by Pat Benatar

“Tax reform means, ‘Don’t tax you, don’t tax me. Tax that fellow behind the tree.’” - Russell B. Long

“A good lesson in keeping your perspective is: Take your job seriously but don’t take yourself seriously.” - Tip O’Neill

The first one hundred days of an incoming President’s first term are usually referred to as the “honeymoon” period. Both Congress and the press traditionally give the new Commander in Chief a chance to settle into the White House, and do their best to be friendly to them. This often means setting politics aside, at least for the time being, and fostering a sense of cooperation. Bob Kennedy sought to use this to his advantage.

Of all the promises that Kennedy had made in the campaign, he felt that his tax reform and economic recovery bill was not only the most popular, but the most urgently needed.

For the last two fiscal years, the federal government had been running a steadily growing deficit. Largely, this was the result of high costs associated with new spending under the Udall administration (Universal Medicare, AKA “MoCare” chief among them), combined with reduced tax receipts as a result of stagflation. With the rainy day fund depleted, President Kennedy sought to right the country’s fiscal ship and get the economy running again.

To do this, he wanted to sign a tax reform bill that accomplished two key objectives: first, expand the tax base by abolishing certain credits and tax shelters, and closing many loopholes for corporations and the wealthy; second, lower individual rates on middle and lower income households and individuals. Inspired by a suggestion from Treasury Secretary James Tobin, Kennedy’s proposal also included a tax on foreign exchange transactions, designed to reduce speculation in international currency markets. The proposed bill also included a one time “windfall tax” on the massive glut of profits the fossil fuel industry had enjoyed in the wake of the 1979-1980 oil shock. This would, ideally, turn the federal deficit into a surplus, provide working class Americans with much needed tax relief, and help to stimulate the economy by incentivizing consumption.

As his elder brother had once remarked on tax cuts: “a rising tide lifts all boats”.

During his first formal meeting with Congressional leadership in the Roosevelt Room in the West Wing of the White House on Wednesday, February 4th, 1981, President Kennedy laid out his wish-list on tax reform. The proposals were met with the expected enthusiasm from his younger brother, Senate Majority Whip Ted Kennedy and House Speaker Tip O’Neill, but less so from the Senate Majority Leader, Russell B. Long.

62 years old in February of 1981, Senator Long was, arguably, the most competent and talented legislator in the Senate at that time. Having served in the Upper Chamber since the 1940s, Long had accumulated a great deal of power and prestige. In addition to serving as Majority Leader since Mike Mansfield’s retirement in 1977, Long also sat as Chairman on the powerful Finance Committee. This is where President Kennedy’s tax bill, should it be proposed, would originate once it reached the Senate.

Though Long - the son of the famous “Kingfish”, Huey Long - was sympathetic to progressive policies that would help the working class, he was also, above all else, a pragmatist. Long was acutely aware that, having lost a seat in November, his majority required either airtight unity or (even better) support from moderate Republicans in order to pass a tax reform like this. There was also the matter of getting it through the House in the first place.

Al Ullman (D - OR) was the Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee; he was much more moderate than both the President and the Senate Majority Leader. What was more, Ullman had some very specific ideas he wanted included in any tax reform bill that he’d release to the floor for debate.

After narrowly winning reelection in a tight race in 1980, Ullman wanted more cuts than were present in President Kennedy’s proposal. Namely, he wanted reductions - even slight ones - on the top income brackets. That way, he could tell his (increasingly conservative) constituents back in Oregon that he had helped to author “across the board” cuts. He also strongly desired the creation of a federal “value-added tax” also known as a consumption tax, to help close the deficit. This policy would, essentially, charge a small tax at every stage of a product’s supply chain. Ultimately, however, if businesses collected the VAT at the final point of sale, they could receive rebates on taxes paid at previous steps of the manufacturing process. Ullman argued that many other developed nations - including Japan and most of Western Europe - had already adopted some version of the VAT, and that it could prove useful to the United States as well.

In 1980, Ullman ordered the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to conduct an economic study on implementing a VAT in the United States. At the time, the CBO concluded that a modest federal VAT could add as much as $100 billion in annual revenue. Adjusted to 2022 dollars, that amount comes out to roughly $300 billion. In other words, just about enough to close the budget deficit. This would, in Ullman’s mind, allow other federal monies to pay for other expenditures, such as the increases in healthcare and defense spending that President Kennedy was sure to call for.

As Long expected, the President balked at this idea.

Because the working class spent a much higher percentage of their incomes on consumption, they were, consequently, disproportionately affected by a consumption tax (such as VAT). This sort of tax could also lead to higher prices for consumers, which again, would disproportionately affect the poor. Kennedy, pugnacious and combative as ever, put up resistance to any such tax being added to the proposal.

“I didn’t get elected by the working people of this country just to turn around and stiff them.” Kennedy explained, coolly. “I think this idea is regressive. I think it punishes people for living paycheck to paycheck.”

Long sighed, then gave his own perspective.

“Mr. President, I see where you’re coming from. Remember, my daddy had his ‘Share Our Wealth’ program during the Depression. Six years ago, I worked with President Bush to create the Earned Income Tax Credit. If there’s a cause that I believe in, it’s helping working folks.”

Long shot a glance over to O’Neill, who nodded.

“But I’ve been in this city a long time. And if there’s anything I’ve learned, it’s that you don’t cut your nose just to spite your face. You can’t afford to.”

“What we’ve got here, is the opportunity to do something that no President has even attempted since Franklin D Roosevelt: reform the tax code. You and I both agree that that system ought to and must be progressive. The people that benefit the most from the system ought to pay their fair share. That being said, you’ve got to remember that crafting legislation is a heck of a lot different than your job. Everybody wants to have a hand in it.”

“If you tell Ullman that there’s no way you’d let a value-added tax into the bill, he might take that personally. Might even resent you for it. He might lock your bill up in committee, whether on principle, or just to spite you.”

Long gestured to the other parts of Kennedy’s proposal, printed out on reams of paper on the conference table before them.

“On the whole, this bill is a win for working people. A big win.”

“I say, let Ullman make his adjustments. His amendments. We’ll take out the top bracket reductions in the Senate version. They’ll come out for good in reconciliation. Call it a compromise. Our Republican friends will like the VAT. It’ll make them feel like we’re spreading the burden around a bit. We keep up the estate tax, capital gains, corporate tax. You order the Fed to reduce interest rates later this year, demand explodes. Economy booms. Big tax receipts. Bye-bye deficit. Everybody wins.”

All eyes in the room went to the President. Kennedy frowned.

“Except for the people who have to pay the most VAT.”

The air seemed to get sucked from the room. For a moment, it seemed that all these negotiations were leading nowhere, fast.

“Bobby,” Ted Kennedy cut in.

The President’s eyes went to his brother.

Ted continued. “Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good.”

Reluctantly, the President sighed.

“Fine. But tell Ullman I want at least $75 billion for the gas and oil windfall tax. If he suggests any further reductions, pull him in for a one on one immediately. Agreed, gentlemen?”

Nods all around. The legislators got to work.

…

Above: The Hilton Hotel in Washington, D.C. (left); the seal of the AFL-CIO (right).

While early versions of what would come to be called the Economic Recovery and Tax Act of 1981 (ERTA) or, more popularly, “the Long-Ullman Tax Cut”, were being written and prepared for introduction to the House Ways and Means Committee, President Kennedy arranged for a number of meetings with various civil rights and labor groups. Natural allies of his administration, Kennedy wanted to make clear his commitment to delivering on the promises he had made to them on the campaign trail as well.

One such meeting - with the AFL-CIO - was scheduled for Monday, March 30th, 1981 at the Hilton Hotel in Washington. Kennedy entered the hotel through the “President’s walk”, an enclosed passageway that opened onto Florida Avenue. This passageway had been constructed in 1973 in the aftermath of the assassination of President George Romney. Unique among the hotels in Washington for this feature, the Hilton was thus considered one of the most secure in the capital by the Secret Service.

Kennedy entered the hotel at approximately 1:45 PM, waving to a crowd of news media and citizens. The Secret Service had required him to wear a bulletproof vest for some events, and Kennedy was indeed wearing one for the speech.

At the meeting, President Kennedy attended a luncheon with the union’s leadership and delivered an address. In that speech, Kennedy vowed to continue his fight for “equitable treatment for the working people of this country”. No doubt, his tax reform proposal was at the forefront of his mind that day.

At 2:29 PM, Kennedy exited the way that he had entered, once again through the President’s Walk. At the end of the walk, reporters waited with cameras and tape recorders, eager to try and ask the President a question before he sped off to his next scheduled event. He once again waved and made his way toward his waiting limousine.

Little did he suspect that someone was waiting within the crowd of admirers and well-wishers. Someone who wished him harm.

The Secret Service had extensively screened those attending the president's speech, but greatly erred by allowing an unscreened group to stand within 15 ft of him, behind a rope line. By procedure, the agency uses multiple layers of protection; local police in the outer layer briefly check people, Secret Service agents in the middle layer check for weapons, and more agents form the inner layer immediately around the president. This man had penetrated the first two layers.

As several hundred people applauded Kennedy, the president unexpectedly passed directly in front of the man who meant him harm. Reporters standing behind a rope barricade twenty feet away asked questions.

As Tia Brown of the Associated Press shouted “Mr. President-”, the man, believing he would never get a better chance, pressed suddenly forward. Before anyone knew what was happening, the man produced a snub-nosed Charter Arms revolver - a so-called “.38 special” - and fired five rounds at the president in rapid succession from about nine or ten feet away.

The first round hit White House Communications Director Frank Mankiewicz, a longtime Kennedy staff member and family friend, who had served Kennedy since he first entered the Senate ten years earlier. The shot hit Mankiewicz in the head above his left eye; because the round was a hollow point bullet, it expanded on impact, transferring most of its energy into Mankiewicz’ brain. He was killed on impact. He was fifty-five years old.

A Washington, D.C. police officer named Daniel Mills recognized the sound as a gunshot. Turning his head to try and identify the shooter, he was then struck by the second shot in the back of his neck. Falling on top of Mankiewicz, Mills screamed, “I’m hit! I’m hit!”

The assailant now had a clear shot at President Kennedy.

Above: Frank Manciewicz, White House Communications Director, who was murdered on March 30th, 1981.

Thankfully, Frederico Fasulo, a labor official from Newark, New Jersey who happened to be standing nearby, saw the shooter fire the first two shots. Acting quickly, Fasulo charged the man, hit him hard on the head, and began to wrestle him to the ground, trying to separate the pistol from his hand.